Author of Chernihiv’s Reconstruction Concept on the Project’s Destiny: “Nowadays, Developers Think about the Present, not the Future”

Victoria Yakusha has built what might be called an exemplary career. An architect by trade, she founded Yakusha Design (an award-winning architecture and design studio), won design awards, and established a successful furniture and decor brand—FAINA—imbuing it with her own flavour of minimalism.

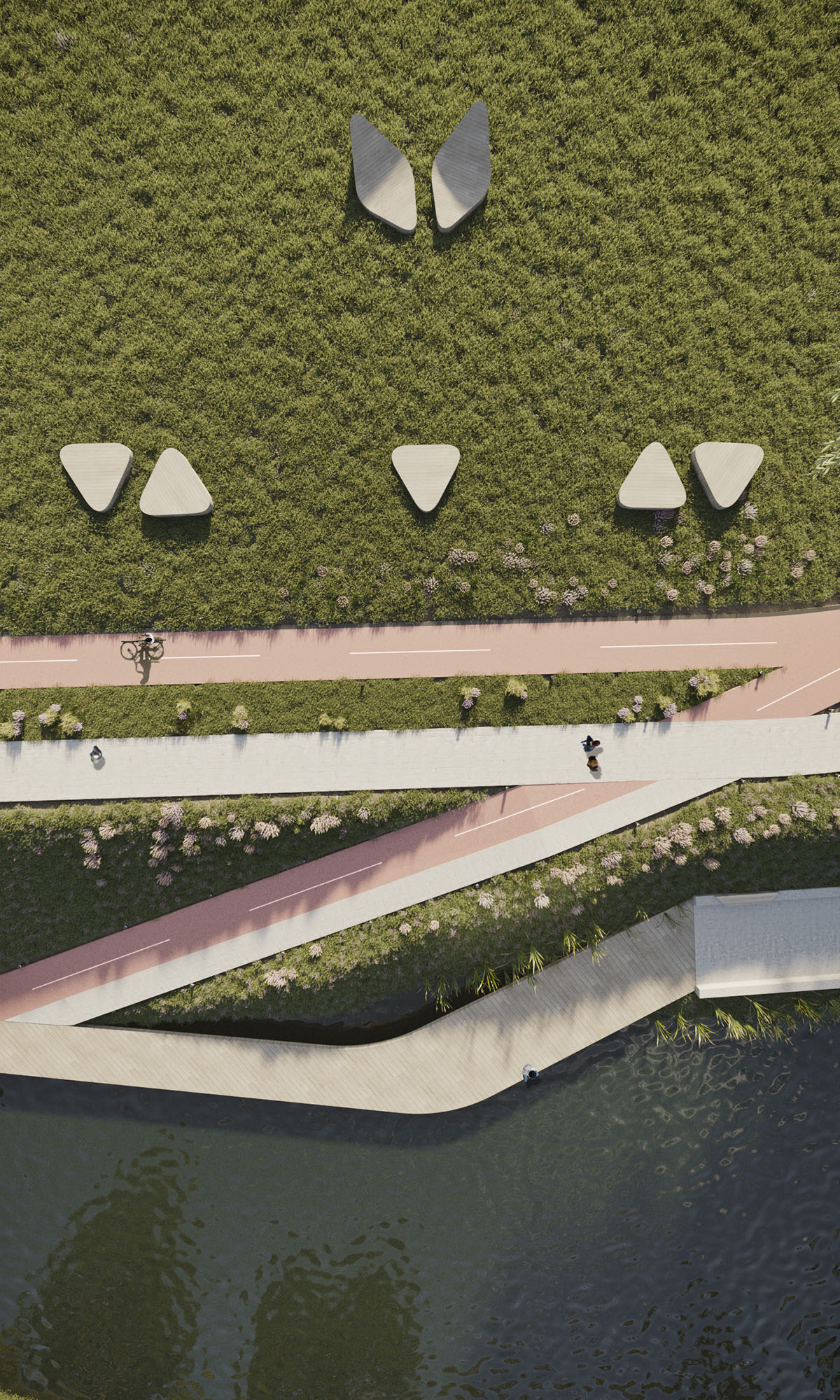

In early May, it was announced that her studio would handle the reconstruction of Chernihiv. The city besieged by the Russian forces for over a month sustained substantial damage: a few hundred buildings were destroyed, and two dozen historical and architectural landmarks required repair. Victoria saw the rebuilding of Chernihiv as an opportunity to improve the city. On the 18th of June, she presented a concept titled Chernihiv, a Sustainable City, which she and her team developed as a pro bono project. In it, they envision the post-war Chernihiv as an environmentalist paradise with cycle lanes, pedestrian hubs and air quality sensors.

In her interview for Bird in Flight, the architect talks about why Ukrainian cities need not be entrusted to foreign specialists, which colours don’t become Chernihiv, and why the green light from authorities does not equal success for the city planner.

So, you will handle the reconstruction of an entire city. Do you feel nervous?

It’s not just me — there is an entire team of us.

But you are the leader.

I don’t like putting it that way to the point that I try keeping a horizontal structure in my own company. But yeah, I’m at the helm and bear responsibility for the project on the ideological level.

The project was initiated by our studio — Yakusha Design. Our project managers oversee and moderate every activity sector, and I make sure that our overall output matches the concept.

Before the war, your studio was primarily famous for its furniture and interior designs. Now you are undertaking to create a concept for an entire city. Are you sure you can handle it?

We also do architecture, but those works of ours are not as famous as our furniture or interiors, that’s for sure. Early in my career, I worked as an architect and then as a designer, and then I came up with furniture so outstanding that it eclipsed my achievements in other fields. Still, I think as an architect and consider myself one — I have completed many architecture projects.

Anyway, we are not the only ones involved. A city development concept comprises twelve sections: economical, environmental, energy efficiency, marketing, digitalization, and more. We have engaged over 100 professionals in this work. Therefore, it would be more appropriate to ask about organizing the process. My focus currently is to involve highly-qualified specialists in this.

However, I do believe it’s detrimental to think that foreigners will come and handle everything for us. They certainly can, but the result won’t bear the Ukrainian mark anymore. The cities will lose their authenticity, their DNA. It’s this DNA that we began with.

How did you get the idea to take on the city’s reconstruction?

Many smaller architectural initiatives popped up after the war began. Everyone was running somewhere. Seeing that, I realized it wouldn’t do — it all had to be grounded in a concept of some kind.

I have extensive experience reconstructing Khrushchev-era houses — the temporary housing turned permanent with all the problems it entailed. Temporary solutions like that have an impact on the future. They need to be used with a clear understanding of where the city is headed. This is why I decided to try.

Chernihiv is a complex, large city with a long history, and you have zero experience in city reconstruction. Why try your luck with Chernihiv?

I took on the reconstruction for the city’s size and history primarily. It resonates with my values — historicity and environmental friendliness. I would have turned down a similar project for an industrial city because I wouldn’t feel it as well as Chernihiv.

Presently, I see Chernihiv primarily as a project. To understand what it is about, you need to talk to locals and hold round tables, open hearings, and polls. This is what we do, among other things.

The city council gave the green light to the development of your concept. Did the officials define any red lines you are not allowed to cross?

No. The officials even had nothing against making the central part of the city a no-vehicle zone.

The city council supported us, and the mayor said he liked the directions we were going in.

City authorities had nothing against making the central part of the city a no-vehicle zone.

Didn’t they have any comments?

They had, but those were few and mostly about safety. The mayor expected a map of bomb shelters, and we were yet to make it because we lacked information.

During our latest presentation, which was three hours long, we unloaded so much information on him that he probably needs time to digest it.

During one interview, you said a concept for the city would help prevent people from leaving it. How exactly?

The concept itself won’t, but its implementation will.

Let’s disregard the safety factor for the moment because it’s not a local but a nationwide problem. So, the next factor would be how comfortable the city is. Remote work is nothing unusual, and people now have more freedom in choosing their place of residence than ever. Therefore, if Chernihiv has all the necessary bike infrastructure, clean air, and traffic-free access to kindergartens, offices, sports clubs, and cafes within 10–15 minutes from your home, you will stay here instead of leaving.

When we interviewed architect Hiroki Matsura, he told us the general plan was an obsolete tool that provided only quantitative requirements without explaining the logic behind the city’s development, e.g., why some things should be where they are and not anywhere else. Do you agree with him?

Probably, I do.

General plans are drafted in Kyiv’s Dipromisto and then handed over to the cities, which tend to ignore them. I believe this situation is due to the documents being imposed on them without any consideration of the locals’ opinion. It’s an obsolete method — this kind of work needs to be based on grassroots efforts.

So, you don’t intend to make a general plan for Chernihiv.

We don’t. Our concept provides the groundwork for decentralizing the city and singling out its primary arteries.

Chernihiv has a general plan, which was created twenty years ago. There is also a new one that hasn’t been adopted because of the war. Since the new plan is yet to be approved, our revisions, which both the city’s chief architect and general plan authors support, can be incorporated into the document. We make no drastic changes to infrastructure, so there is no conflict.

Hiroki also said Ukrainian architects needed help from abroad for a lack of experience in contemporary city planning. Do you agree with that?

We sure need it because our domestic expertise is lacking. Where could we get it anyway, with many having little to no practical experience? Therefore, we keep in touch with renowned architect and urbanist Guy Perry — he advised those tasked with developing the UAE sometime ago.

You have just said we should do everything ourselves to preserve our cities’ DNA, haven’t you?

I’m all for interacting and against shifting responsibility.

We need foreign support, but we don’t want to shift responsibility to international professionals.

What kind of people do you have on your team?

It is 90% Chernihiv natives. They are working on such things as digitalization, architectural zoning, and environmental friendliness.

Do you have any foreigners on the team?

We have Israeli specialists advising us on the safety aspect and a Chernihiv-born American specializing in creating general plans.

How did you assemble the team?

Some were invited deliberately, and others through an open call. Also, architects approached us and offered to handle some aspect of the project all by themselves or even said they didn’t like the concept of Chernihiv as a sustainable city. I told them to go work on it by themselves. Others pursued their own pecuniary interests, and we turned them down, too.

What did they offer?

One architect said, “I suggest we do concrete benches — let’s do it”. I told him his benches didn’t fit our concept, but we are a free country, and they could develop a vision of their own. I won’t name them to avoid controversy.

Is all the work you do pro bono, and the city doesn’t pay for it?

It is.

Usually, volunteer passion wears out in a few months. Have any people left your team already?

Some have. However, we make a point of replacing people who can’t carry on.

Meanwhile, we are on the lookout for grants. It’s hard to do volunteer work for three months straight. My project managers and architects are involved in the project. They are many, and I pay their salary. Meanwhile, they don’t earn me any money working like that.

How do you keep your bureau afloat?

FAINA — our furniture brand — does. The furniture sells worldwide. We have dealerships in Australia, the USA, and China. Some orders also come from India and Brazil. Initially, Yakusha Design invested everything in FAINA, and now FAINA is our breadwinner.

Have you had any progress with your search for grants?

Some organizations do want to support us, but getting money takes time. We are looking for smaller sums for every section we do, but we didn’t even make a calculation for the project overall.

How much money does your environmental section need, for example?

I don’t know. We haven’t calculated it yet. Besides, this section can get support from European organizations, albeit they will provide specialists instead of money.

What happens if you don’t secure funding?

We will still complete the concept and hand it over to the City Hall.

What will the new Chernihiv look like if your concept gets implemented?

The city will have three primary arteries. Myru Ave. will be the first one (it’s the city’s central street). We suggest making it the city’s business hub. We will keep the market, albeit making it more organized, the reconstructed hotel, and the Shchors cinema. For a city of our size, a couple of new business centres and hotels will suffice. We will also improve amenities, make a broader road if we need it or add cycle lanes, greenery, and pavements if we don’t.

The second one will be the industrial artery consolidated around railways. It’s a sizeable chunk of the city, so we marked what could be done with the industrial facilities, albeit the details are yet to be decided on.

The Stryzhen River will be our third artery. We will set up recreational facilities and greenery along it. Initially, we wanted to launch boat traffic on it, like in Amsterdam. It would have been an excellent tourist magnet. However, environmentalist Oleksandr Usov told us it was impossible to implement the idea because the river had standing waters. It’s great we discovered it at the early stage of our work.

I read that your project provides primarily for five-storey housing. Meanwhile, Ukrainian developers build houses of at least 9 storeys. Why would you put there a requirement that will get ignored anyway?

With such proportions (the ratio between the buildings’ altitude and the width of the streets), you won’t feel as if the buildings are pressing on you. Chernihiv has a uniquely comfortable feeling of scale, and we need to preserve it.

Besides, I don’t see why we would ruin the central part of the city by putting high-rises there. Nine-storey buildings with tiny surrounding grounds are something I’m not a fan of. Why would Chernihiv residents compromise on that, having the advantage of proportionate development in relation to human height?

I get all that. However, it won’t stop developers from erecting nine-storey-high residential blocks.

I feel the community would be against it.

The community is very active in Kyiv, too, but it often can do nothing about developers. Do you think Chernihiv residents will?

I have no answer to that. Sure, people can be tricked easily, like when Kyiv developers promised to preserve some buildings but ended up demolishing them at night.

People could walk out and try to have it their way, but I don’t know for sure if they would succeed. Here, everything depends on the mayor and the developers. Hopefully, communities will become more active after the war and gain political weight.

Over 1,000 flats and 1,500 private houses were destroyed in Chernihiv. Does your plan involve changes to the city’s structure and demolishing or rebuilding housing and neighbourhoods?

The city’s outskirts have suffered the most. We offer to rebuild at least one of the city’s neighbourhoods (Bobrovytsia) in the format of a pilot project. However, it’s nothing more than a dream for now. Before we approach the authorities with that, we need to know if the City Hall will support us and find out who owns the land there. We have no time for unfounded fantasies. For this reason, we did nothing about industrial areas, either.

Imagine a perfect world where you could rebuild Chernihiv as you see fit. What would it look like?

It would be great to have an autonomous quarter with solar batteries and heat pumps. We could make it fully self-sufficient in terms of power supply. But then there is an issue of price and certification. It won’t pass the certification if we use Ukrainian materials, and the foreign ones are too expensive.

What should the architecture of Chernihiv look like?

We work on preserving architectural and historical heritage. The key efforts are aimed at highlighting it. We want to find the city’s architectural code so that we can reinvent it and integrate it into the contemporary context. That is to say, we are trying to distil the city’s colour palette, geometric shapes, and rhythm.

What kind of colour palette are we talking about?

Greens and ochreish beige shades because the city’s historic centre is all clay and brick.

Which colours don’t suit Chernihiv?

I’d say it’s blue.

But some wooden houses in Chernihiv are painted blue and violet, aren’t they?

They are, and it’s a problem for the city. Wooden houses are an important heritage, but few understand their value. People demolish them and re-paint on a whim.

What architectural forms fit the city the best?

We are talking not about forms here but rather three primary authentic styles: Ancient Rus architecture, Cossack Baroque, and Wooden Lace. They make Chernihiv stand out. Also, these styles have notable nuances, e.g., proportions and rhythm.

Do we need to make new buildings look contemporary?

We do. We are living in contemporary times, after all.

How much will it cost the city to implement your plan?

We haven’t made any estimates yet.

What you are saying sure sounds inspiring. People working as volunteers, authorities and general plan authors sharing the same vision… Is it, in fact, as idyllic as it sounds?

Not quite, because money is still the key issue. Our country is at war, and there are no resources to implement our concept. Besides, I can see politics in decision-making even now, and I can imagine somebody will sure start throwing sand in the gears when it comes to implementing it. I don’t know who it will be, and I don’t think I want to.

Then how do the “politics” manifest if you don’t know who it will be?

You ask questions I’d like to keep unanswered. All I can say is we have to compete with the interests of developers who think not about the future but about what they want now.

Is that to say that you have many difficulties but still believe that your effort is not in vain and there is a chance of this concept being implemented?

Definitely, it’s not in vain, and there is some chance of that.

We create the foundation for other architects who come to Chernihiv to build upon.

We strive to involve as many people as possible in developing our concept. The more people see it as the fruit of their own work, the fiercer they will protect it.

What scenario do you consider perfect for your concept?

The one where many different well-to-do people and organizations join the project, e.g., the Architecture Chamber. As a result, Chernihiv can become an outstanding city within 5–10 years.

And what is the most pessimistic one?

That everything gets pilfered now. I mean not only money but city space, too. They would build higher in one place, make repairs elsewhere, and quickly construct something in the third one, and everything would stay as it is. Our cities won’t have a second chance after the war.

Our cities won’t have a second chance after the war.

Presently, Chernihiv is heterogeneous, like many Ukrainian cities. It doesn’t feel its potential and suffers from an inferiority complex. People need to understand that Chernihiv is about environmental friendliness, and they can go there to recharge.

What is the probability of such scenarios unfolding?

I believe the good one is 60% likely to happen, and the probability of everything going sideways is 40%. I’m an optimist. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have agreed to this in the first place.

So, the chances are basically 50/50. I mean, the concept might remain unrealized, but you would waste your time, money, and resources of your business. Why would you need that?

As I said, I don’t want a foreigner to rebuild Chernihiv. They would be unable to capture its spirit. In the best case, they will turn it into another faceless European city.

At the architect meetings, we talk a lot about reconstructing cities after the war. Everyone knows how to do it but keeps waiting for a client to approach them. And then nothing happens.

We are doing many things for the first time now, so we have to invent solutions. This is what I do. Only time will tell if it’s right or wrong.

Viktoria Yakusha photos by Geert de Taeye

Visualizations by Yakusha Design

New and best