“Authorship May be One of the Least Exciting Aspects of Photography”: Bird in Flight Prize ‘21 Jury Member David Campany

The title of Campany’s 2020 book refers us to Susan Sontag’s book On Photography. When David was a student, he met Sontag and questioned her assessment of photography. She kindly suggested that Campany write his own book on this topic one day, which he did. David Campany talks about this book, his research, and the stories behind the pictures.

Curator, writer, and Managing Director of Programs at the International Center of Photography [USA]. David has worked with institutions including MoMA New York, Tate Modern, Whitechapel Gallery London, Centre Pompidou, ParisPhoto, and has curated many projects worldwide. He has published several books on photography, cinema, and art, and over a hundred essays.

As a writer, curator, and editor of photobooks, what methods do you use in your projects?

I would say that what is common to all of my activities is editing. My projects take shape through the editing process – whether it is a book of essays, a photobook, or an exhibition. It is through editing that relations are formed or suggested between elements. Of course, the nature of the material and the context’s specifics determine how each project is edited. A project often begins as a loose set of fragments – thoughts, images, words, paragraphs – that don’t seem to mean much, or their meaning seems hidden and obscure. That’s where the editing begins. Often there is a lot of experimentation, trying things out to see if they work together or resonate somehow. Sometimes, shaping a project happens very fast; other projects may take a year or more. I’ve found that I can’t really speed up the process. Each project has its own rhythm.

I am not sure I would call editing a “method,” though. Most of the time, it feels more intuitive than methodical, at least at first. It becomes more conscious as the process refines itself.

It seems that you are one of the rare professionals trying to take photography beyond its traditional boundaries. Why do you think it’s important?

What has always fascinated me about photography is the range of different audiences and contexts it has had almost from its beginnings. Photography falls into specialisms and functions very quickly, which can be a problem, so in the books and exhibitions I work on, I try to keep the door open to new audiences, looking for the overlaps. This is always a challenge because the tendency in the 21st-century culture has been towards bubbles of one kind or another. But photography is probably the best medium for pricking those bubbles and crossing those cultural boundaries. I am attracted to projects where I don’t know in advance what the audience or the reception will be. It’s in those areas that culture is at its most interesting and least predictable.

In the 21st-century culture has been towards bubbles of one kind or another. But photography is probably the best medium for pricking those bubbles and crossing those cultural boundaries.

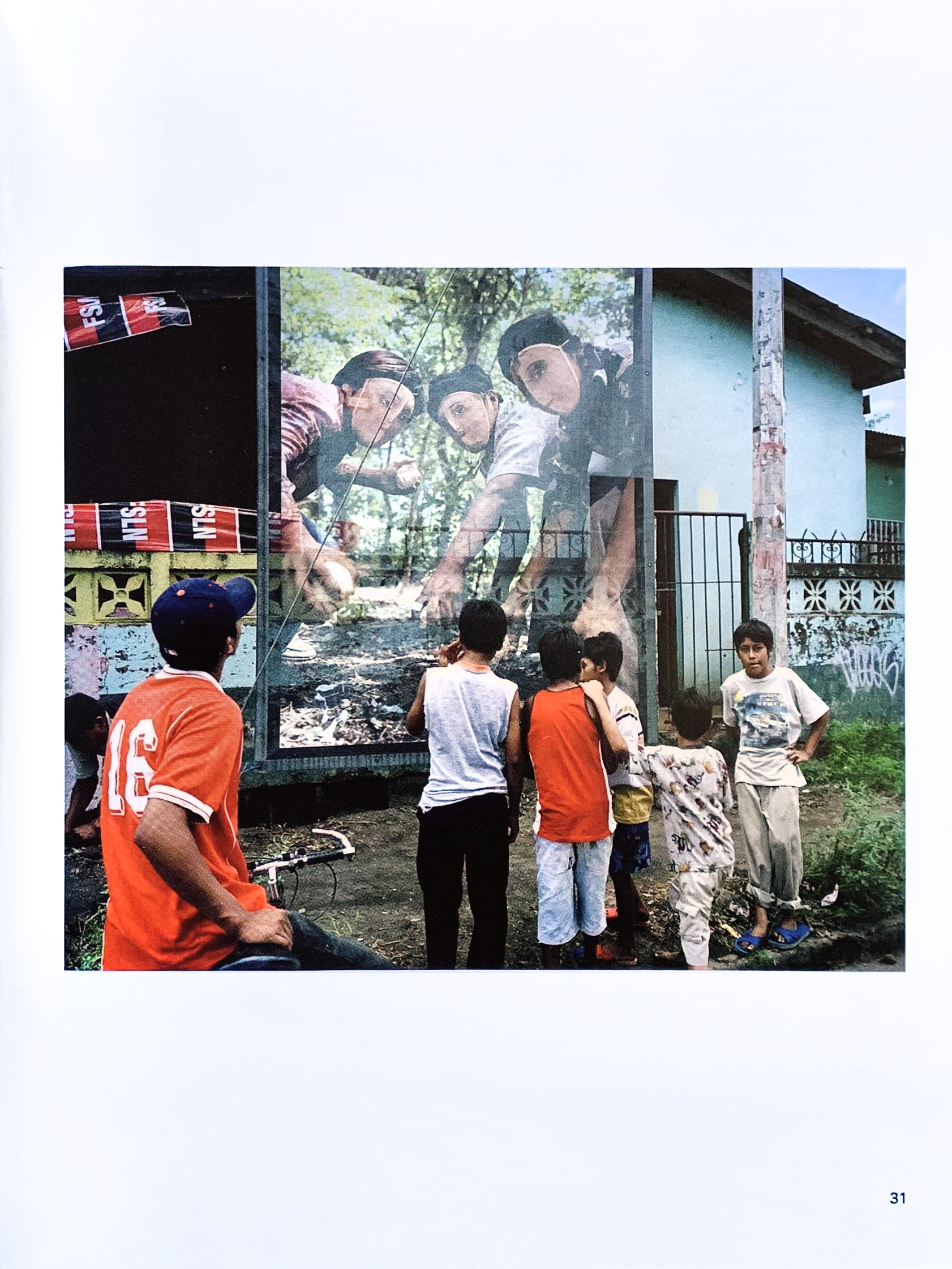

A page from the book On Photographs by David Campany. Photo: Susan Meiselas. Monimbo, Nicaragua, July 2004, from the series Re-Framing History, 2005 The American photographer Susan Meiselas began her association with the Magnum Photos agency in 1976. In 1978, she traveled to Nicaragua to document the uprising against the dictatorship of the Somoza family. Meiselas stayed there much longer than most other photojournalists, getting to know people and the situation. For about a year, Susan sent her exposed rolls of film and written notes and captions to the Magnum office in New York. On her return, she saw how various international magazines had used her photographs, sometimes in ways she was not expecting. In 1981, Meiselas made a book of her Nicaragua work. This gave her more control over her images and gave her project greater longevity. In addition, Meiselas curated exhibitions that placed pages from the aforementioned magazines alongside spreads from her book. One of Meisela’s best known images shows three people in a forest with their faces covered by traditional dance masks. These people were making bombs in preparation for the revolution. This image made the cover of several publications, including the New York Times Magazine. Over time, the photograph developed a life of its own, with varied meanings. This example illustrates how photographers cannot always regulate the use of their images.

You chose to organize your recent book On Photographs not so much around names, as it happens in most photography books, but rather around particular images, some of them even made by unknown authors. Why is that?

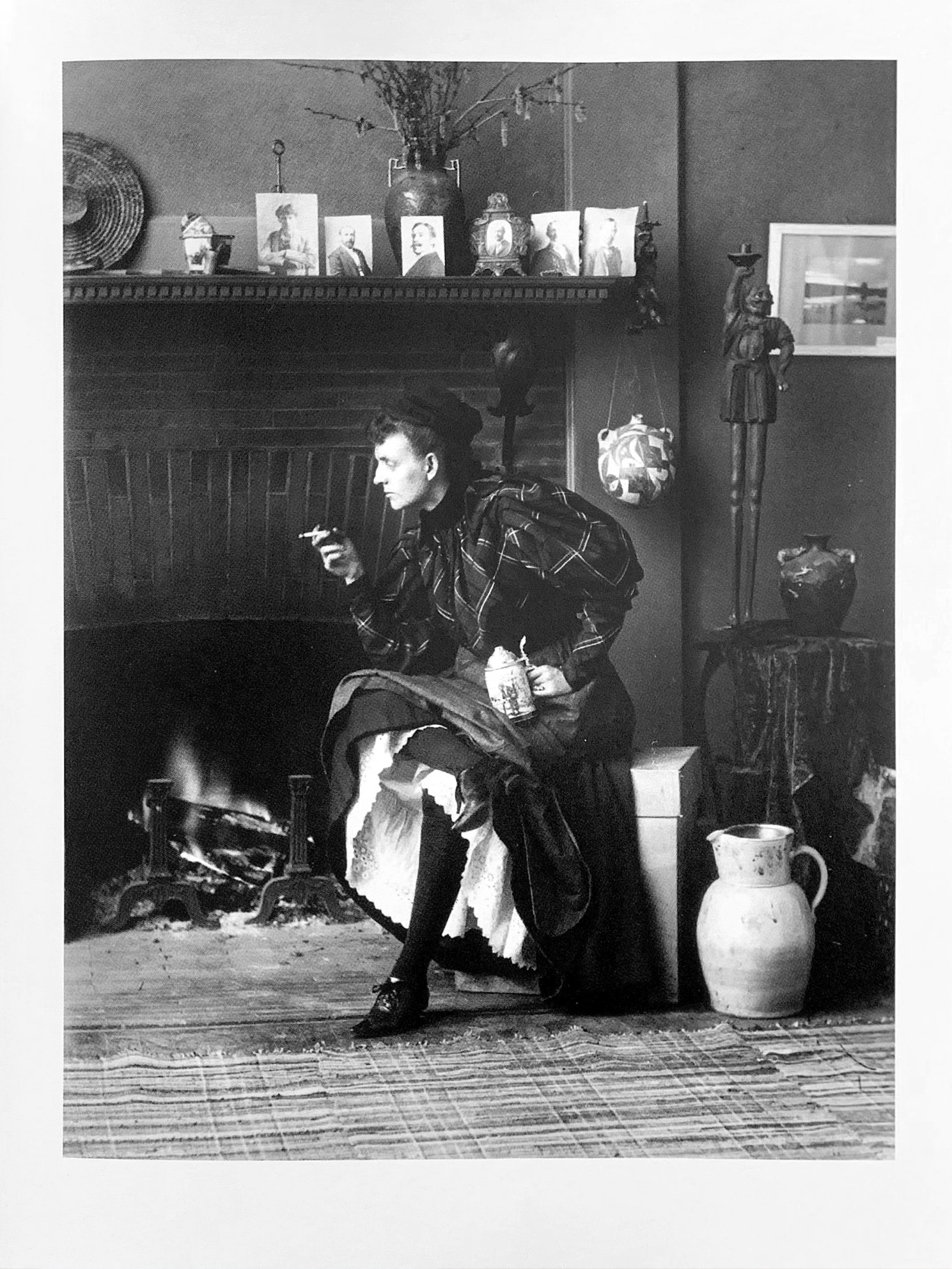

In the case of On Photographs, this was quite deliberate. The project includes images by well-known photographers, little-known photographers, and photographers whose names have been lost. This was done partly to move away from the traditional idea of “Great Photographers,” whose names we are all supposed to know, and suggest that authorship may be one of the least exciting aspects of photography. Most people don’t care who made an image, and actually, the viewer is much freer to respond for themselves if they are not overburdened by the baggage that is often attached to a name. If you don’t follow the names or the money, you end up with a much more dynamic and possibly emancipatory view of photography.

Most people don’t care who made an image.

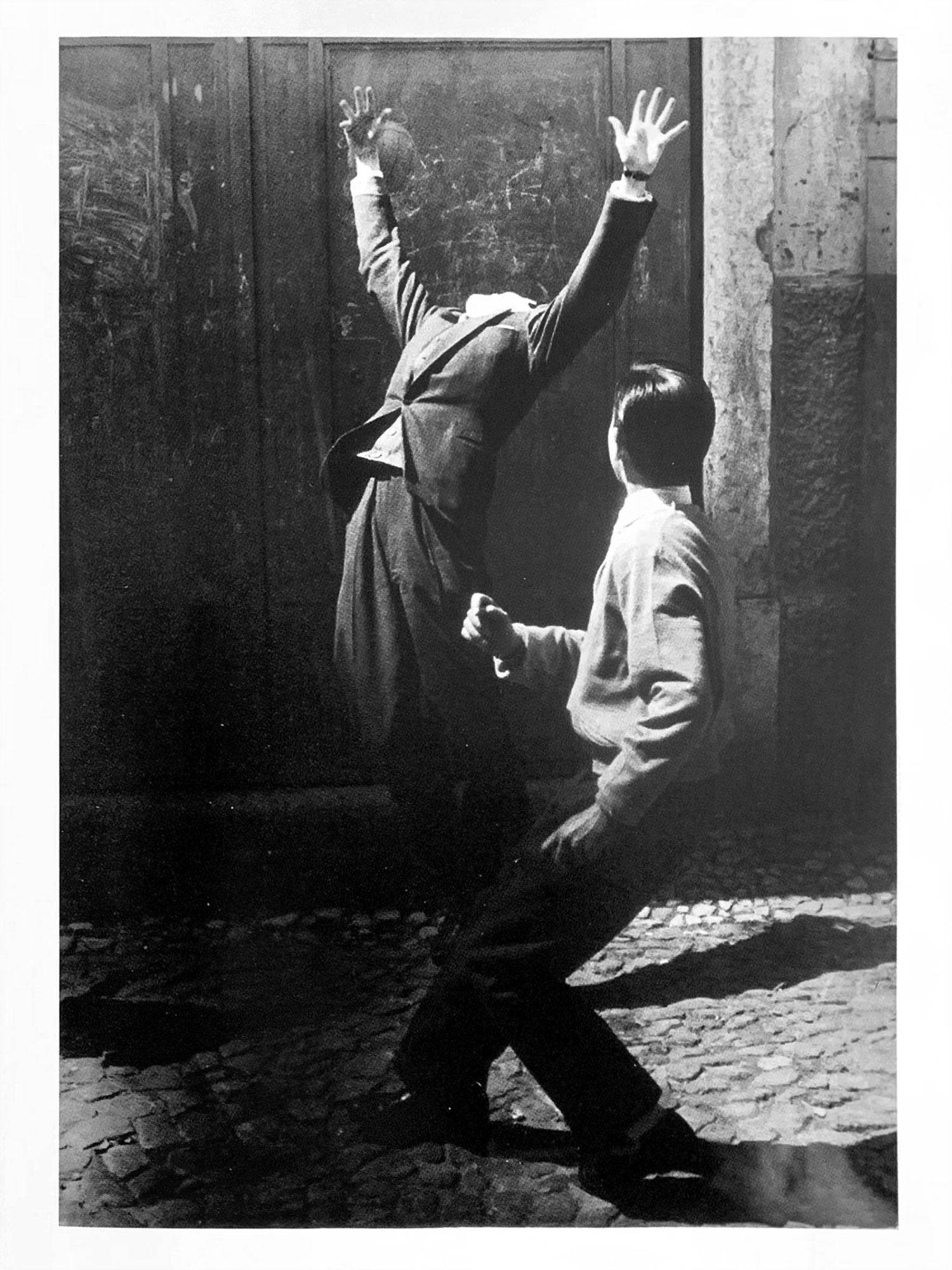

A page from the book On Photographs by David Campany. Photo: Gérard Castello-Lopes, Lisbon, 1957 The work of Castello-Lopes is little known outside Portugal. He belonged to a loose group of photographers who made remarkable images in the 50s but then he was forgotten. In this photograph, Castello-Lopes captured a moment of action. One could think that the person in the jacket is pretending to be shot, but the ball behind his right hand tells us that, most likely, he is a goalkeeper in a street game. The photograph came to wider attention when it was featured on the cover of an English-language edition of The Book of Disquiet by the celebrated Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa. At first, the image appears to have little to do with the book; however, there are intriguing parallels. Just like a group of photographs, Pessoa’s book is a selection of vivid but enigmatic fragments that can be appreciated in almost any order. In addition, the writer certainly had a deep interest in the poetry of the street. Castello-Lopes's deep inspiration had been the work of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose book The Decisive Moment had been published in 1952. This photograph could easily be mistaken for one by the French master. It is not strange: many photographers will admit to imitating those they admire. However, this raises another question: if you produce a work of art while pretending to be someone else, who made it? Is authorship ever completely free of influence? In art, we expect authors to be unique; in photography, especially, this is rare.

A page from the book On Photographs by David Campany. Photo: Susan Meiselas. Monimbo, Nicaragua, July 2004, from the series Re-Framing History, 2005 The American photographer Susan Meiselas began her association with the Magnum Photos agency in 1976. In 1978, she traveled to Nicaragua to document the uprising against the dictatorship of the Somoza family. Meiselas stayed there much longer than most other photojournalists, getting to know people and the situation. For about a year, Susan sent her exposed rolls of film and written notes and captions to the Magnum office in New York. On her return, she saw how various international magazines had used her photographs, sometimes in ways she was not expecting. In 1981, Meiselas made a book of her Nicaragua work. This gave her more control over her images and gave her project greater longevity. In addition, Meiselas curated exhibitions that placed pages from the aforementioned magazines alongside spreads from her book. One of Meisela’s best known images shows three people in a forest with their faces covered by traditional dance masks. These people were making bombs in preparation for the revolution. This image made the cover of several publications, including the New York Times Magazine. Over time, the photograph developed a life of its own, with varied meanings. This example illustrates how photographers cannot always regulate the use of their images.

All the images are taken from the book On Photographs and published with the permission of its author David Campany.

New and best