His Legacy Lives On: Why Italians Hold onto Fascist Architecture

“Fascist architecture” means the same as “Mussolini’s architecture”. Either way, it unites several styles, including rationalism — the Italian variant of modernism — Novecento, and neoclassicism, rooted in the architecture of Ancient Rome and the Renaissance. While these styles seem diametrically opposed, there are certain specificities to their Italian interpretation. Unlike other European modernists, Italian rationalists did not want to step away from historical or traditional architecture. But they believed that real architecture should rely on logic and relevance, not on facades’ decorations.

When Mussolini’s rule started, art wasn’t his top priority; yet, he believed that the state should not only support certain artists, but create conditions for artistic development in general. With that in mind, several Italian architects, who worked in different styles, received governmental support in the 1920-1930s. By the end of Mussolini’s rule, architectural styles in Italy narrowed down to monumentalism and classical forms.

Fascist architecture styles

Early fascist architecture was a part of the Novecento art trend. Translated as “twentieth century”, the name “Novecento” takes us back to the historical periods of the Renaissance (Quattrocento, Cinquecento). Margherita Sarfatti, one of the Novecento’s founders, was Mussolini’s mistress. Novecento artists promoted fascist ideas of the dictator, and architects of the 1920s and 1930s designed their buildings in neoclassical style with minimum decorations.

Italian rationalism is another trend in fascist architecture. It was represented by Gruppo 7, an association of architects, who worked from 1926 to 1932. Gruppo 7 was based on a theoretical foundation of engineering treatises of Ancient Rome and the Renaissance, which in turn relied on calculation and math proportions. This appeal to history distinguished Italian architects from their colleagues-modernists from other European countries, who strived to break the link with historic legacy. Nevertheless, their buildings looked alike: they had strict lines, simple forms, flat roofs, and no decorations.

Casa del Fascio of Como, designed by Giuseppe Terragni of Gruppo 7, 1932-1936. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Santa Maria Novella railway station in Florence. Designed by Gruppo Toscano in 1934. Mussolini personally approved the design. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Italy changed in the mid-30s, and so did its architecture. Mussolini’s imperial ambitions led to the war in Ethiopia, urging the League of Nations to respond with sanctions. Since that time, fascist architecture has become a mirror to Mussolini’s own views. Imposed restrictions played right into his hands: Italians could not import building supplies and had to use traditional domestic marble and travertine. Architecture became even more monumental, leaning toward the style of Ancient Rome, rather than modernist trends.

Over the course of Mussolini’s two decades of dictatorship, dozens of towns and thousands of residential buildings were built in Italy. Apart from them, other public places appeared, including schools, banks, universities, governmental institutions, sports objects, railway stations, postal services, and more than 5, 000 of Case del Fascio — local centers for fascist parties.

Palazzo delle Poste in Palermo, designed by Angiolo Mazzoni in 1934. Photo: Harvey Barrison / Flickr

Fabulous 1930s

The king of Italy ousted Mussolini from power in 1943, following his defeat in World War II and the despondency of his supporters. Fascist state and architecture came to an end, and the country sank into the Civil War, which lasted till 1945. Afterward, Italy started its path of recovery from two wars.

Italy never went through the denazification process, as Germany did. The fascist party was banned, but its members created a new one and called it the Italian social movement. Fascist symbols were taken off of the buildings; Case del Fascio were renamed and turned into postal services or similar institutions. Duce’s name disappeared from everywhere — Mussolini’s Forum in Rome became the Italian Forum. But the majority of buildings of that time remained.

‘Some of the fascist headquarters were demolished. But it happened mainly because the buildings were damaged by war, not because of their negative connotations. Some of Case del Fascio were turned into squats, others were occupied by communists, socialists, and their parties,’ says Dr. Lucy Maulsby, a historian of architecture.

Casa del Fascio in San-Giovanni-in-Persiceto, 1940. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

There was a period in Italian history when Italians didn’t like fascist architecture. In the 1970s and 1980s they considered it to be ugly because of its tight connection with the painful past, says art historian Pier Luigi Tucci. Yet, the new generation of art researchers view fascist architecture as an interesting object for exploration, and conservative Italians go on rallies every time someone tries to tear down Mussolini’s legacy.

Preservation of fascist buildings is more of a technical problem: a lot of them are built of concrete, and we are still researching the technologies for its conservation and restoration. Still, the Italians think that the buildings should be saved. ‘This is how unexpected alliances originate — specialists in history, artistic legacy, and restoration join forces with Mussolini’s supporters. They have the same intention to save and protect, but their reasons are quite different,’ says Maulsby.

This is how unexpected alliances originate — specialists in history, artistic legacy, and restoration join forces with Mussolini’s supporters.

The Italian Forum, designed by Enrico del Debbio and Luiggi Moretti, 1928-1938. Photo: Depositphotos

For non-Italians, the issue is more complicated. According to Maulsby, the first thing architecture researchers from other countries see is the context. ‘I’m from the US. Americans are now rethinking monuments of the Civil War and applying this view to other countries. Actually, there are several ways to look at architecture. One of them is seeing architecture as an autonomous discipline that exists on its own and quotes itself. This tradition is quite strong in Italy,’ says Maulsby.

In 2015 fashion house Fendi chose Square Colosseum as its new headquarters, causing a huge scandal. The monumental neoclassical building, called the Palace of Italian Civilization, is the most well-known in the EUR district in Rome. It was designed for the World exhibition of 1942, which was canceled due to the war. Palace walls consist of six levels of arches, making it look like the Colosseum. The building has no decorations, except for sculptures located in the ground level arches. The entire EUR district is packed with monumental buildings from the fascist era. All of them are designed in the same “naked” neoclassical style: while having classical forms they lack decorations and molding intrinsic to classicism.

The Palace of Italian Civilization, designed by Giovanni Guerrini, 1939-1953. Photo: Depositphotos

Palazzo dei Congressi, EUR district in Rome, designed by Adalberto Libera, 1938-1954. Photo: Depositphotos

Fendi’s choice was widely criticized, but according to the brand itself, Italians did not see a problem there. For Italians, the Palace represents a historical monument, rather than a fascist symbol, Tucci says. British architectural critic Owen Hatherley has another opinion. After Fendi announced the news, he made a post, saying that fascism, obviously, never goes out of fashion, and choices like that only help normalize the country’s fascist past as just another historic period. It’s hard to perceive the building neutrally, knowing that it carries Mussolini’s words, where he praised the “Italian race” before invading Ethiopia in October 1935.

Italy still has no museums dedicated to the events of 1922-1943. At some point, it was planned to create a Museum of Fascism in Casa del Fascio in Predappio, where Mussolini was born — the city still sells souvenirs with his image and fascist symbols. The idea was abandoned after long discussions — a lot of people believed, that the museum would attract neo-fascists. Now, the building designed by Arnaldo Fuzzi in 1937 is being restored to host a Documentation Center on the early twentieth century.

Casa del Fascio in Predappio, designed by Arnaldo Fuzzi, 1934-1937. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Fascist shadow on the building

Sometimes, Italians do reconsider fascist architecture. For instance, in Bolzano, neo-fascists used to gather in front of the Victory Monument and the building of the city tax service, which has a multi-figure bas-relief with Mussolini in the center. The two buildings also attracted ultra-right citizens of German origin, who viewed them as symbols of Italian oppression. The Victory Monument was created by Marcello Piacentini, one of the most famous architects of the fascist era. Being one of the first fascist monuments, the arch was supposed to mark the border between Italians and other European people. To strip the arch of its importance for the two ultra-right groups, it was turned into a museum entrance. The crypt under the arch now hosts a permanent exhibition about the city’s history during the fascist era and occupation by Nazi Germany.

The Victory Monument in Bolzano, designed by Marcello Piacentini, 1928. Photo: Depositphotos

The facade of tax service is now decorated with one of Hannah Arendt’s most famous quotes: ‘No one has the right to obey.’ The quote is written with LED lights and translated into three official languages of the region. That’s how the project’s authors, Michele Bernardi and Arnold Holzknecht, turned a fascist building into an anti-fascist one, without changing it. Neo-fascists are no longer gathering in front of the building: the quote left the supporters of authoritarian societies no chance to hide behind an I-was-just-taking-orders mask. At the same time, people didn’t want to demolish the buildings completely, and the experts responsible for solving the problem said that deconstruction will be followed by oblivion.

Bolzano tax service, designed by Guido Pelizzari, Francesco Rossi, and Luis Planter, 1939-1942. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bolzano’s case is unique. The most Mussolini-related place in Rome, the sports complex named The Italian Forum, remains untouched. Right in its center, there is an obelisk with engraved words “Mussolini Dux” — there was a plan to remove them, but public protests intervened. The Forum’s mosaics contain inscriptions about the dictator and the war in Ethiopia, illustrations of airplanes, bombs, and people with their hands raised in fascist greetings. Tucci says that no one intends to remove those elements: ‘They are treated as mosaics from Ancient Rome and are now being restored.’

Mussolini’s mosaics are treated as mosaics from Ancient Rome and are now being restored.

Attitude toward fascist legacy varies throughout Italy. ‘Some people see it as a reminder of the awful regime and others — as a reminder of the great and glorious past. And then there are people who just see a nice and useful building,’ says Maulsby. Tucci adds that Italians are mostly proud not of fascist architecture as such, but of certain significant objects: ‘90% of the buildings from the fascist era are just plain anonymous constructions.’

Mosaics with the word “Duce” and illustration of military equipment, the Italian Forum. Photo: Michael Tinkler / Flickr

Obelisk with an inscription “Mussolini Dux”, the Italian Forum in Rome. Photo: Imperial War Museum of the United Kingdom

In the autumn of 2022, Giorgia Meloni, a far-right politician, was elected as the country’s prime minister. Tucci is afraid that this election can be followed by the revival of fascist ideas and fascist architecture, as well. Hatherley shares the same opinion: in his article about Fendi he says, that it would be possible to abstract from the fascist context if this ideology was dead in Italy — but it’s not: ‘However much the architecture of the era can be interesting and attractive, its values were deeply sick. It is right that its architecture remains tainted.’

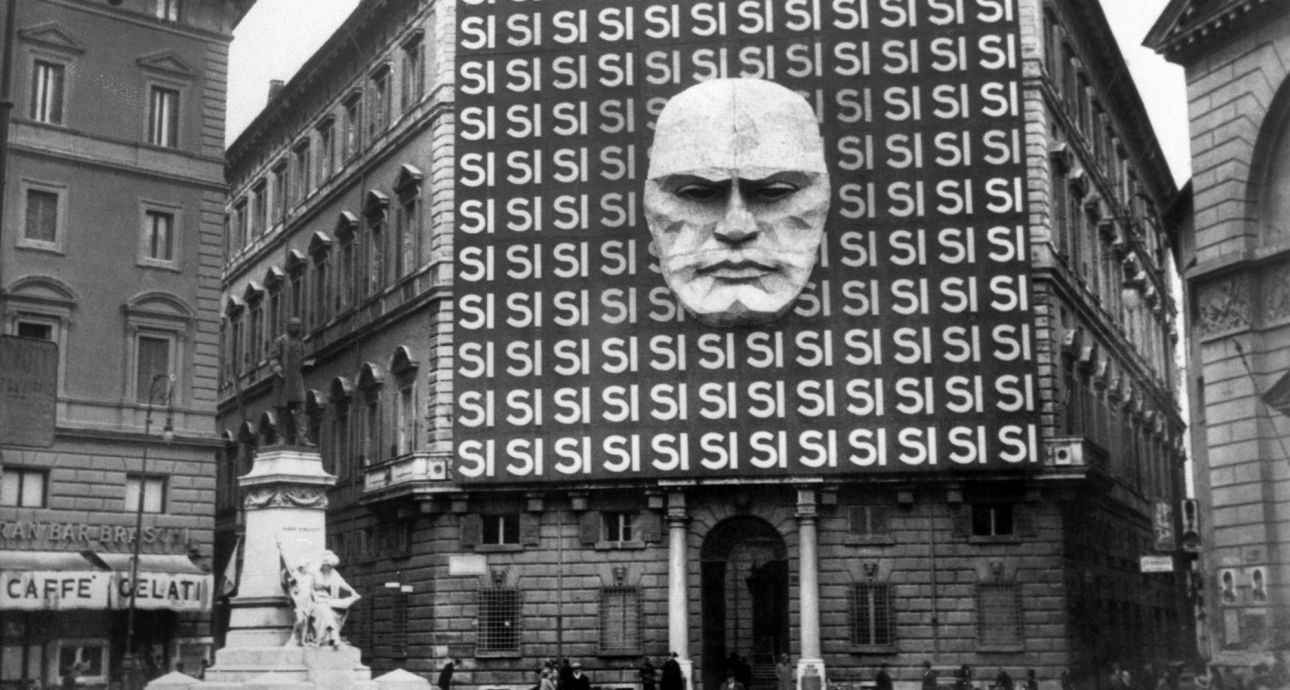

Cover photo: Headquarters of the Fascist Party in Rome, 1934. Wikimedia Commons

New and best