“Many Found the Revival of the City Surprising”: How Hiroshima Recovered from the Nuclear Bombing

On August 6, 1945, an American bomber dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima. It was the first case of nuclear weapon use in human history. Even the Americans themselves were shocked by the scope of destruction it caused. Buildings within two kilometers to the bomb explosion epicentre were destroyed by the blast wave. More remote areas, which consisted mainly of wooden houses, caught fire. About 100 thousand townspeople died from the explosion, the number of those who died from radiation sickness is still unknown.

The reconstruction of Hiroshima became a national priority for Japan, but for some time the city’s prospects were uncertain: neither officials nor residents understood the true scale of the destruction.

Tsukuba University researcher Allam Alkazei has been living in Japan for eight years, studying how the destroyed cities are brought back to life. He told Bird in Flight how devastation caused by a nuclear explosion differs from other types of devastation, how Hiroshima managed to avoid the fate of Prypiat, and what current urban planners could learn from the merchants.

I heard that Japanese society is quite closed. You were born in Syria, but you have been living in Japan for 8 years. Was it difficult to adapt?

Many people can’t blend in here in Japan due to the lack of language skills. I know Japanese, so it was not difficult for me. Besides, the multicultural environment at the university I went to also helped me to adapt.

I had an interview with the Dutch architect of Japanese origin, Hiroki Matsuura. He said that Japan has great architects but not so great urban planners. Is it true?

I guess it is.

There are a lot of famous architects in Japan, especially the modern ones. For example, Kenzo Tange, who designed the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

When you think of the world-famous Japanese urban planners, no one particularly comes to mind. Even though they do exist. For example, the father of Japanese modern urbanism, Goto Simpei, who rebuilt Tokyo after the 1923 earthquake. And Gyoji Banshoya. Having received a French education as an urban planner, he later worked in Lebanon, Syria.

Your research interests include studying how to make cities more “vital”. What does it mean?

I study urban vitality. The meaning of this term is still debated, but the urban literature associates it with the pedestrian activity and liveliness of the city. To put it simply, the urban vitality means the visibility of people in the city.

What cities can be called ‘vital’ and what aren’t?

It is difficult to call a whole city vital or listless. Even in one district there can be a street with closed shops, and another one next to it with a bunch of working cafes and people taking a rest. The authorities of Beirut, one of the three cities I studied, did a very good job of rebuilding the city center after the civil war. Despite that, the shops there are closed with lack of pedestrians. In Hiroshima, the situation is different.

So let’s talk about Hiroshima. I will open up with a traditional question. What was the city like before the war?

It was a flourishing city with a five-hundred-year history. Most of the buildings are low wooden buildings, a castle in the centre of the city. At the beginning of the 20th century, the population of Hiroshima exceeded 300,000. The city became the center of Eastern Japan. Education and industries, including the military one, developed there.

Hiroshima at the beginning of the 20th century. Photo: UB / Roger-Viollet via AFP

Which city suffered more from the bombing, Hiroshima or Nagasaki?

Hiroshima.

For the bombing of these two cities, the Americans picked up the coordinates so as to cause maximum damage. However, when flying to Nagasaki, the coordinates had to be changed due to the weather, so there was less destruction there.

What was left of Hiroshima after the bombing?

First of all, there were vast casualties among the civilian population. A third of the city residents — which is over 100,000 people — died from the explosion or its ramifications. It’s not widely known that in September 1945, a typhoon came to Hiroshima, so it also suffered a blow from nature.

Almost nothing remained of the city itself: 90% of the buildings were destroyed. Only a few concrete structures stayed intact. Now some of them have been turned into monuments of peace. The Bank of Japan branch has become a museum; the ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which was at the epicenter of the explosion, now is the Atomic Dome landmark.

I know that before the war, the city was built in such a way as to withstand earthquakes, floods and fires. Did it in any way help in case of the nuclear bombing?

What you are talking about was called firebreaks. They were strips of empty space that, in case of a fire, were supposed to stop it from spreading. The entire rows of buildings were demolished to create these breaks. At the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, you can see photos of the city’s residents taking their houses apart for that purpose. Actually, it was the main urban planning technique of wartime, with the help of which the authorities tried to prepare Hiroshima for destruction. But, unfortunately, it did not work out during the nuclear bombing.

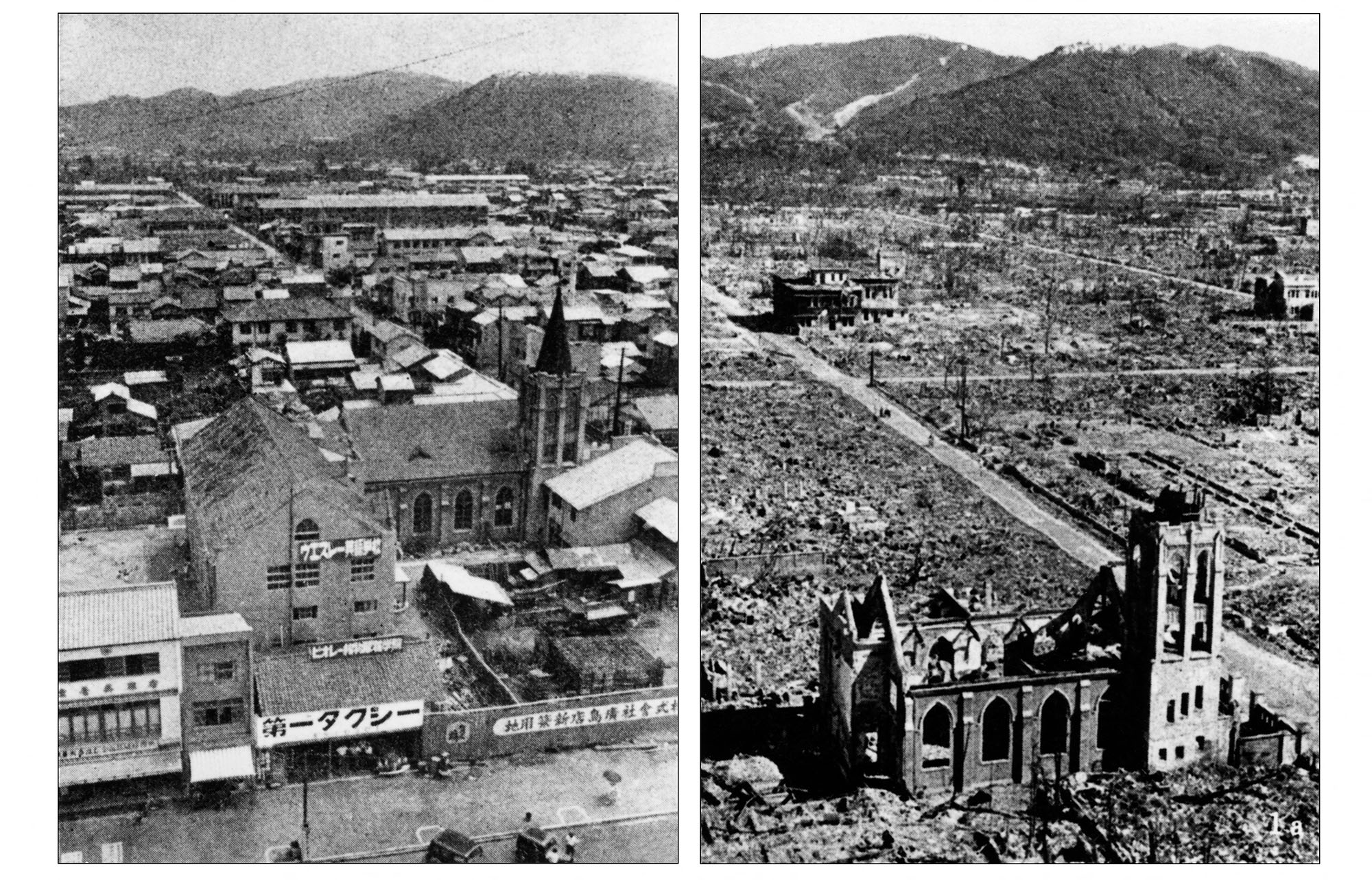

1945 Hirosima photo before and after the nuclear bombing. Credits: AFP

Why did the authorities decide to rebuild the 90% destroyed city instead of abandoning it, like it happened with, let’s say, Prypiat?

Such a decision was not made immediately.

At first, people did not know for sure what kind of bomb was dropped on them. When they finally realized it, many were sure that this was the end of Hiroshima. Someone proposed to turn the city into a “research laboratory”, others – to build around a two-kilometer radius of the epicenter of the explosion, and leave the ruins inside.

When humanity realized the full horror of the nuclear bombing, calls to rebuild Hiroshima appeared more and more often. They were followed by specific reconstruction proposals. They were based on a single idea — to create a memorial city that would remind humanity that a tragedy of this magnitude should not be repeated.

For some time after the bombing, it was believed that Hiroshima would be a nuclear wasteland for 70 years. But a year later, plants appeared there and trees began to bloom. I think this was not the only pleasant surprise. Was there anything else unexpected?

Of course. The very fact that the most destroyed city in the country was rebuilt came as a surprise to many.

The thing is that after the war Japan experienced an economic crisis, inflation was enormous. About 200 Japanese cities were damaged by the war. And Hiroshima, which was recently offered to be left abandoned, is not just being rebuilt, but is made a priority task of the country’s post-war reconstruction.

Hiroshima was offered to be left abandoned, but in the end it turned out a key task of the country’s post-war reconstruction.

Personally, I was struck by the story of one street I stumbled upon while researching Hiroshima. Hondori Street. It is located in the center and connected to the Memorial Park, the place the tourists visit first. Today, due to online shopping and shopping centers, such streets are losing popularity, but not Hondori. It is always crowded. Getting interested in it, I turned to the history of the city.

It turns out that Hondori has been around for as long as Hiroshima exists. But it is located in the city center and should have been destroyed by an explosion. Why did Hondori stayed intact? Because it was restored by the merchants.

There is nothing unusual in the fact that the locals are rebuilding the city themselves, isn’t it?

Yes, but Hiroshima is a special case. This was not a gradual destruction, but rather an instant one. It was impossible to figure out where the street used to be among the ruins.

Some residents and merchants from Hondori Street died, but those who returned there after the bombing found each other and formed an association whose task was to further reconstruction.

After the war, the city lacked the most basic things, everything cost way too much money on the black market. Despite this, the members of the association started reconstructing the shops. They financed the building of temporary shops of three and a half square meters each. Some time later, the five-hundred-meter street was no longer enough, so they organized bazaars.

Merchants understood that letting cars access the street would impede their business. So during the reconstruction plan presentation that Hiroshima and its prefecture government held for the residents, shopkeepers insisted that the commercial area should be pedestrianized. They pulled it off, Hondori still remains pedestrian.

I found the pre-war store records. Imagine: 160 shops from that street were destroyed by the bombing, 60 of them reopened in the same place and, very importantly, they did so almost immediately after the bombing. This is a huge contribution to support the life of the destroyed center of Hiroshima.

After how many years did it take to bring the city center back to life?

Trams started operating a few days after the explosion, and buildings and neighborhoods were rebuilt in a few years. So, everything happened quite quickly.

Hondori Street. Photo: Ian Trower/Robert Harding Premium/AFP

You said that Hiroshima was made a priority for the post-war country reconstruction. What were the signs of it?

At the end of 1945, the national authorities developed the basic rules of reconstruction for 115 cities. Based on these rules, local authorities started creating drafts.

In 1946, a separate law was drafted for Hiroshima, Peace Memorial City Construction Law. According to it, the national and all local authorities of the country had to contribute to the reconstruction of Hiroshima, and those responsible for the reconstruction were accountable on the work to the parliament. Besides, and this is very important, all the Hiroshima land that belonged to the army was given to the city.

For the reconstruction of Hiroshima, a separate law was drawn up on the city construction — a peace memorial.

American advisers and Australian architects were involved in the reconstruction. As a result, their plans and proposals were not implemented, but they became a part of the discussion about the future of Hiroshima.

I know there were 34 plans to rebuild the city. Which of them was implemented?

You mean ideas. But the plan was just one, drawn up by the planning departments of the prefecture and Hiroshima city. It was refined and revised until the 1960s. The project was very difficult to implement, so the authorities had to simplify it.

Who owns the idea of turning Hiroshima into a memorial city?

One of the main initiators was the mayor of Hiroshima, Shinzo Hamai. He got the go-ahead for the job from the headquarters of the Allied Occupation Forces, which oversaw large-scale projects in Japan. Then Hamai wrote the book “The Mayor of the Atomic Bomb” about the reconstruction of Hiroshima.

The editorial plan of 1952 envisaged not just a memorial, but a 12-hectare Peace Memorial Park at the very epicenter of the explosion. A lot of things were there: the

In addition to the memorial, what else did the reconstruction plan contain?

10% of the city’s area should become greenery; construction of the Peace Boulevard, which was supposed to stretch along almost the entire area of Hiroshima eastward; development of the drainage and sewerage system. Six rivers flow through the city, and their embankments also had to be green.

In addition, the plan envisaged very wide streets, both for beauty and to prevent destruction during natural disasters. The width of Peace Boulevard is 100 meters. Such parameters are rarely found in Japan.

a symbolic grave in which there are no bodies of the dead

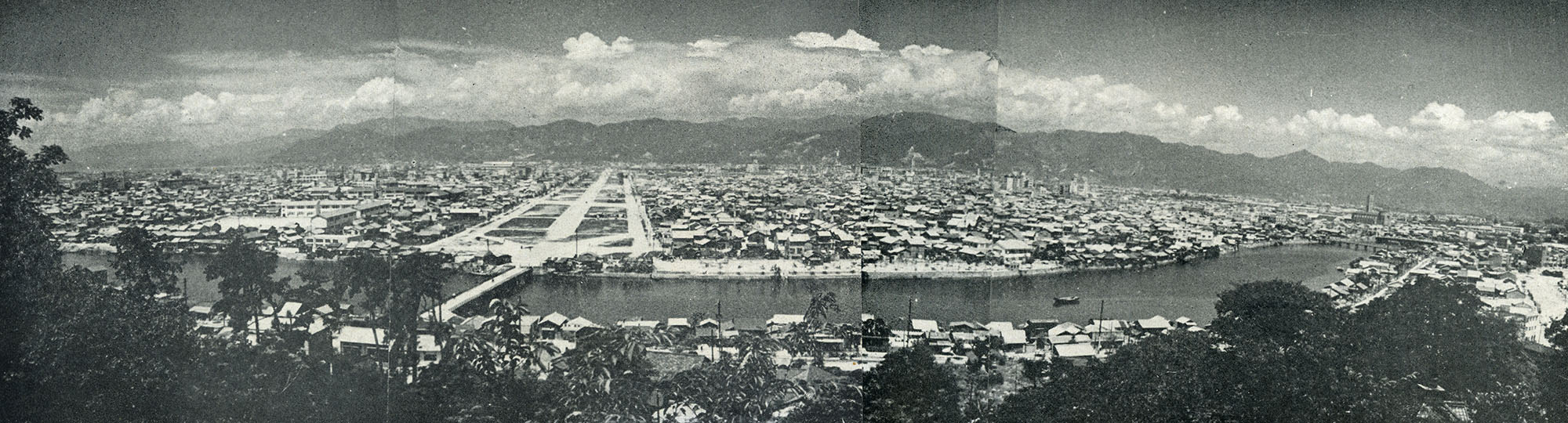

A panorama of Hiroshima in 1955, to the left you can see a hundred-meter-wide street - Miru Boulevard. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Hiroshima in 1962. 1 — the epicenter of the explosion, 2 — Peace Memorial Park, 3 — Peace Boulevard. Image: Based on National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan

Peace Memorial Museum, architect Kenzo Tange. Photo: Depositphotos

Peace Memorial Park. View of the cenotaph of the victims of the explosion and the Atomic Bomb Dome. Photo: Dimitris Argyris / Flickr

I read that, despite the special law, the authorities still had legal problems with the land. It’s true?

Yes.

In any country, land ownership is the biggest problem during the city reconstruction. Japan was no exception either.

Local urban planning uses a fundamental method of land readjustment. According to it, during the laying of water arteries and roads, every piece of land that is in private ownership is moved so that it is convenient for everyone: the owner, the city, the residents. At the same time, 10-15% of the area of private property is given over to the city infrastructure. All this happens with the consent of the owner, so the result of the reconstruction depends on the number of those who agreed to cooperate.

So, in Tokyo, for example, it was not possible to fully implement the reconstruction plan, and in the city of Nagoya, on the contrary, the percentage of consent was very high.

How did the Japanese authorities settle the issue of the citizens who were left without a home?

It was a big challenge. In order to deal with it, it was necessary to build mid-rise social housing, although it did not completely solve the problem.

In Hiroshima, to the north of the Memorial Park, a rather large area with unofficial buildings has formed. Living conditions there were poor due to vernacular construction and the risk of fires. Instead of it, the authorities created the Motomachi residential area with public housing in a modernist style, with buildings standing on columns and having green roofs.

How long did the reconstruction take and how much did it cost?

Depends on what to consider as the end.

I would say it continued until the early 1970s when the Motomachi area was finished. To date, the total cost of construction of the Peace Memorial is approximately ¥1.7 trillion ($13 billion).

View from the roof of the Sogo shopping center in 1981. This area was within a five hundred meter radius of the explosion. Photo: Roger-Viollet / AFP

How did pre-war Hiroshima differ from the post-war city?

Military objects were removed from it. On the areas of land belonging to the army, social housing, public buildings, parks were built instead. The commercial center of the city, over which the bomb exploded, was turned into a Peace Memorial Park.

In the 1950s, Hiroshima’s buildings became taller, instead of wooden structures, concrete ones appeared, tough this is the result of a global trend. Now Hiroshima looks like any other Japanese city

The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are terrible and they, fortunately, so far remain the only cases of nuclear bombing. What three architectural conclusions can be drawn from them?

I will speak mostly of Hiroshima.

Reconstruction of cities after a major destruction is often seen as an opportunity for change that would otherwise not be realized. There’s nothing wrong with that, as long as you don’t forget about the continuity.

A local does not treat the city in the same way as someone who wants to profit from it. The people in Hiroshima did not forget about it.

Comparing the structure of the city before and after the reconstruction, I noticed that despite the heavy destruction, the main streets remained on their places, although the city planners made the blocks smaller for fire safety.

So the three lessons are as follows: maintain continuity, make necessary changes, and involve all stakeholders.

During the reconstruction of cities, continuity should be maintained, necessary changes should be made, and all interested parties should be involved.

During the reconstruction of cities one should maintain continuity, make necessary changes and include all stakeholders.

And finally, our traditional question: what would you advise those architects who will rebuild Ukrainian cities?

They need to find a balance between the new and the old. Iclude people, build for people. People’s love for their city or neighborhood can be a great force for reconstruction. They are the ones who will bring life back to the cities.

The cover picture collage is based on the AFP photo

New and best