Encroaching Weeds: Alevtyna Kakhidze’s Stories of War

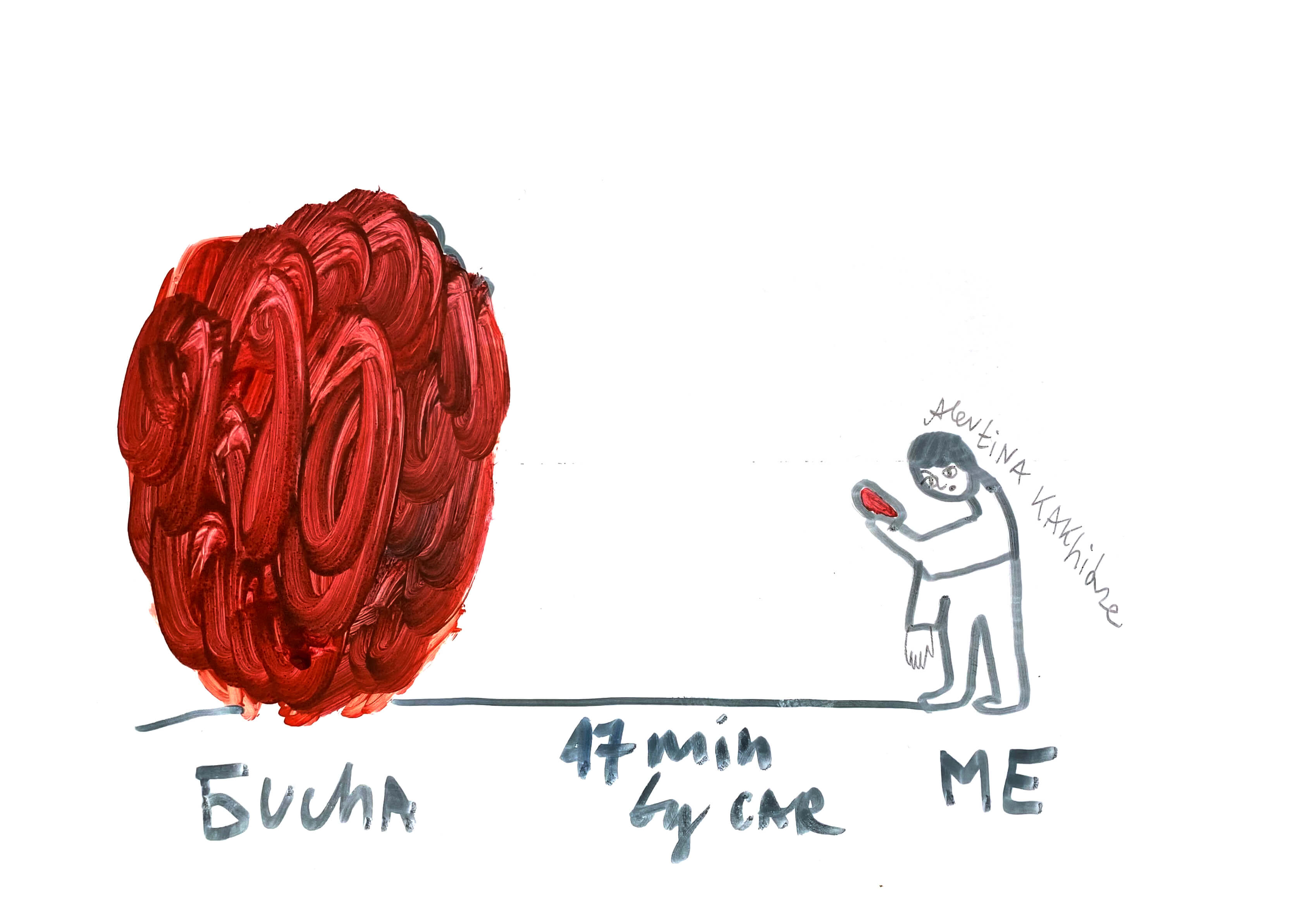

A Ukrainian feminist artist with Georgian roots and Jan van Eyck Academie alumnus, she co-founded a private residence for international artists in the town of Muzychi.

— The dynamics of coping with grief and reacting to war differ from person to person. When my mum died in 2019, I didn’t shed a tear. During the five years of her life under occupation, though, I cried a lot.

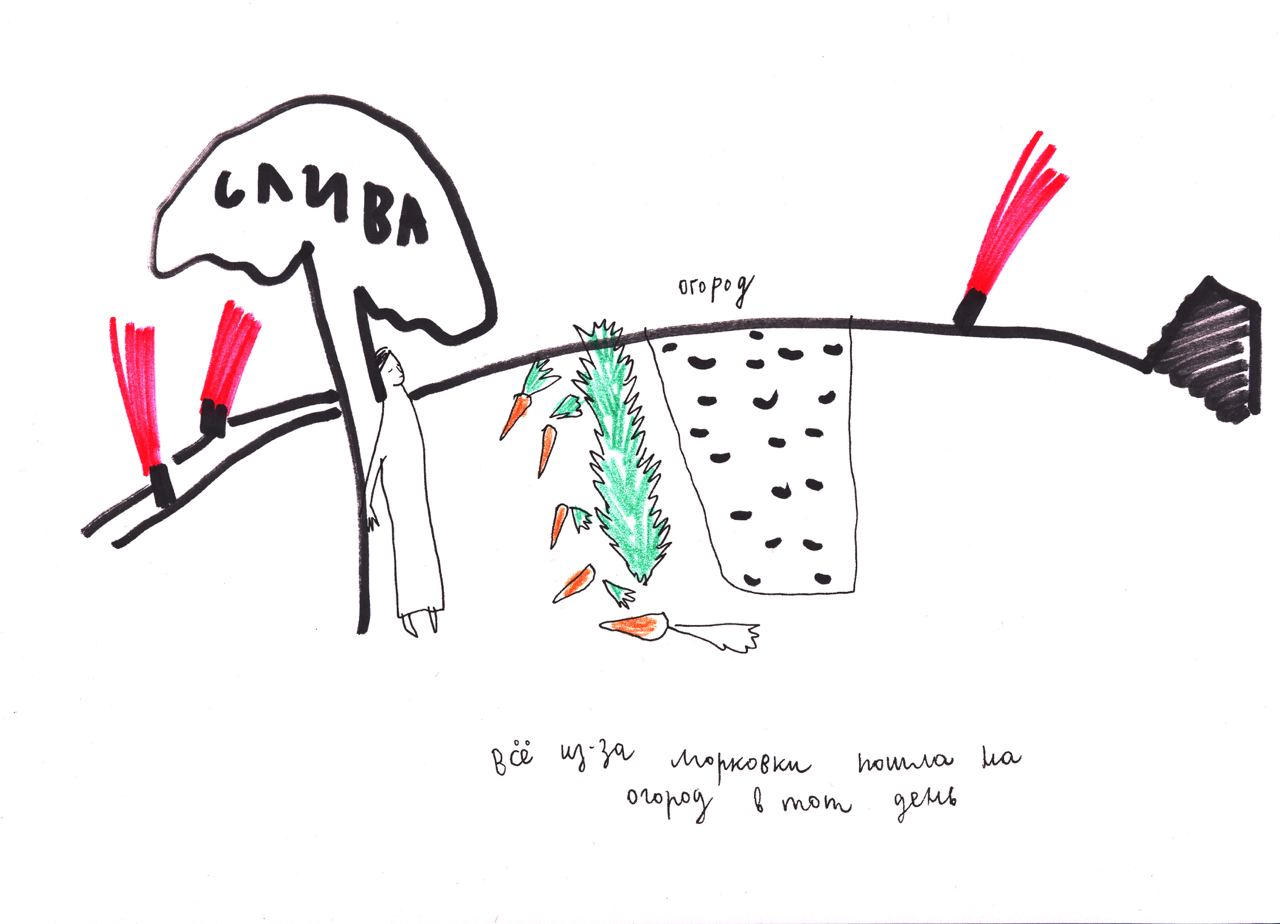

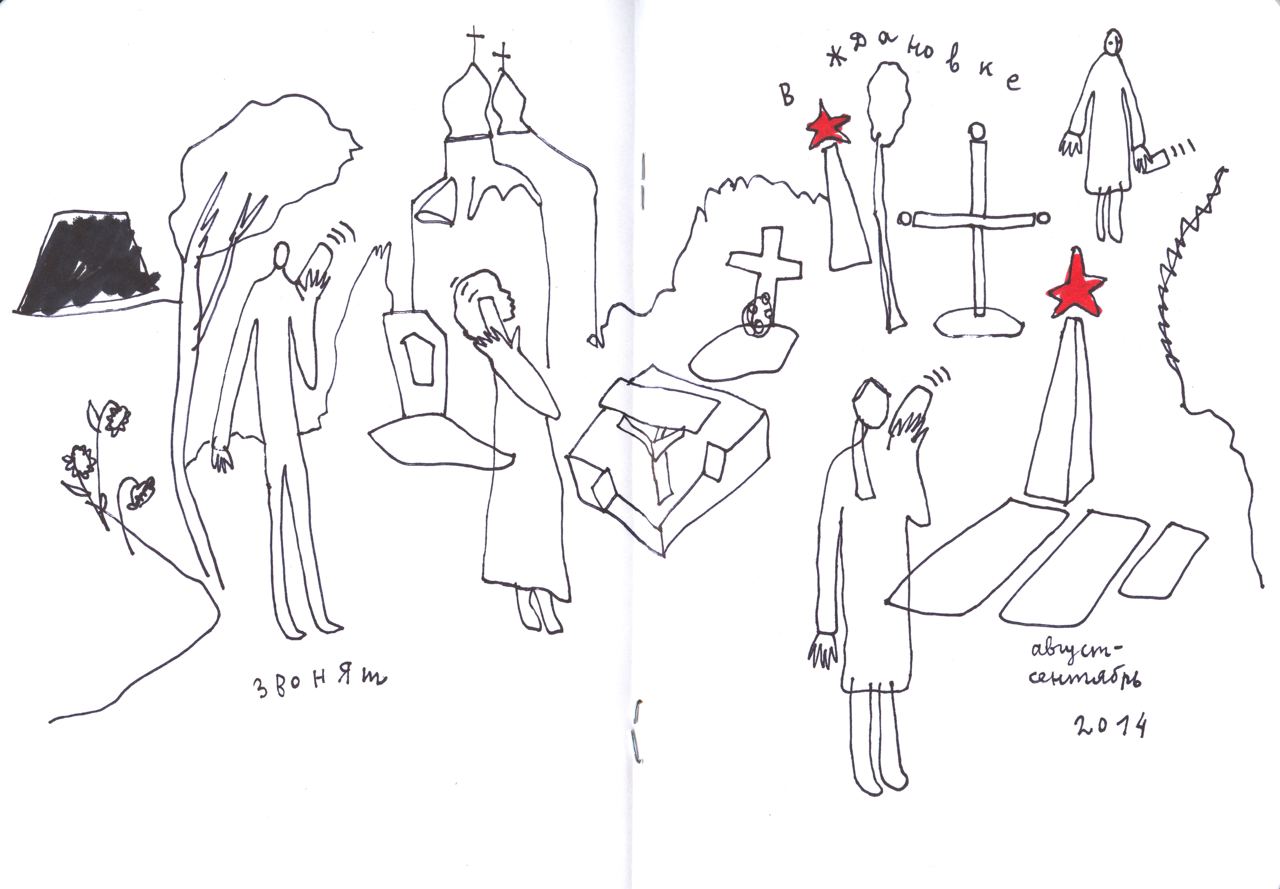

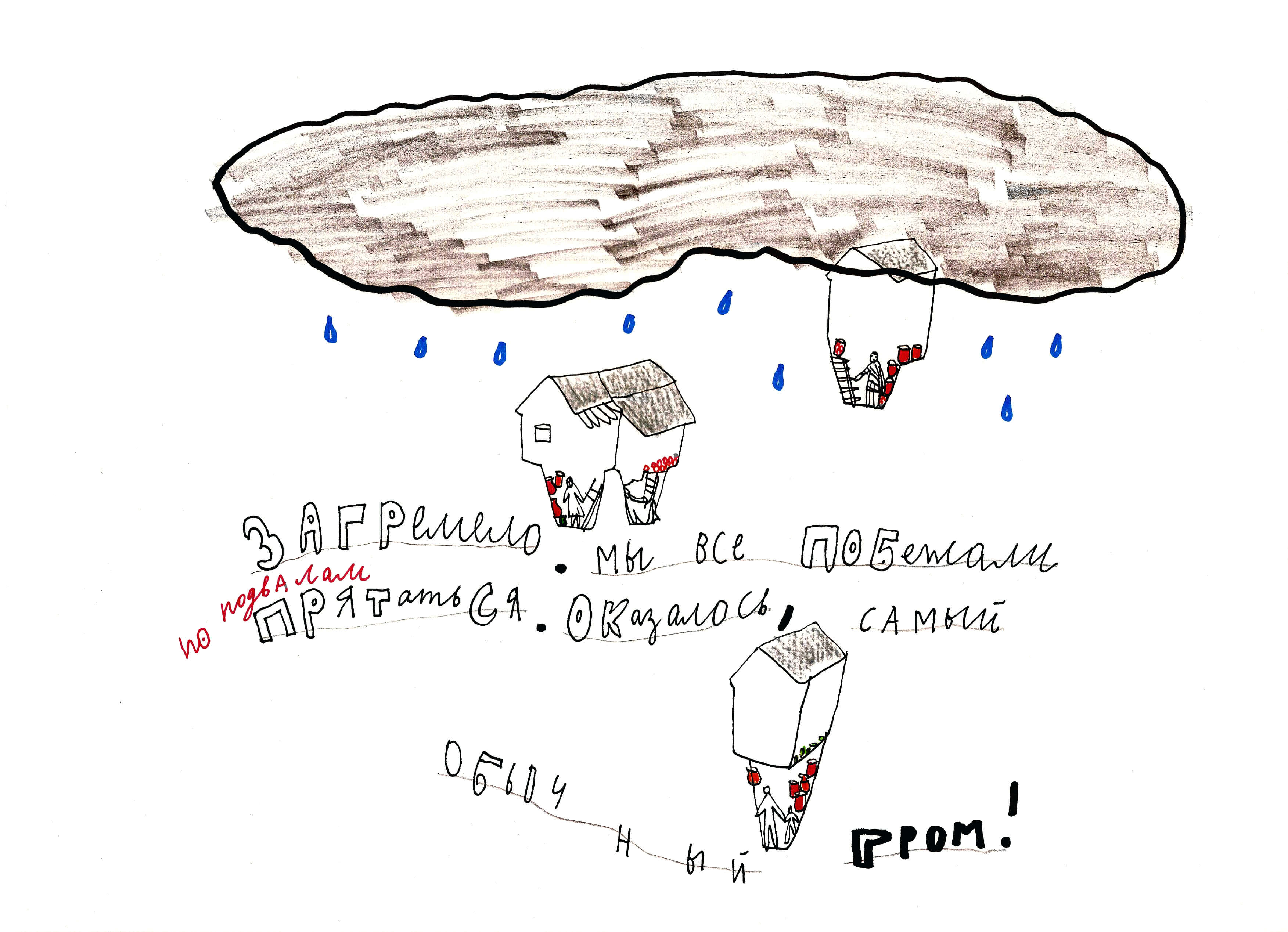

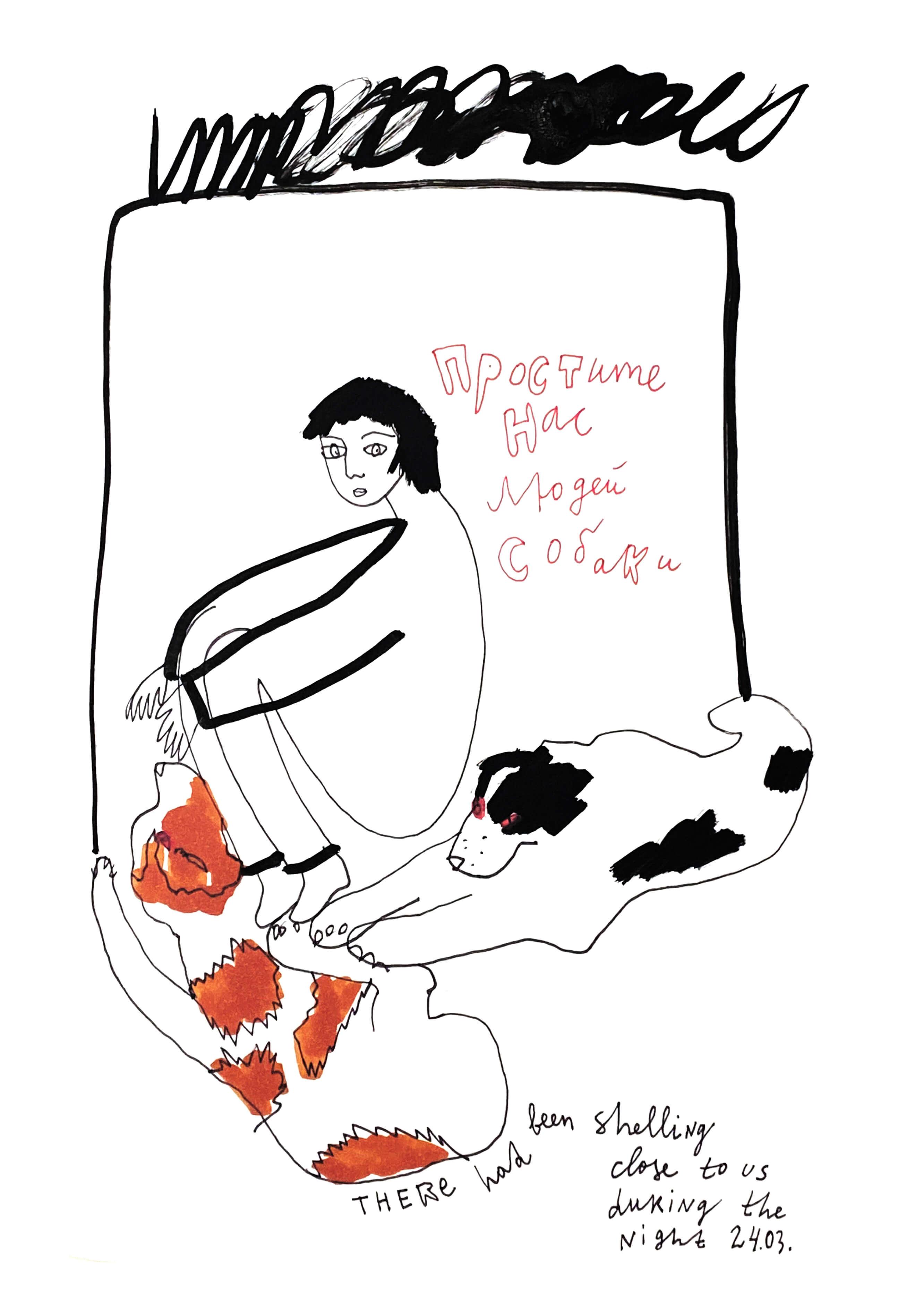

She used to teach at a kindergarten. One kid started calling her Klubnika (Russian for “strawberry” — Translator’s Note) Andriivna. I turned this nickname into a pseudonym to retell my mum’s stories about her life in the occupied Zhdanivka. In 2014, they resonated with only a few people. Nowadays, every Ukrainian understands and experiences everything she went through. For instance, I have a drawing about how the rumble started there, and everyone rushed to their basements. In the end, it was just thunder.

While my mother’s decision to stay in Zhdanivka felt questionable at the time. Now, many have realized what it’s like — not being willing or able to leave and lose your home no matter what. Klubnika Andriivna’s stories changed many people’s attitudes toward Donbas. Those who have never been there thanked me for bringing it to life in their imaginations with those stories.

Now, many have realized what it’s like — not wanting or being able to leave and lose your home no matter what.

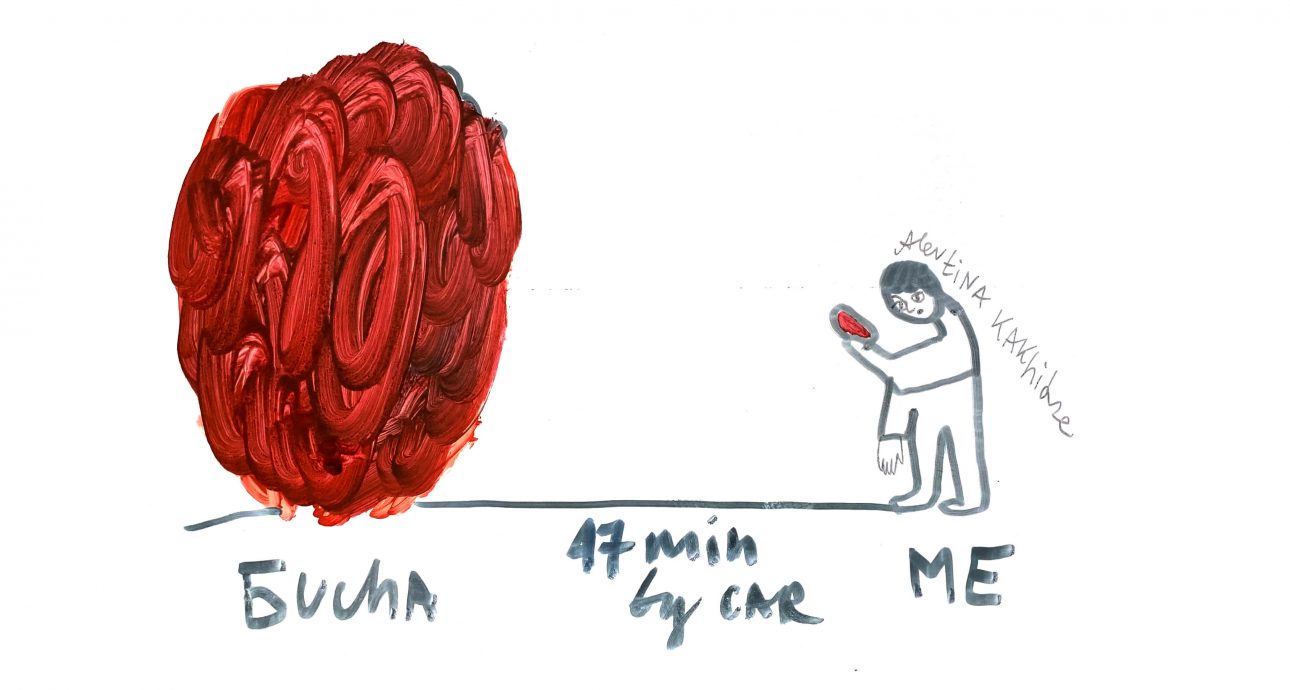

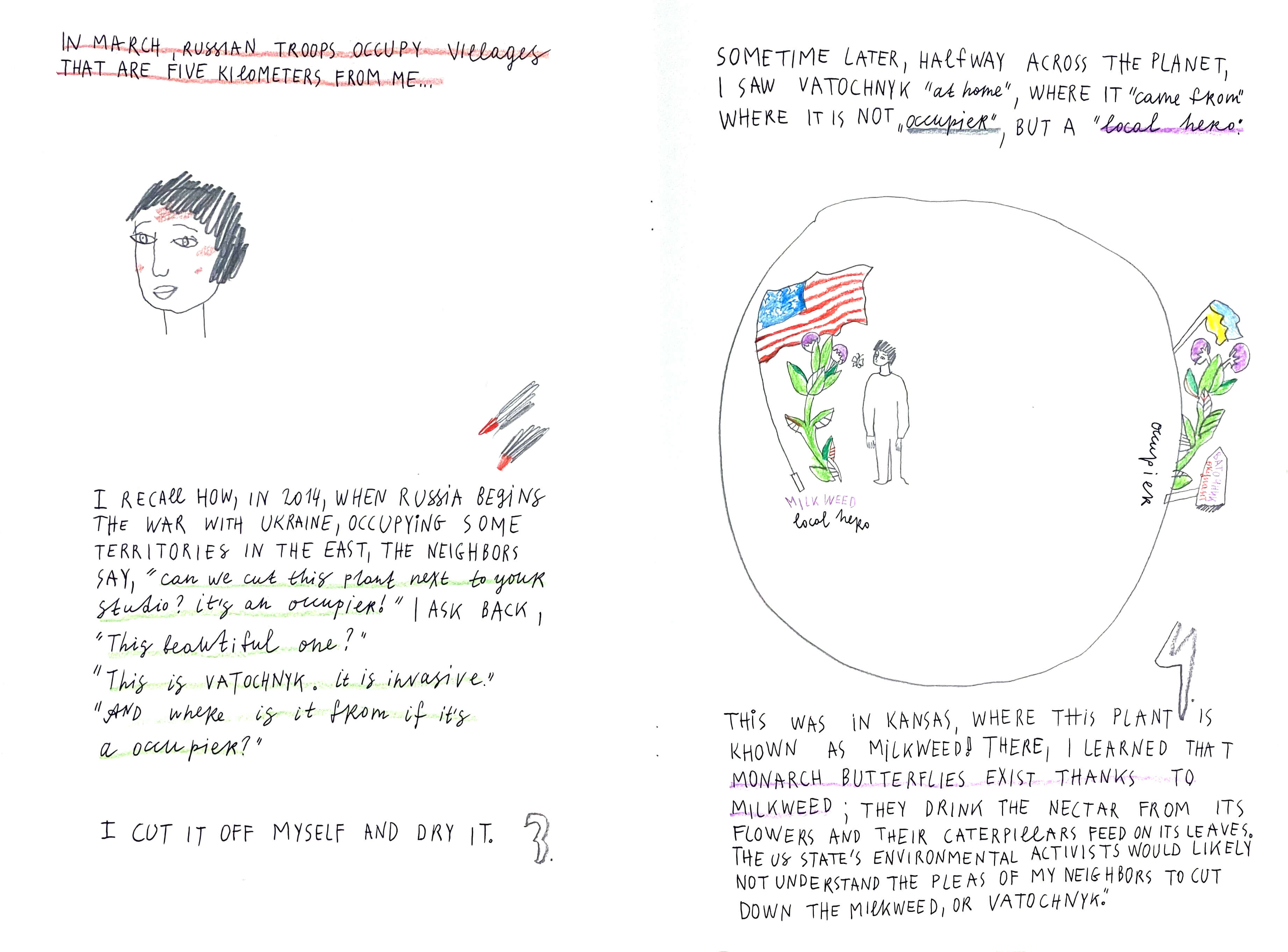

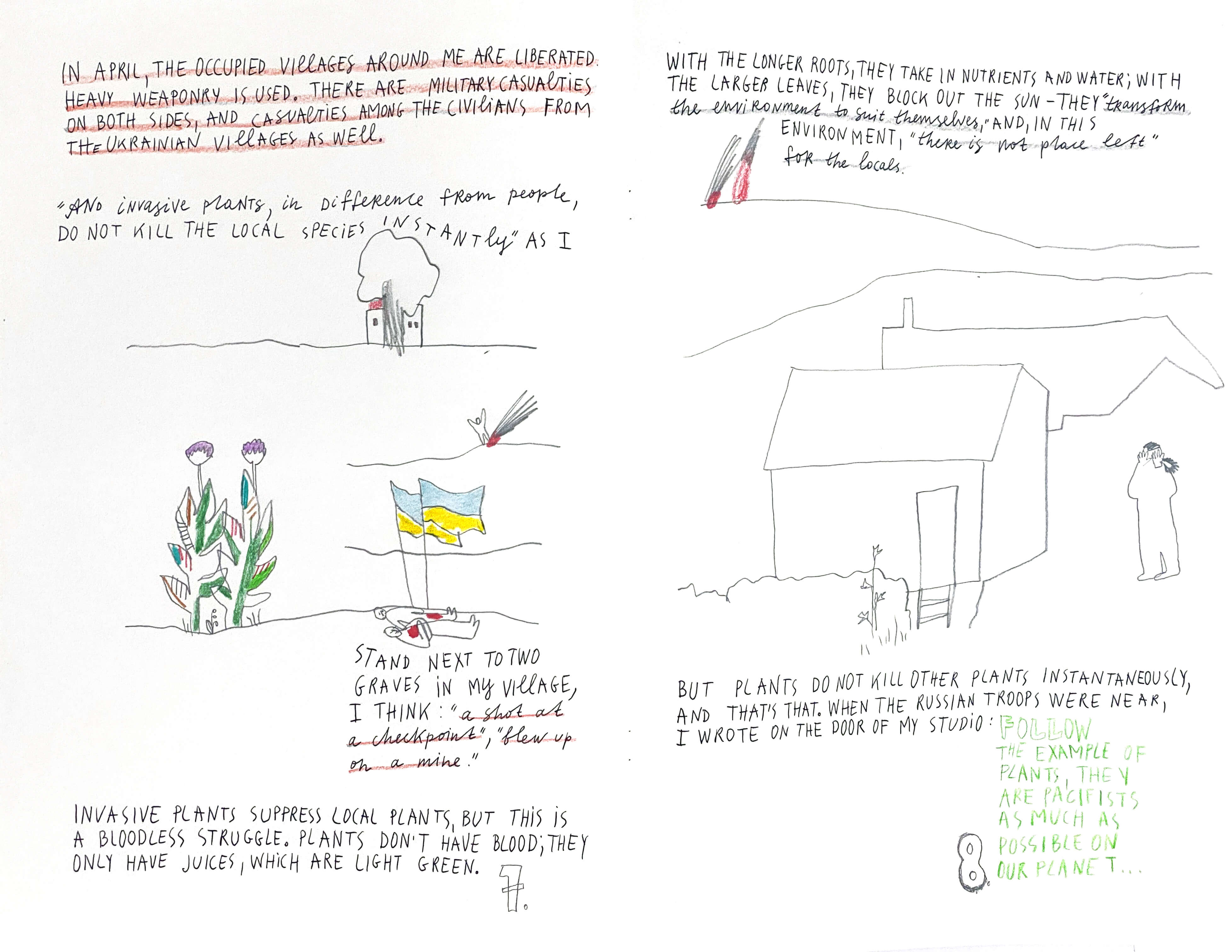

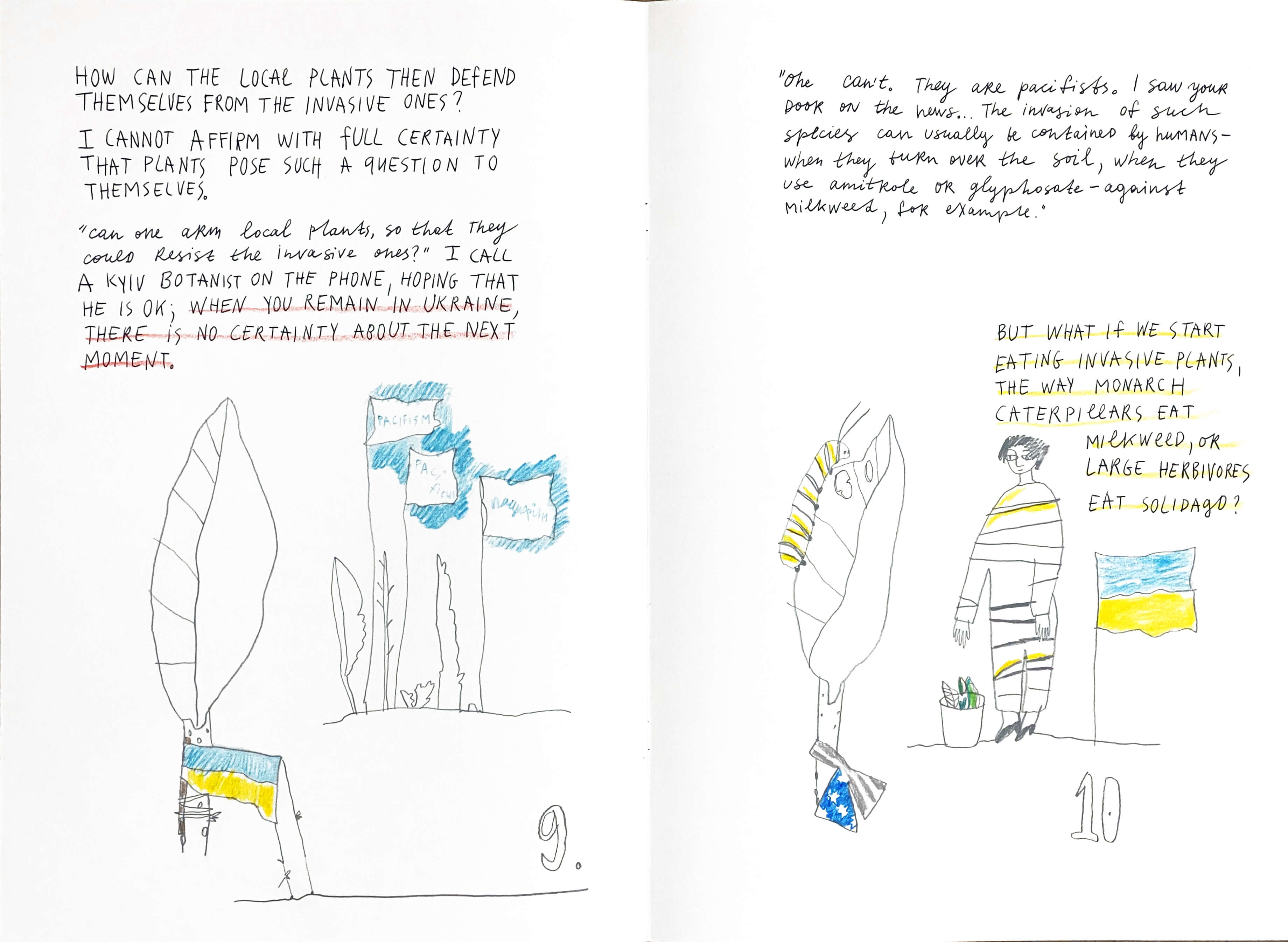

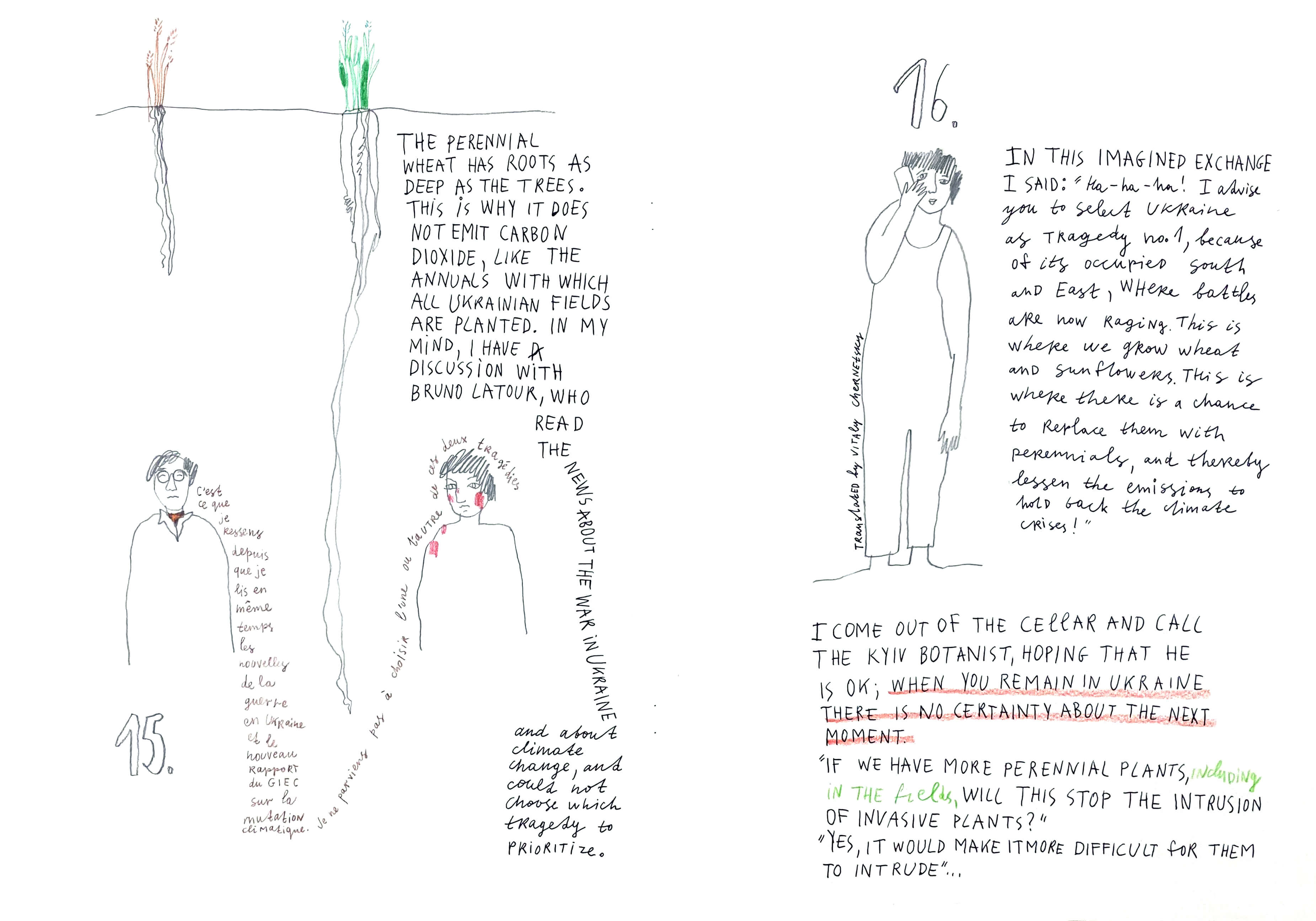

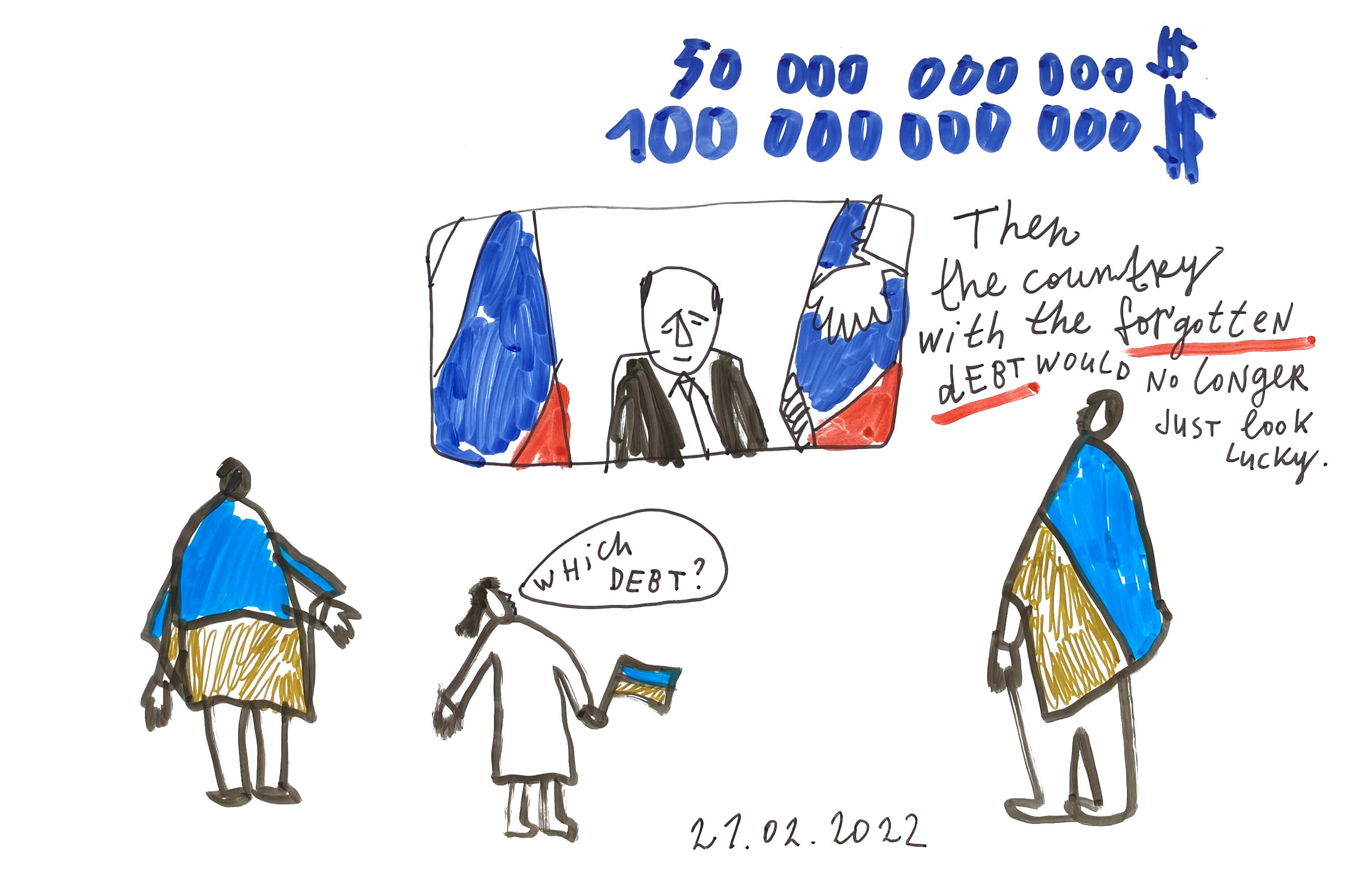

I’m in Kosovo now, at the Manifesta 14 biennial. Like all Ukrainians, I closely follow our infospace. At the biennial, I present my work about invasions that combines the Russian invasion and invasive plant species. My graphic novel is about a person suffering from the invasion — it’s my own story, and I also convey it through the struggle in the plant world.

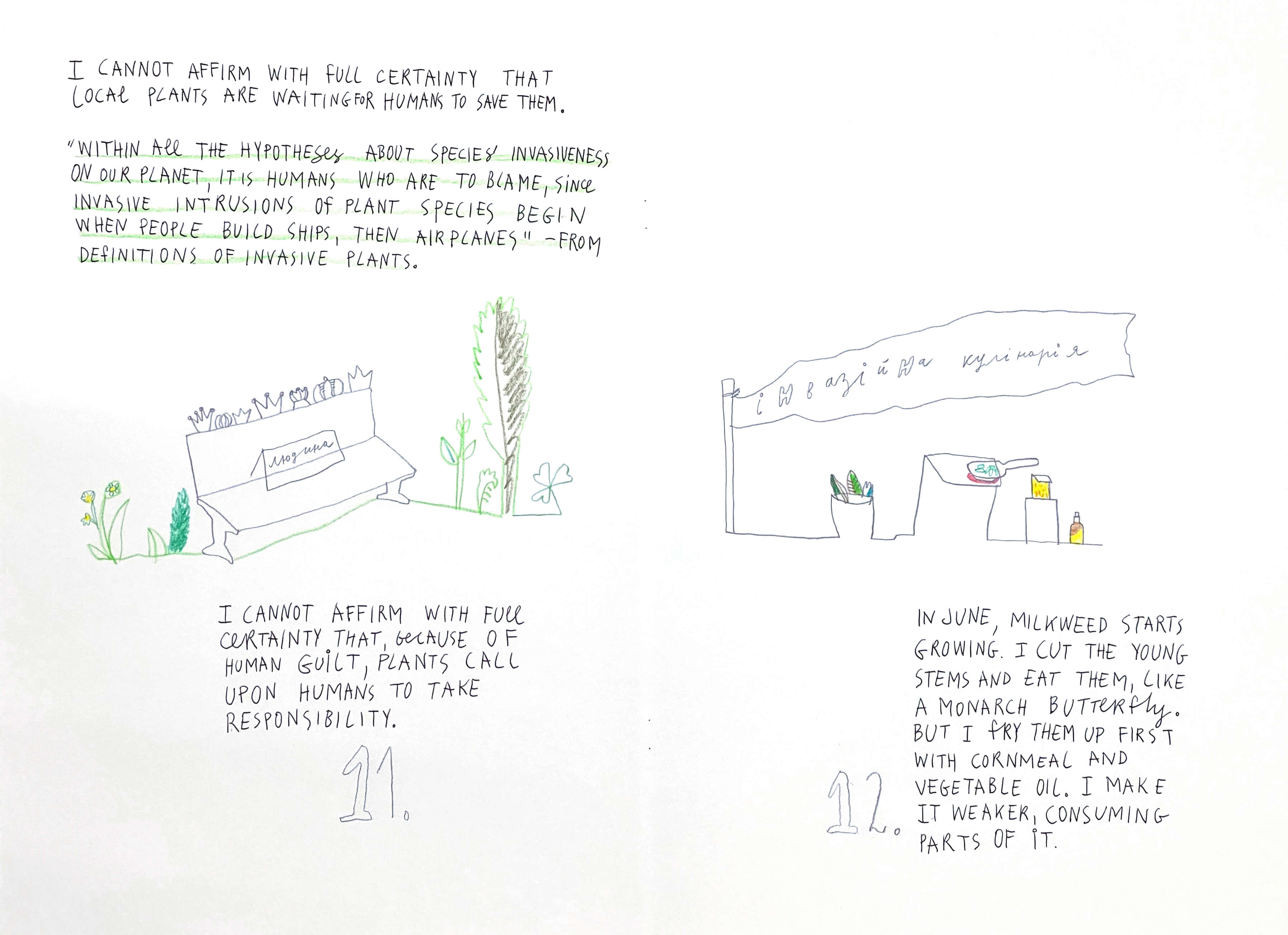

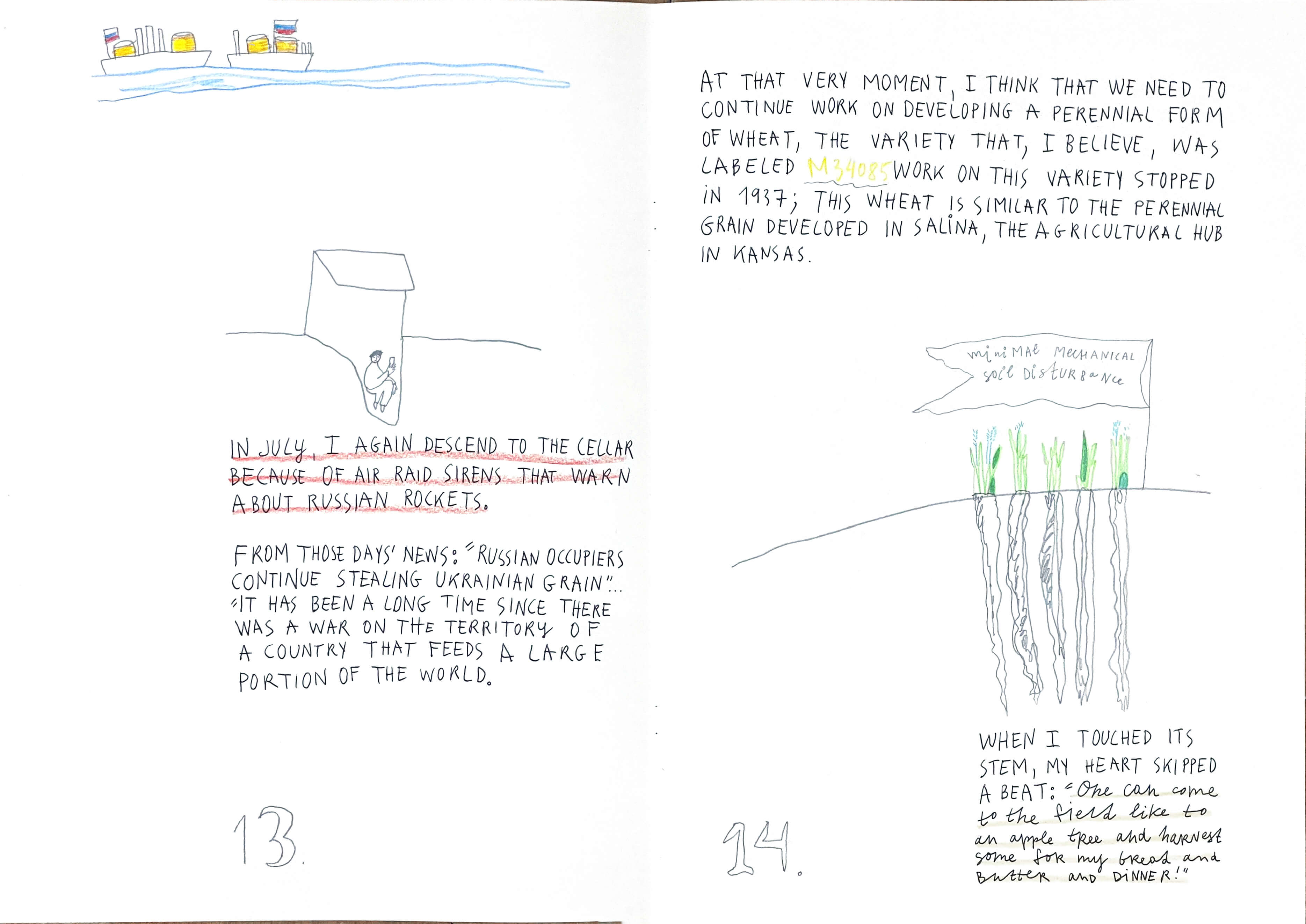

According to some hypotheses, it was humans who provoked invasions in the plant world by intruding into the world of flora and moving plants between continents. This is exactly the case of milkweed. Here, we don’t have its natural enemies — the Monarch butterflies, whose caterpillars eat this species’ leaves. As a result, milkweed encroaches on our indigenous plants. This disaster is deeply symbolic for our country.

In my work, I have found a way to achieve victory. As it turned out, the indigenous people of milkweed’s place of origin — South America — ate its young leaves. There is no doubt some symbolism in that — like devouring your enemy and taking its strength before it devours you.

In 2014, I participated in Manifesta 10 held in St. Petersburg, which was on the verge of cancellation because of boycotts due to the political situation in Ukraine. To this day, my friends keep reminding me it was a mistake on my part to participate in it, especially since the event had little to no effect on the Russians, as the current situation shows.

Attitude toward the Russian culture varies in Ukraine nowadays, including when it comes to cancelling it. As I see it, we need to take another look at the Russian culture and analyse it before we cancel it.

Take Ukrainian artist Kazimir Malevich, for instance. He was born in Kyiv, a part of the Russian Empire at the time and studied at Mykhailo Murashko Kyiv Drawing School. Later, he taught at the Kyiv Academy of Art and held solo exhibitions in Kyiv. Looking back at the sequence of events, you can see that it’s not appropriation on the part of Ukrainians (although such accusations are possible) but mere facts.

Do you know what Malevich thought of himself? In a letter to artist Lev Kramarenko, he wrote, “I don’t want to be a Ukrainian. What kind of despicable nation is it?” If you don’t want to be something, you identify yourself with it. His outrage was due to a fairly mundane situation. Malevich left some of his canvases in Kyiv, and they had to be sent to him to Moscow, but it took too long.

Do you know what Malevich thought of himself? He wrote in one of his letters: “I don’t want to be a Ukrainian. What kind of despicable nation is it?”

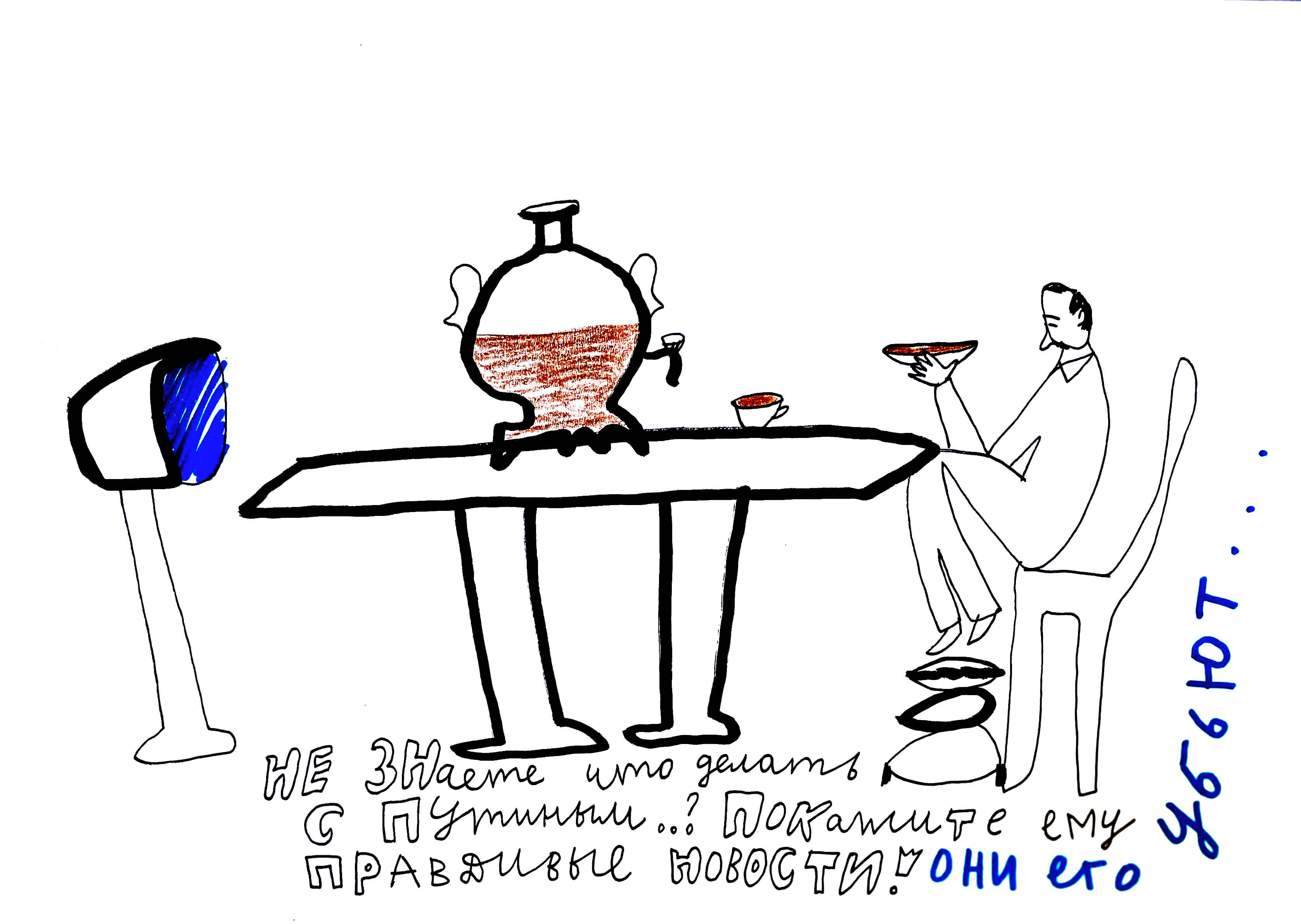

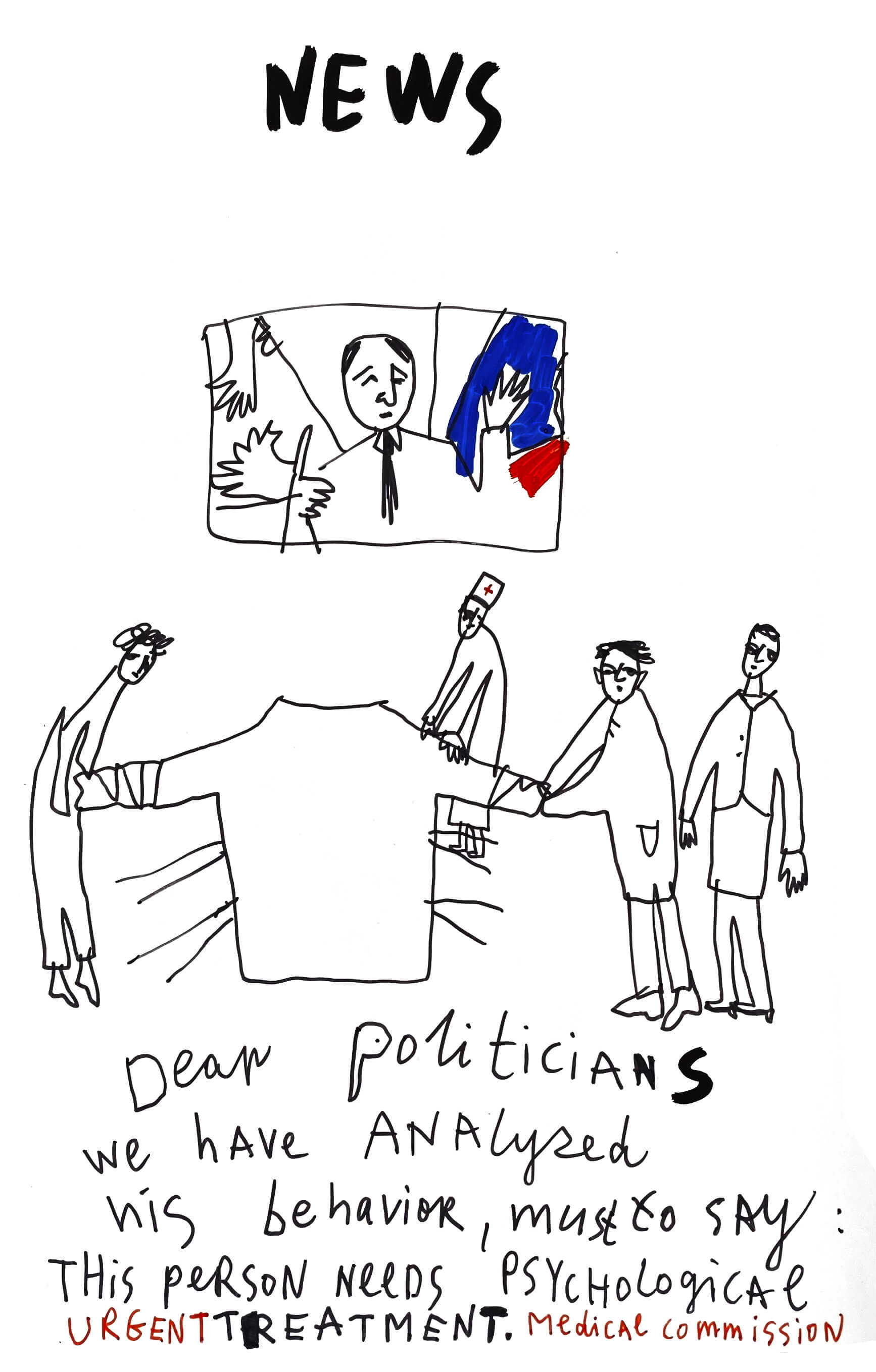

Speaking of the present-day Russian culture, I allude primarily to the Russian intellectuals. Those are usually people of influence. However, they take no action against the Russo-Ukrainian war and don’t even try to influence their audience, so one might as well question the existence of any intellectuals in Russia right now.

Many of my Russian colleagues from among artists can’t display their pieces in today’s Russia. They have been unable to openly discuss the war in Ukraine with their compatriots since as early as 2014. Therefore, they exhibited their work in the West and lost connection to their audience at home. When the full-on invasion began, they had neither a platform nor skill to talk to their fellow countrymen about it. So, what did they do? They fled Russia or kept silent like before.

In March of 2022, the so-called Law on Discrediting the Russian Armed Forces came into force. However, the first real sentence under it didn’t follow until July, when Russian municipal deputy Aleksey Gorinov was convicted for calling the war the war during a deputy council. I remember how Berlin-based curators talked about the dangers of this law for my Russian artist colleagues and worried the latter were being “put in prison there”.

I consider my Russian colleagues labour migrants, even though they beg to differ, calling themselves refugees. Other Russian artists claim to be dissidents. As I see it, however, dissent is a form of protesting the official regime that is as open as possible as opposed to just sitting in one’s kitchen and “quietly resisting”. For one, I have no doubts about Maria Alyokhina being a dissident, as she spent two years in prison for the Mother of God, Chase Putin Away punk prayer in a Moscow cathedral.

As I see it, dissent is a form of protesting the official regime that is as open as possible as opposed to just sitting in one’s kitchen and “quietly resisting”.

I stay in touch with some of my Russian colleagues, but those are not exactly public people. One of them is a St. Petersburg-based artist who has been detained and put into the investigation ward twice since February for protesting.

Speaking about the Russians’ inaction for fear of going to prison reminds me of Maidan, by the way. When they bundled us away, we were afraid, too. We, too, had children, parents, and close ones, and we didn’t know what was next for us. We couldn’t know that amnesty would follow after the 20th of February, and the prosecution of Maidan participants will cease. Similarly, Russians don’t know for sure if they will spend all of those 15 years in prison if they get such a sentence. Breaking the silence and taking action is thus a matter of choice.

But we can’t and shouldn’t look back on the Russians. It’s against their countrymen that the arms supplied by our allies are used, and it’s their people who come back home with their limbs missing or even in zinc coffins. Everyone now has a chance to do what they believe necessary. What we need is to grow up because finding solutions and making decisions is what adults do, while all children do is complain.

The Europeans don’t understand us either. They can’t feel the disgust of a person hearing the Russian speech in their city or town under occupation, reading a Russian book, or listening to Russian music under the current conditions. We have found ourselves in a situation where we turned out not exactly the same as in our peaceful life. It happens on a primal level of some kind, where there is no place for emotional intellect.

These are the times of identity crises. For instance, the issue of women picking up arms and going to the frontline has gained utmost prominence now. Two of my female friends — a journalist and Maidan case activist — have joined the Ukrainian army. My thoughts are with them every day.

For instance, the issue of women picking up arms and going to the frontline has gained utmost prominence now.

Over the 20 years of my artistic career, I have covered all the feminism-related issues I could: appearance, responsibilities, reproductive violence, and the right to choose. My path to making adult decisions was difficult, and I see feminism as a reflection of high level and maturity.

I believe the importance of the feminist perspective in the Russo-Ukrainian war is hard to underestimate. It’s essential for a woman to be able to defend her space and achieve full independence and separation in situations where a man is undoubtedly stronger.

There is an opinion in some feminist circles that wars are nothing more than men’s play, and their cause is toxic masculinity. As I see it, they somehow confuse war as masculine play and liberation war, during which men and women alike suffer under occupation. Still, Russian aggression is indeed partly due to toxic masculinity. Otherwise, why would their Security Council include mostly men? Also, it’s funny how Putin compares himself to Peter I. As writer Andrii Bondar noted, Putin is more akin to Catherine ІІ in his attempts to “gather the Russian lands” if we look at history without gender preconceptions.

New and best