Bloody Trace in Alyona Tokovenko’s Works

A Ukrainian artist. Finished Grekov’s Odesa Art College. Currently works at an artists’ residency, Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris.

— I talked to my grandfather about World War II a lot. And now I am the one who lives through historical events. When the full-scale invasion started, I wasn’t afraid or panicking. I just knew that an epic thing was going on. I wanted to commit to memory the images of war, but we were not allowed to take pictures of the military objects. Once, after a missile attack at Dorohozhychy, I gave it a try. I was curious about what our bomb shelter looked like and I tried to take some photos. Afterward, I had to explain to the military that I was not a part of a subversive group.

We went back home from the bomb shelter and dove headfirst into watching the news. Back in the day, it was impossible to work with large canvases. I started to make graphic sketches while watching the news online. For me, graphics have always been a way to think, rather than a proper art form. I would catch a phrase from an interview and subconsciously depict it on a piece of paper. I was creating my “travel notes”.

For me, graphics have always been a way to think, rather than a proper art form.

Oksana Andreeva, an artist known as AntiGonna and a friend of mine, kept urging me to join her at an artists’ residency Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. She insisted that I should flee Ukraine. She couldn’t understand why I was sitting so calmly in Kyiv and told me that there was no worse thing at war than calmness. But I was paralyzed and found no sense in anything. Finally, I pulled myself together, packed my things, and left. I started painting only when I crossed the border.

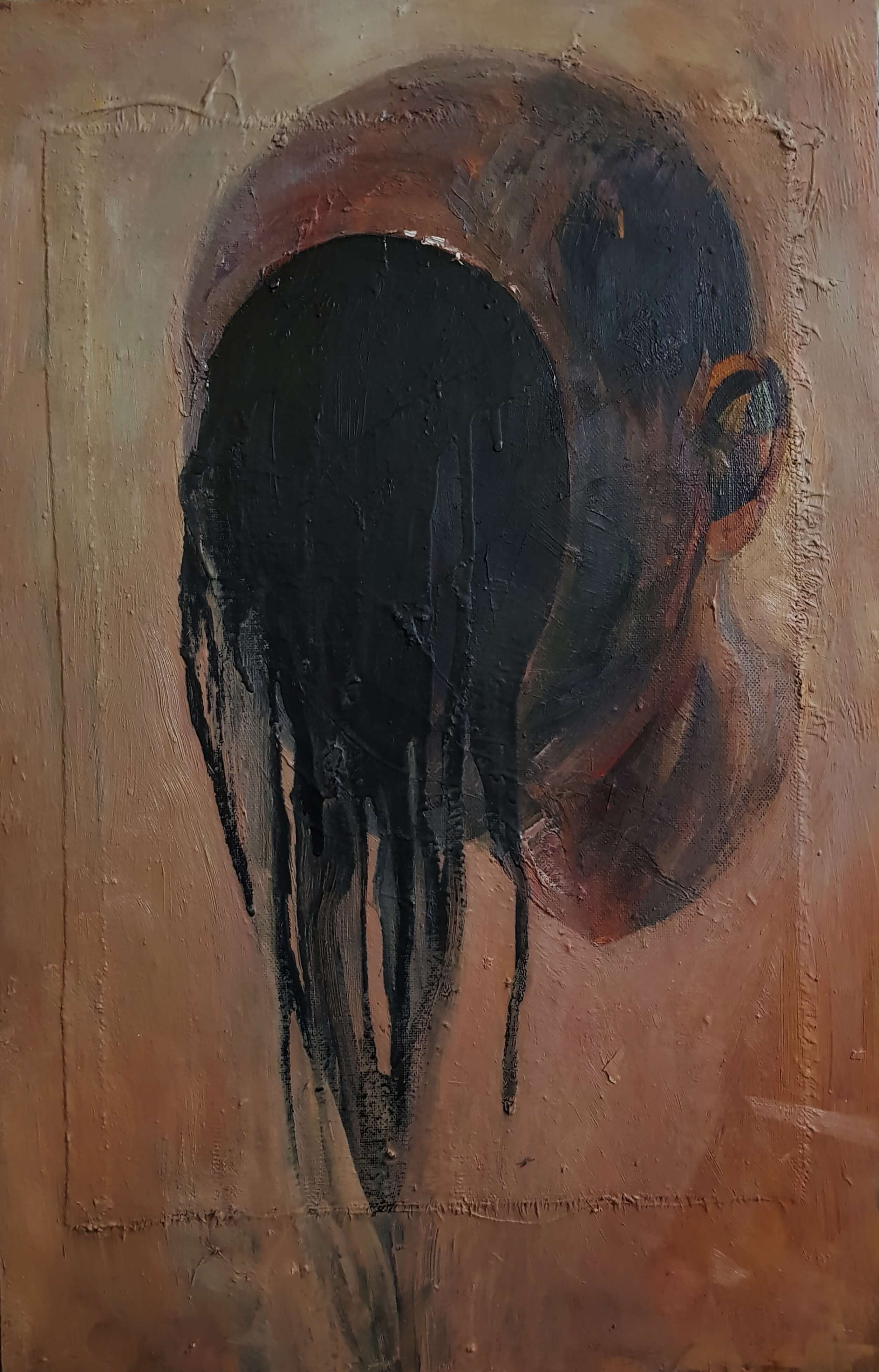

I have always worked with rather bloody narratives. I explore reality through pain and violence — turning points of our lives. Before the full-scale war, I was obsessed with two projects, and their meaning changed a lot since February 24.

The first project was about the violence we see in forensics photos. For instance, a crime was committed and documented. But we can never know what has actually happened by simply looking at the photo. A big chunk of time is missing. I wanted to bring it back. I made a homunculus that represented a wrecked human body. We placed it on a mattress and took pictures of it in a way forensics do. Then we moved it to a gallery and placed cameras and screens in the other room so that people could watch the scene live.

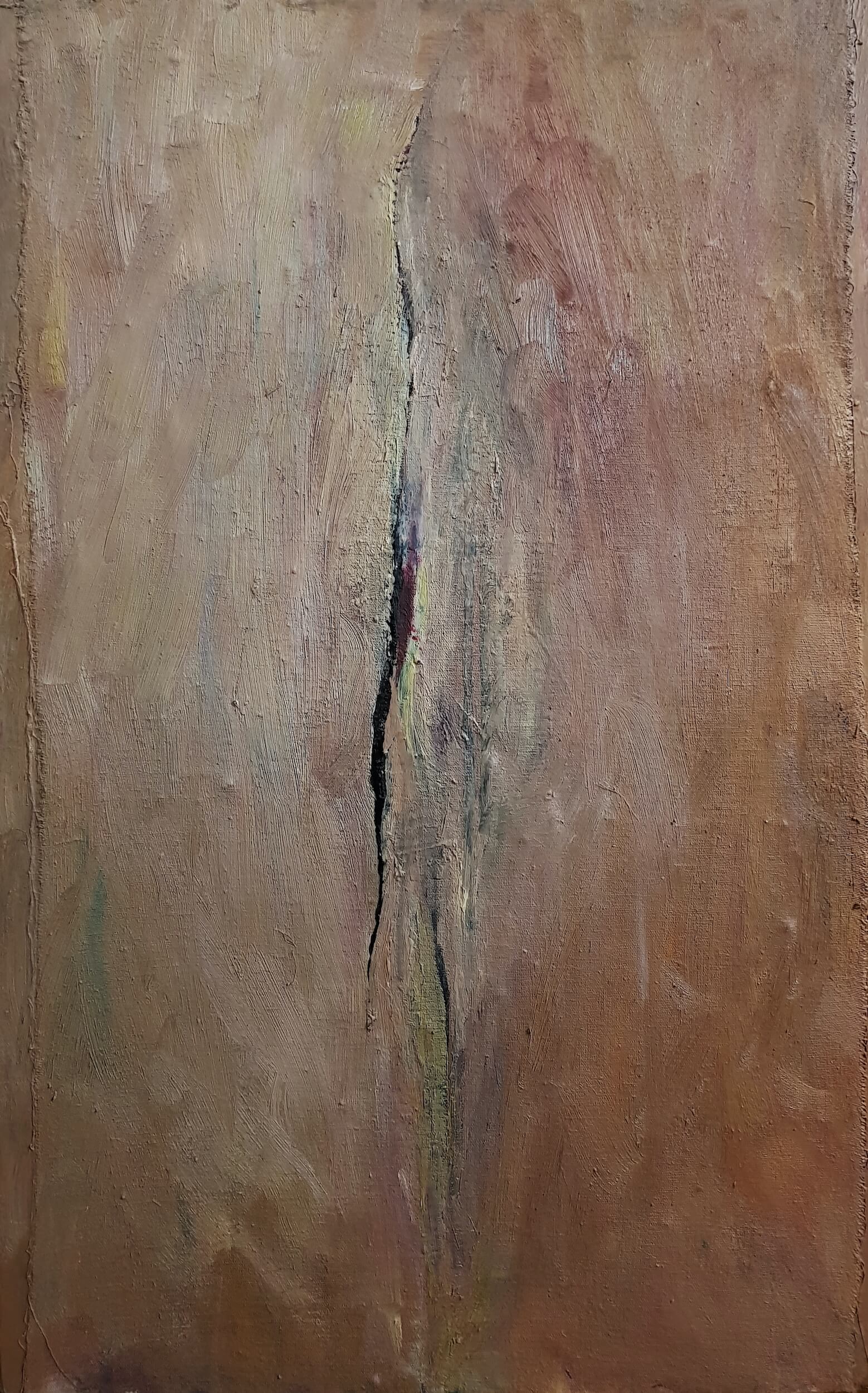

The second project was about mattresses. I’m deeply interested in this household item. On one hand, everyone has a mattress, it’s an intimate, close-to-the-body object. On the other hand, mattresses can be very public, lying around on the streets. Besides, terrifying things like death and violence happen on mattresses oftentimes. I wanted to create an installation where mattresses would become canvases.

And then the war started. I went down to the metro station and saw everything that my imagination pictured: mattresses lying on the floor, private and public lives intertwined. Once I was walking down the street and saw a corpse covered with a plastic bag. A piece of paper pronouncing the death lay nearby, pinned down with a rock. This body didn’t look like my homunculus. It didn’t look like the corpses that I saw in the city morgue. It was all different.

Once I was walking down the street and saw a corpse covered with a plastic bag.

At that moment, I thought anxiously that I should stop inventing installations that come to life before my eyes. I was sure I wouldn’t be able to create any more bloody paintings. But eventually, I understood that it was the only thing I could think about. Now I work on a project that is called “A victim’s costume”. It’s an exaggerated cross, on which visitors would be able to lie down. I’m reflecting on how people force the image of a victim onto Ukraine and how they start pitying me as soon as I tell them that I’m a Ukrainian. This is a wrong and dangerous tendency. I would want people to see us as a strong nation, a strong country.

Another idea that turned into a series of works is related to insects. In these paintings, I reflect on people’s lost ability to tell living creatures from dead ones. I remember seeing an insect in my apartment. I couldn’t kill it. I think, the full-scale war deprived me of the ability to squash a living creature. I realized that I feel like an insect myself—someone can crush me down at any moment.

I think that now is not a good time to dwell on my own trauma. I can paint it, but I can’t cry over it. If we want to save ourselves and others, we have to work now: to make statements, speak out, raise funds, or paint.

Now is not a good time to dwell on my own trauma.

I used to think of my work as a kind of therapy. Now it becomes a way of communication. A lot of people in Europe know nothing about Ukraine and the Ukrainian people, they get distracted by their own problems and forget about the war. That’s why art should keep their attention focused. Art should explain what’s going on and wake people from their apathy. But artists should dig deeper and grasp difficult narratives. Drawing Putin’s suicide and a blue-and-yellow flag is not a thorough discussion of Ukraine. It achieves nothing but lulls people into slumber. We have to talk about painful topics and ask complicated questions. My whole life I’ve been told that my works are overcomplicated and untimely. But I keep working.

New and best