Mark Neville: Civilian Life Seems Utterly Meaningless When You Return From War

British photographer. Started his career as a sculptor and an artist. Has degrees in Fine Arts from Reading University and Goldsmiths’ College in London. His works lie between art and documentary. In 2011, he spent three months in Helmand province in Afghanistan together with the 16th Air Assault Brigade. The exhibition of his photographs and videos took place in The Imperial War Museum London in summer 2014. He recently published a book together with professor Jamie Hacker Hughes, one of the UK’s leading experts in the field of veteran mental health, called The Battle Against Stigma, about the psychological rehabilitation of service personnel.

I'm an extremely driven, hard-working, passionate person. And kind, I hope.

I have no family or kids, as yet, and I still focus a great deal of my life on my work. I live alone in London, in a work/live space which I love, a converted chocolate factory, but I do travel a lot for work and live in different countries for long periods in order to achieve my projects.

On His First Project

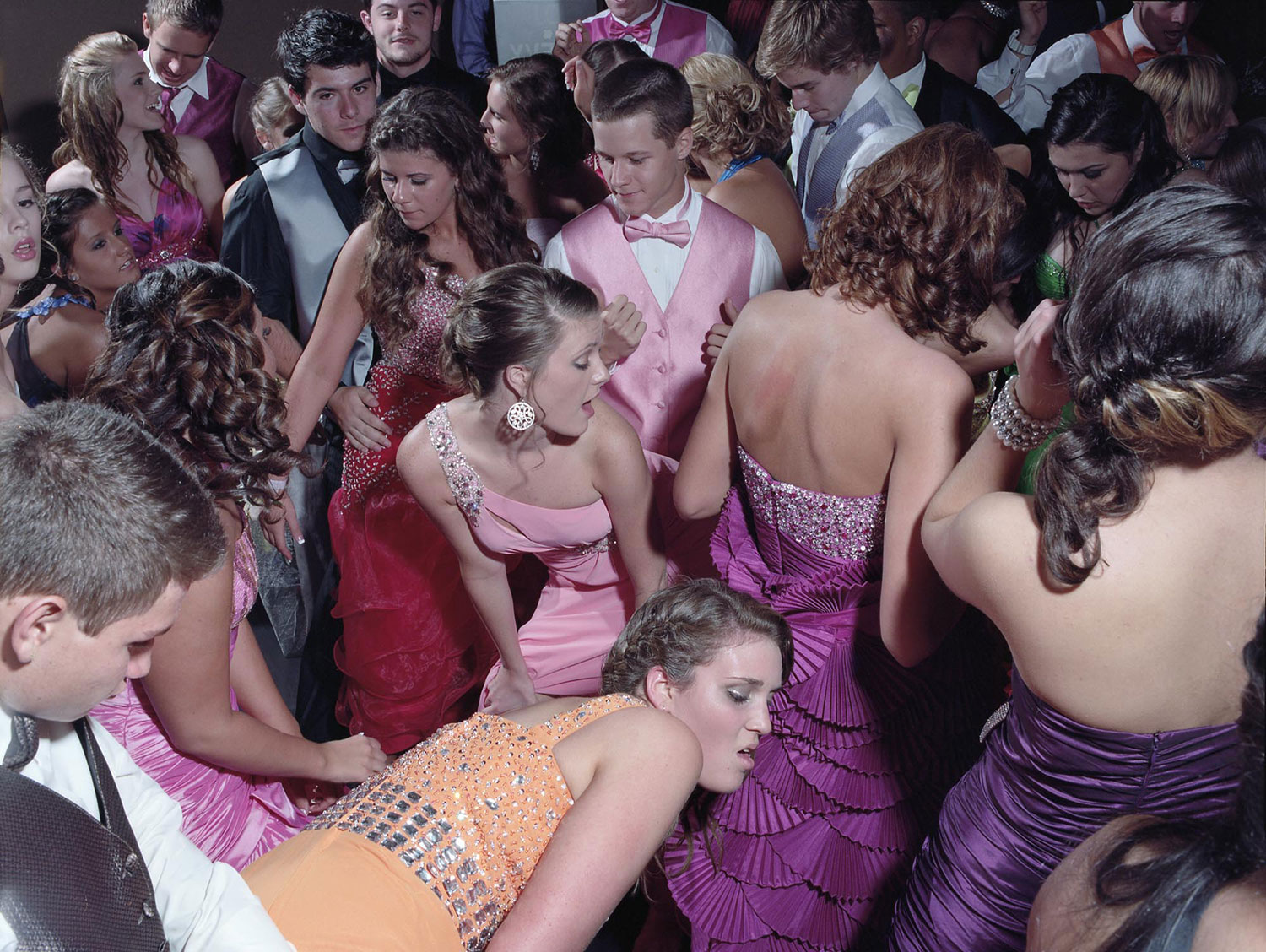

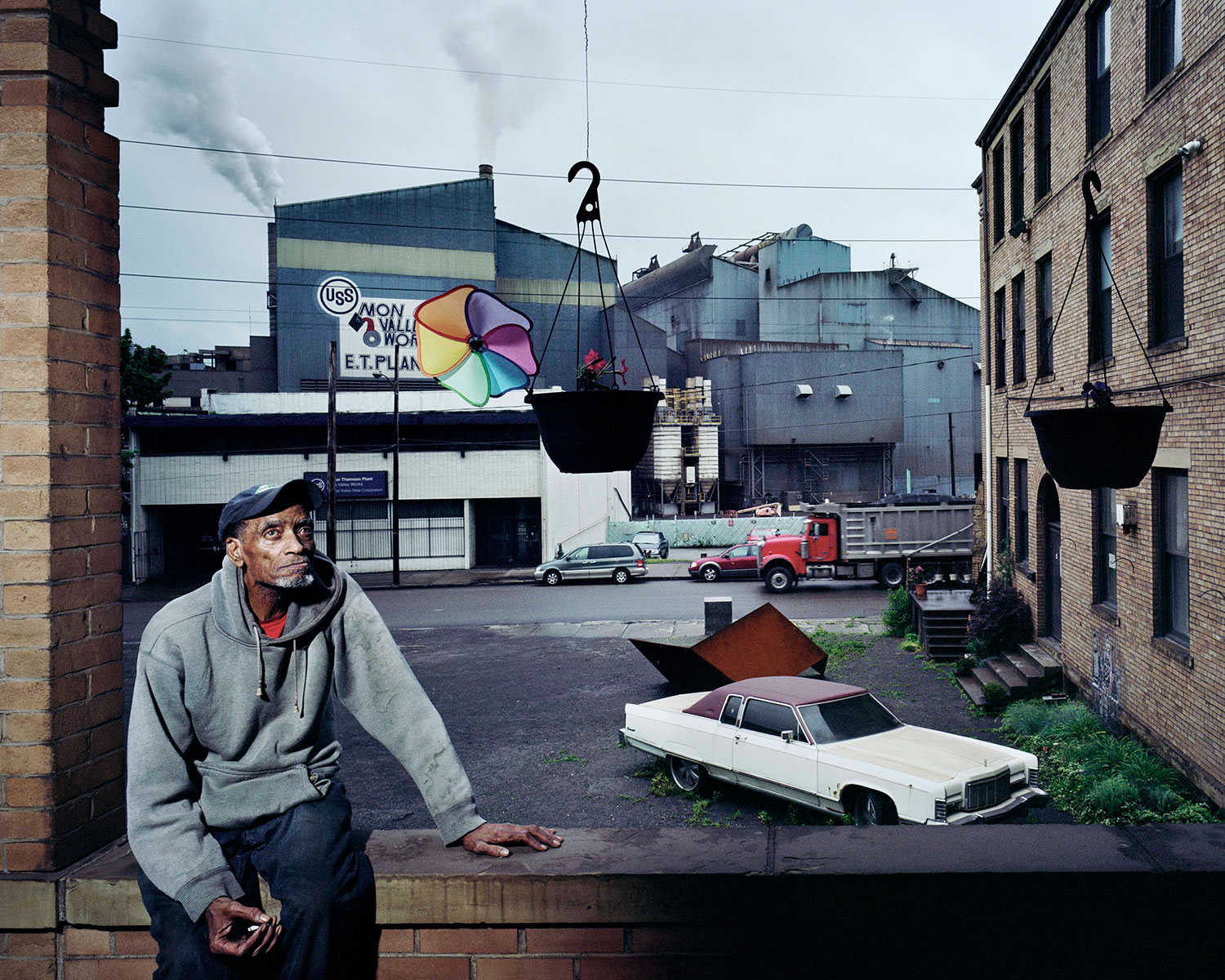

I used to be an artist and just made photos of my sculptures and installations. And, in 2004, I made my first documentary photo project. It is called The Port Glasgow Book Project (Mark Neville spent a year in the port of Glasgow, and photographed the city in its post-industrial decline. This photo project later turned into a book, which the boys from the local football team delivered to eight thousand houses. The book is not available anywhere else, commercially, by mail order, or otherwise. Neville’s concept was to literally bring the book to its characters — people who would never buy it in the store. — Ed.). After 11 years, I still love this project. It is the genesis of all my work as a mature, honest and thinking artist.

On His Own War Experience

In 2011, I spent three months with the British army in Helmand in Afghanistan. I remember it all like it happened ten minutes ago. It was the most intense experience of my life without a doubt. It was the most horror, the most stress, the most problematic, and I still cannot process everything about it.

He just used to shout at everyone in the family, and take photos of them with a box camera. Much later, my father committed suicide. It was a challenging childhood.

I think my grandfather used his camera as a way to try to mediate a relationship with the world, and I try to do the same now, I think. When I got offered this commission to be a war artist in Helmand, by the Imperial War Museum in London, I thought that it was an opportunity to uncover my own family's troubled history in a way, and find out why my grandfather was such a difficult person.

I understand war reporters who say real life is at war, and civilian life is boring. This is a perfectly normal reaction, and I felt exactly the same way. Civilian life seems utterly meaningless when you return. Like a myth, a bubble, a meaningless artifice. And the war zone still feels like reality, like real existence. However, I think this is unhealthy thinking, and I have worked hard to try to adapt again to civilian life in a constructive way.

When I first returned from Helmand I thought I was invincible, which no one is of course. I was overly confident about everything, to an extreme, and had no regard at all for social conventions. I started to get into fights and arguments, I began losing friends, and my relationship of ten years ended abruptly. So, after six months I realised something was seriously wrong, and I got treated for adjustment disorder, or 'PTSD'.

About His Work in Ukraine

The problem is that what we are told by the media, in every country, is so very different from the reality. If this huge gap between what we are told, and the truth, were even a little bit closer, then I think the world would become safer.

My upcoming project means that I will return to work in a war zone again. I cannot go into great detail at the moment for a few reasons, but this week I am taking photos of wounded soldiers at the Kiev Military Hospital. These images may be used by Ukraine Aid UK, a charity based in Britain which tries to support the victims of war. I am also setting up a much bigger project involving the establishment of a printing press. This is also based in Kiev, and will tell the stories of displaced people. I will be working in Ukraine and Russia for about two or three years.

On Censorship

My current book project, which will be translated into Russian and Ukrainian,' Battle Against Stigma', has faced huge censorship issues in Britain. It deals with PTSD among troops returning from war zones, and encourages them to come forward and seek professional help.

The book was printed in Spain, and shipped over in two consignments. The first consignment of 500 copies was seized by the UK Border Force at customs, a branch of the Home Office and the Ministry of Defence. It still has not been released. However, the second consignment of 1000 copies came to London via a different route, arriving safely at my studio. I then spent all summer furiously trying to get my book sent out, free, to prisons, homeless centres, and mental health charities. Basically to try to reach veterans who may have PTSD, but never had it treated, and thus encourage them to come forward and get help.

No matter what, I believe utterly in the value of what I am doing, and this belief gives me the strength to persist, and to take photographs of things that maybe others would not be brave enough, or stupid enough, or patient enough, to do.

I'm British, but nobody is perfect.

New and best