Idea-driven: How Ukrainian Creative Professionals Help During the War

The Brief: Prevent the WW3

It is literally a brief for creative professionals around the world. It aims to encourage people to launch projects focused on preventing World War 3 and raise awareness about Ukraine.

Creative group head, the project co-author

— I got the idea in the first days of the war. The project took just 12 hours to launch: its landing page was completed by evening. The brief was created to achieve a strategic goal — focusing the Ukrainian creative professionals’ disparate efforts to make all kinds of things, like banners, messages, and more. We needed a focus, so strategist Andrii Mishchenko and I formulated four communication goals. Naturally, they were amended many times later. For instance, everyone urged NATO to close the skies over Ukraine at first. A few weeks later, though, it became clear that nothing of the sort would happen, and it was more efficient to focus on arming Ukraine.

Once we finished shaping our goals, copywriter Yulia Ivakina said: “Hey, it looks like a brief. We have an objective. We have a client — Ukraine. And we have clear-cut tasks”. We realized that we could multiply the efforts of Ukrainian creative professionals if we literally “briefed” the global community. We would provide them with a strategy guide and, more importantly, remind them that creatives can and should help.

Our brief made it into one of the largest creative industry publications — Adweek — and the Miami Ad School CEO disseminated it among the school’s students and partners. Also, many Western creative professionals shared it on LinkedIn.

We have received over 100 emails with suggestions from designers and copywriters. At that moment, we realized that the brief needed to specify that it was not a contest but a call to action. We do appreciate every suggestion, but we believe the authors themselves have to launch the campaigns.

A chief creative officer from San Francisco, whose family lived in Kyiv at the time, suggested launching an alcoholic beverage under the Molotov Cocktail brand. We hinted that Bandera Smoothie was a more appropriate naming to differentiate from the Soviet era. As far as I know, the idea went into production. The authors of .PNG Protests, put the factual information about the events in Ukraine in the metadata of images of smiling Putin. Right-clicking on the image, everyone can see the text about the war crimes committed in Ukraine in the file’s properties.

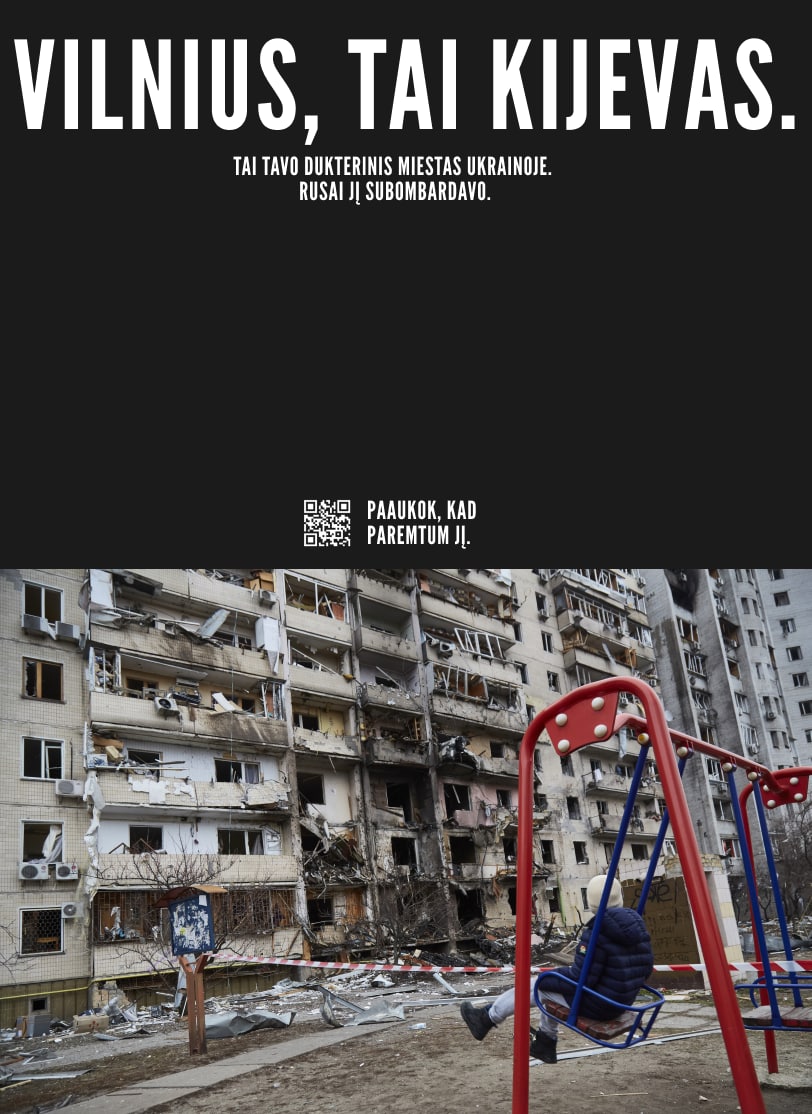

Another author approached us for help with an idea for a billboard in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which he wanted to put up to help Ukraine. Serhii Malyk, the Creative Director of the ANGRY marketing agency, noticed that Milwaukee is a sister city of Irpin, which made headlines at the time. Therefore, we wrote that Irpin was Milwaukee’s sister city and needed help, added a QR Code for donations, and that was it. The billboard was accepted without revisions.

The following week, we were invited to Lead Balloon an American podcast about marketing. Its host turned out to be a Milwaukee native and worked with the city administration. He promised us to pass the billboard idea along. After the podcast episode we were invited on was released, the editor of Milwaukee Independent contacted us to write a big story. Then we decided to scale the idea and started contacting the administrations of the sister cities of the Ukrainian cities damaged by the war. Lithuania and Poland have already joined in; Latvia and Slovakia are the next to follow.

There have been few implementations of the campaign, but they hit hard. For instance, I was contacted by a van vendor from South Carolina who said he wanted to join the campaign. We create a visual with a photo of Mariupol and the tagline “South Carolina, South Ukraine needs your support after Russian attack.”

Never Again Gallery

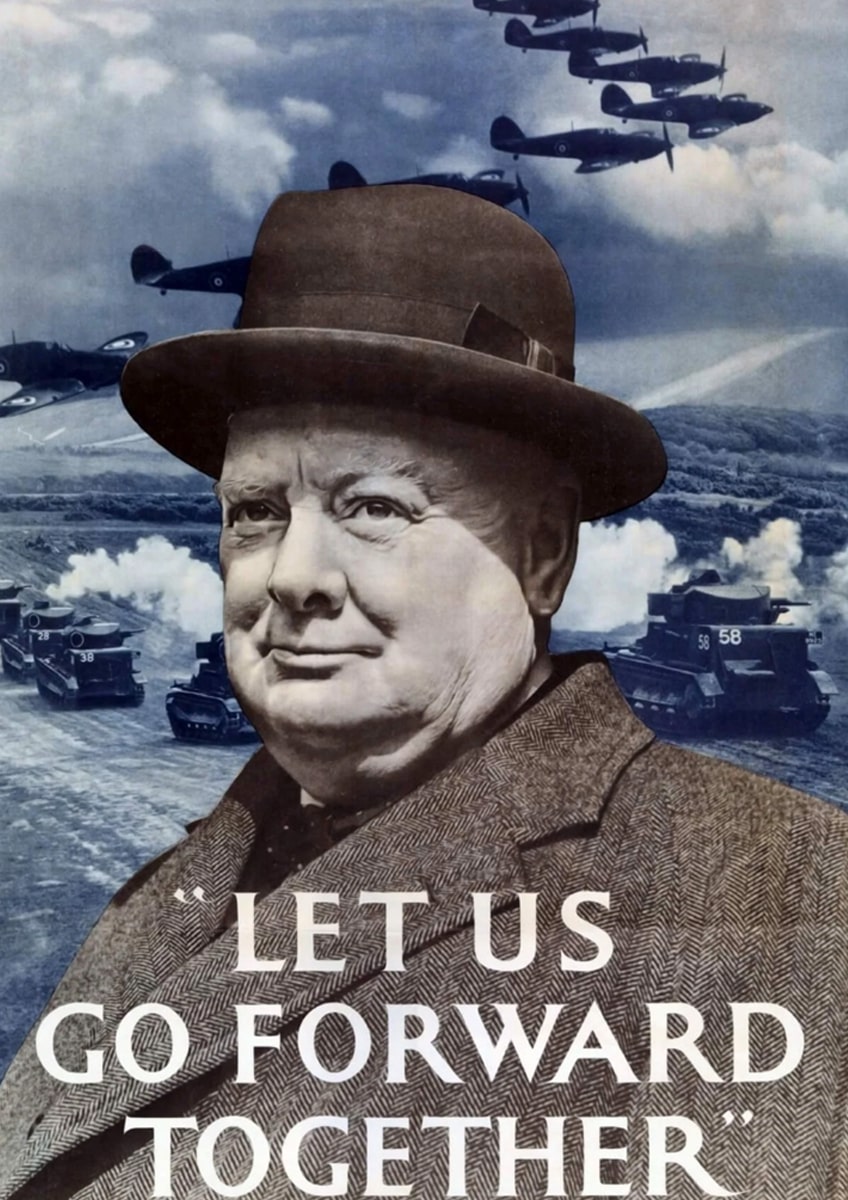

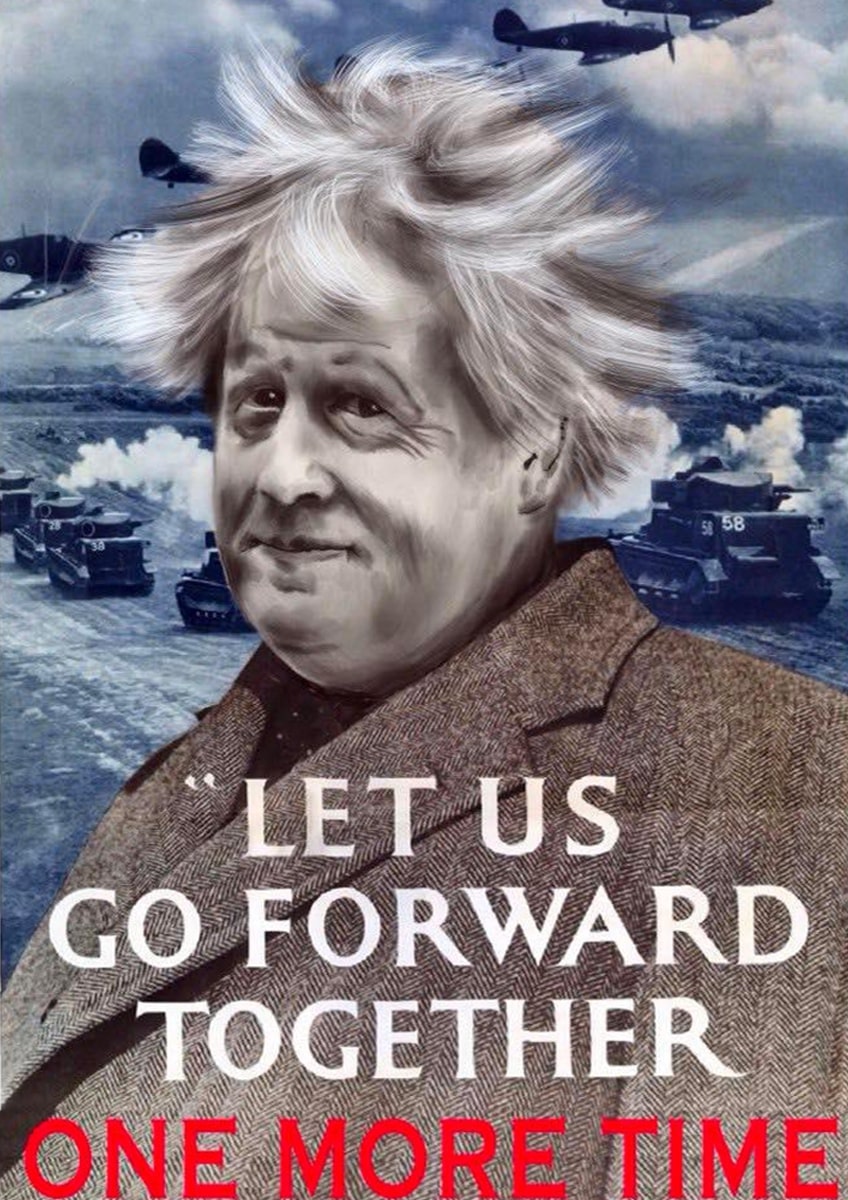

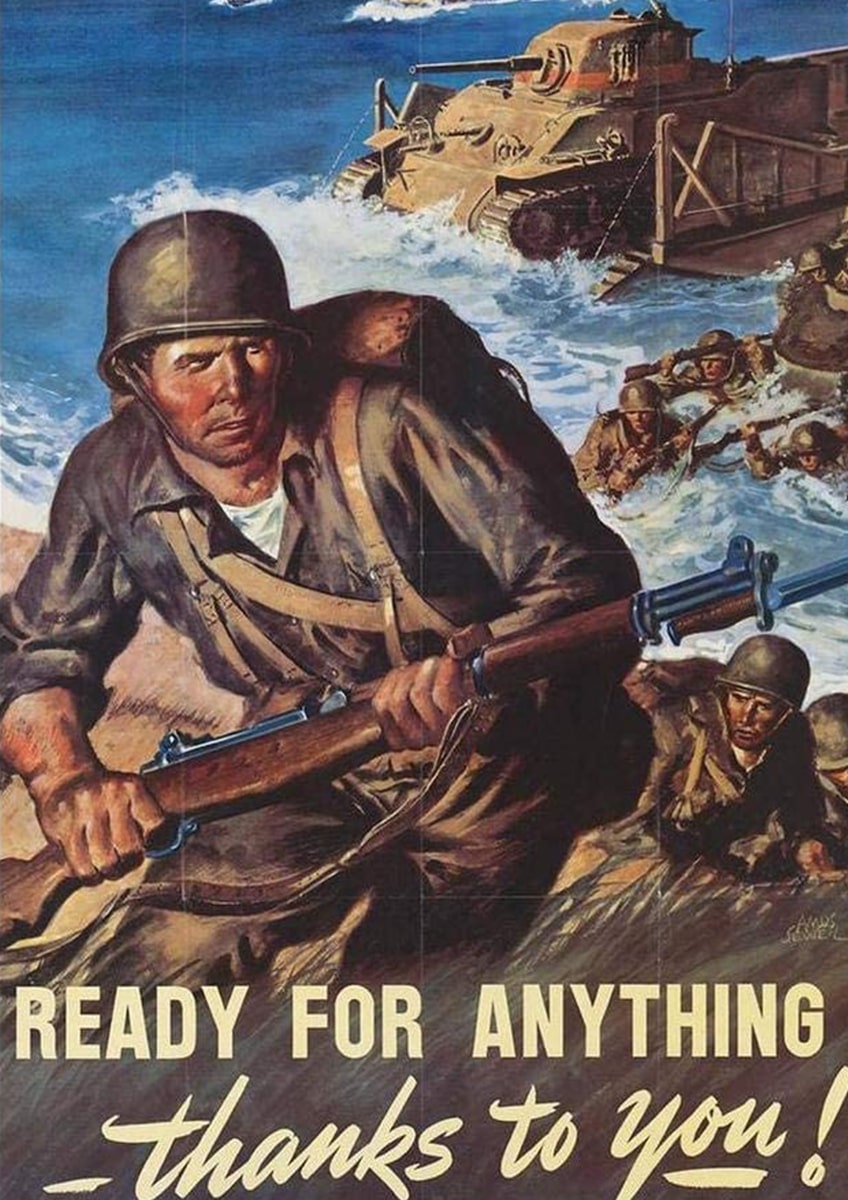

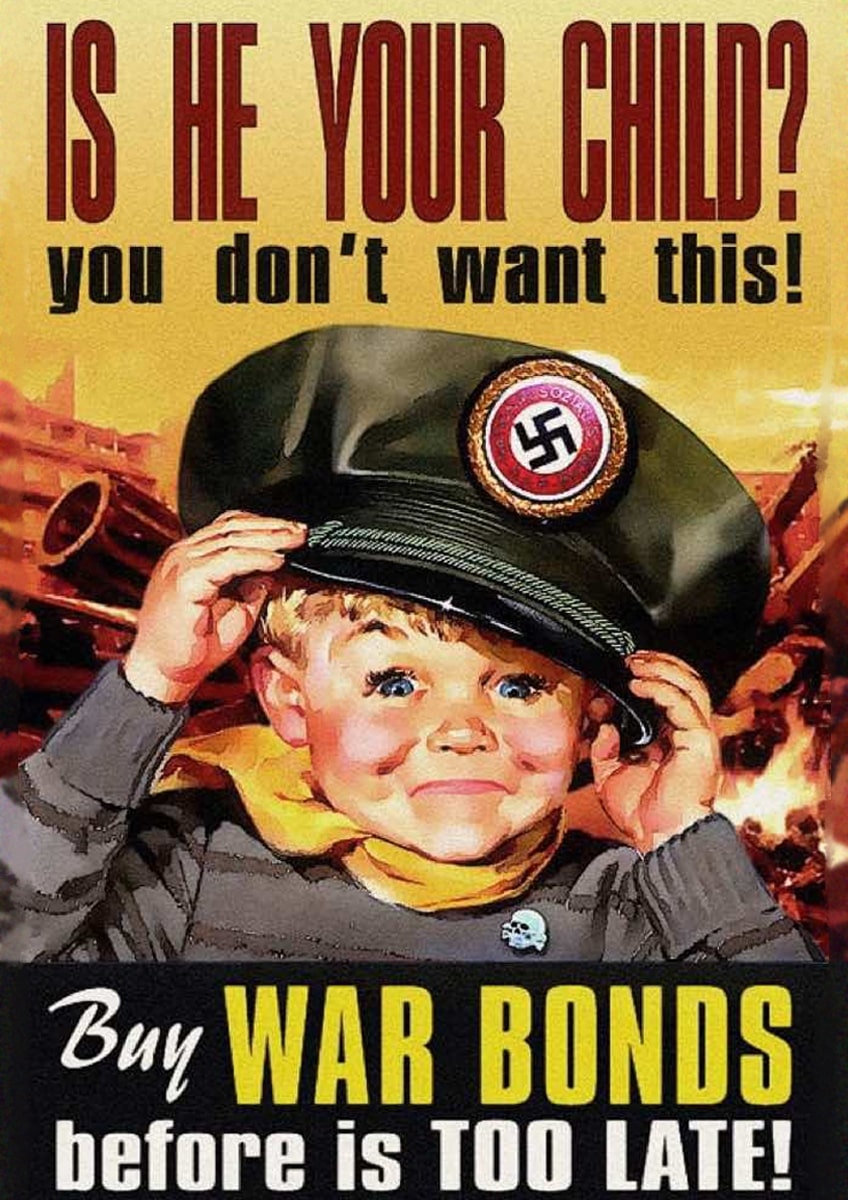

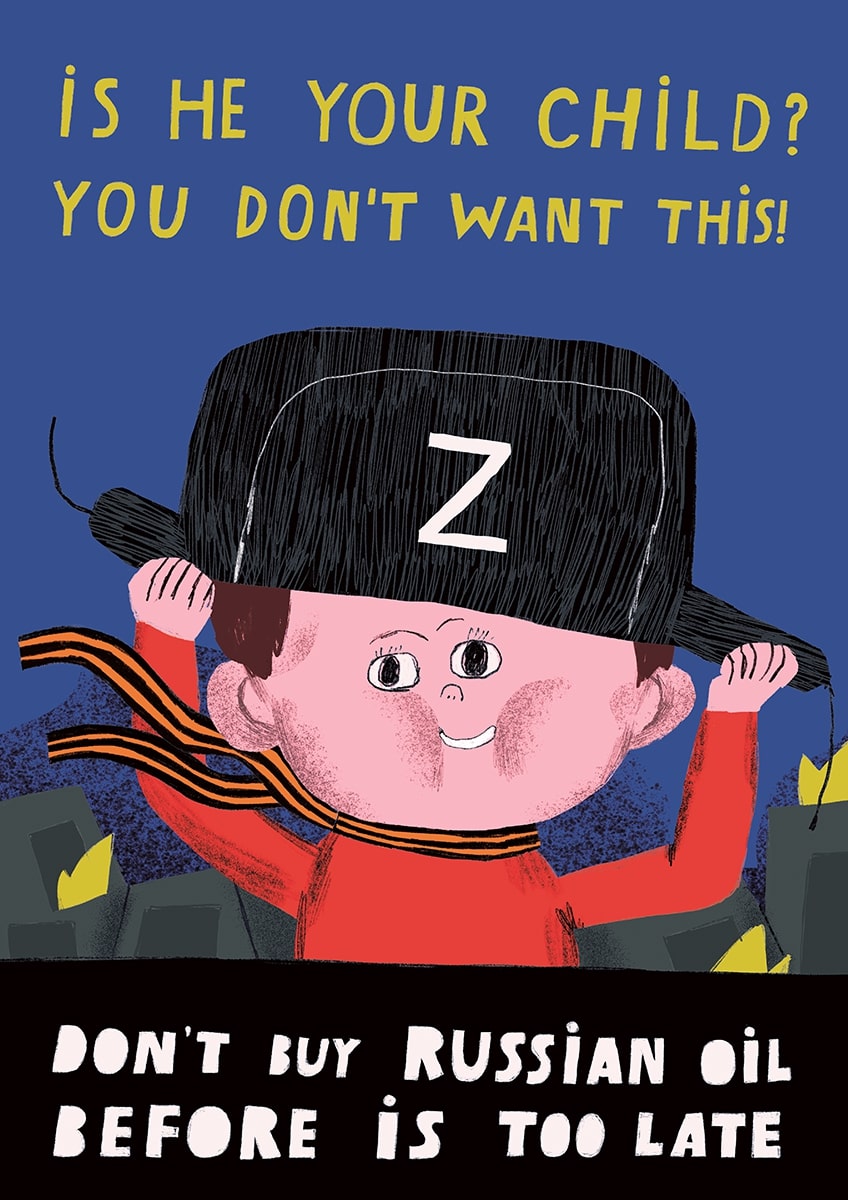

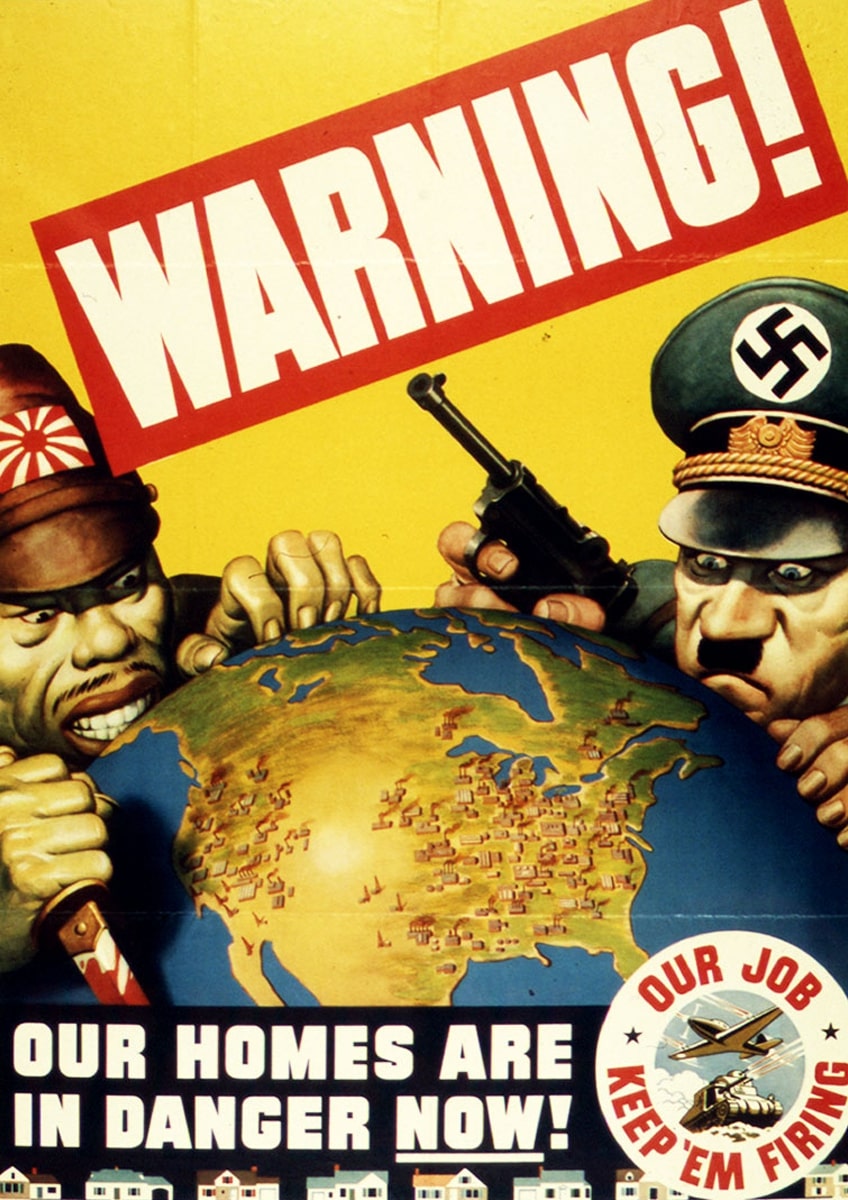

Nowadays, YouTube channels, TV, and memes have replaced agitprop leaflets and posters. Never Again Gallery imagines what the posters with Ukrainian soldiers and Russian invaders could look like.

The project’s manager

— Copywriters Oksana Honchar and Serhii Malyk came up with the project, and it took about three weeks to implement. We have gathered the posters of the World War 2 era, made arrangements with illustrators, and developed the website. Twenty Ukrainian artists and illustrators worked on re-envisioning those posters.

In 1939–1945, hundreds of inspirational posters were created in the Anti-Hitler Coalition countries (the UK and the USA specifically). Those called to action, instructed, and motivated. The USSR posters were intentionally avoided in this project.

We are currently promoting our product and see if we can organize or participate in the international exhibition. We want to remind the Western countries they were once brave and united in the face of a common enemy — Nazi Germany. Never Again Gallery appeals to historical memory, urging the Western people to support Ukraine in a situation that is very much reminiscent of what happened 80 years ago.

Over 50,000 people visited the project’s website in the first week after its launch. We put no direct fundraising messages there because our primary goal is to inform. Still, we do tell how people can help, too.

KINODOPOMOHA

“If the tapping of falling apples doesn’t remind you of rifle fire, you have never been to war.” “If the rumble of dumpster hit against the bin wagon doesn’t remind you of a shell explosion, you don’t know what the war is.” This is how the videos of KINODOPOMOHA — an alliance of filmmakers documenting the war in Ukraine — begin. Among the videos are Kyiv bombing chronicles, video reports from the Territorial Defence Force drills, a video about Mykolaiv’s resistance, and a dozen clips from the front-line areas.

Project participants’ names are kept secret for their safety

— We expected an escalation of some kind and created a filmmaker chat for information exchange two days before the invasion began. We already had a plan when it started. Then we focused on getting equipment, filming accreditation, coordinating with the military, and exchanging our experience on the new realities of filming and safety tips.

Essentially, we helped filmmakers do what they do the best — document the events. Also, we decided to put together our own videos reflecting on what we saw on the same day — this is how our YouTube channel came to be.

From the very beginning, we started accumulating a lot of footage and made every effort to share it with international mass media because there were few international reporters in Ukraine at the time. This is how we exchanged experience with Western reporters since their war reporters were much better prepared to film under war conditions. We were brought up to speed quickly, too. Our work doesn’t overlap what they do because we often film in a very different way. We do whatever we can to help them — their work makes it in the news much faster, showing the horrors of the war to the world and stimulating weapon and humanitarian aid supply to Ukraine.

We keep in touch with the military, Territorial Defence Forces, and police and monitor news and social media. At times, the final videos are edited together from the footage provided by multiple teams.

The core of our YouTube audience is in Ukraine (54%) and the rest in Poland (7%), Germany (5%), the USA (5%), and Russia (3%). We have no dedicated social media pages for the project, so our videos are disseminated via the pages of our friends and colleagues.

For now, we are planning to keep accumulating footage and edit it into short stories. Also, some footage we have can’t be used until after the war. The filming of some stories is still in progress because we follow the lives of the people we meet and wait for what comes next for them.

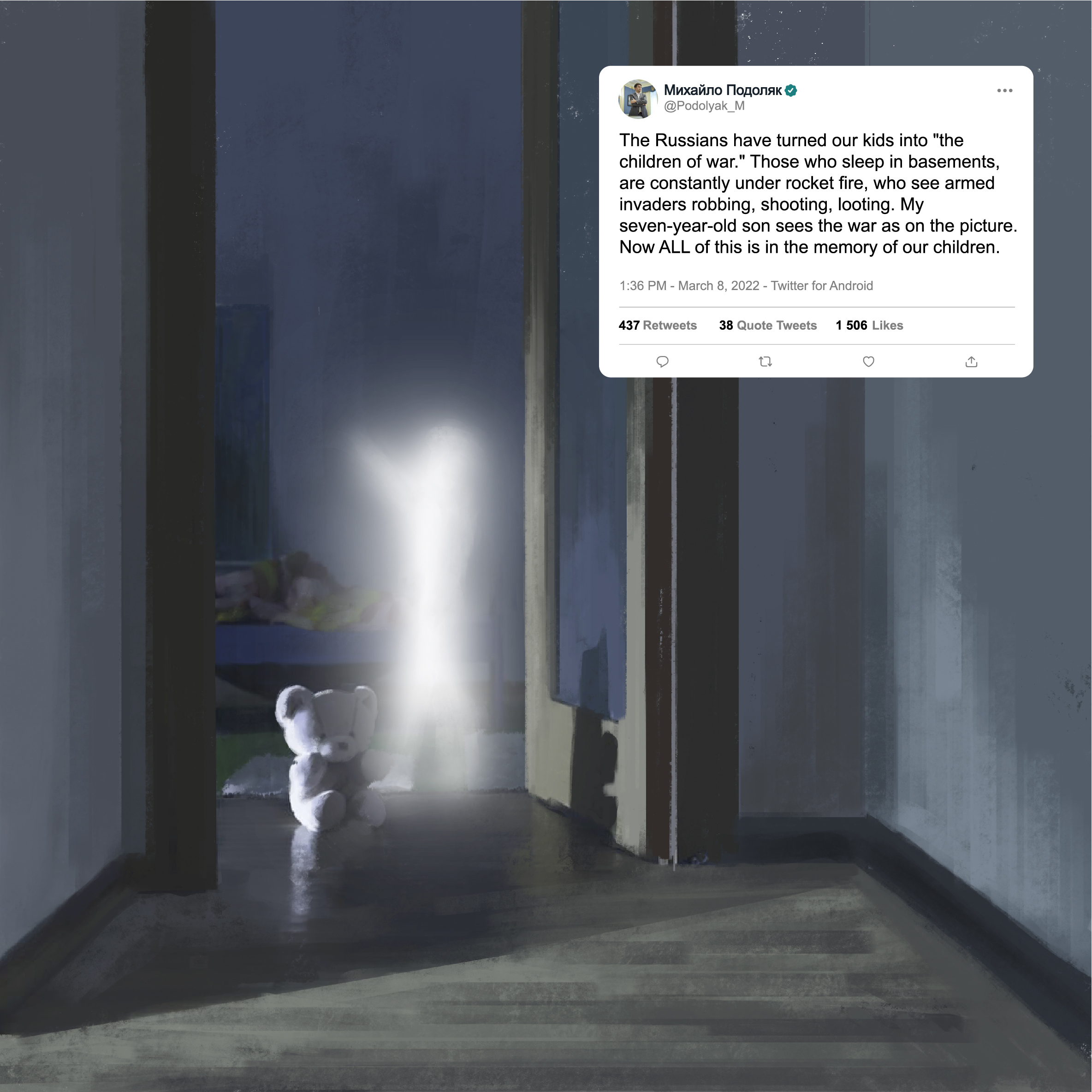

Meta History Museum of War

In times of peace, Meta History focused on crypto. However, the Russian invasion prompted it to create an NFT museum doubling as a war chronicle. The proceeds from the purchase of drops there are directed to help the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. Its NFT drops comprise the officials’ posts about the war and illustrations for them created by Ukrainian artists.

The project’s artist manager

— The project has two main objectives: to preserve the memory of the actual events of the Russo-Ukrainian war and raise as much money as possible from the global digital community. Therefore, Meta History is not just an NFT collection or trading platform but a blockchain-based historical record. The technology makes it impossible to replace, delete, or edit the events added to the collection because all the pieces in the museum are numbered and have a precise chronology.

We don’t restrict artists in their vision — there are almost no rules for illustrating the news posts. Besides, many art pieces were made in bomb shelters to the sounds of air raid sirens and explosions.

“Kyiv city authorities urge residents of high-rise blocks of flats to check their roofs for markings and cover them with dirt or anything else if you find any! They allegedly show the path for enemy warplanes to strike at critical installations.”

The war has united the people of Ukraine, so it was reasonably easy to assemble a team. We set up a group on Telegram and added the people we knew. In turn, they added their friends. Those were artists, marketers, developers, and people with all kinds of backgrounds, whether they had experience or not.

The sales of the first 100 images were launched about a month later. Now, the core of our team is 13 people, and there are many helpers, too. Nearly 150 artists have contributed to the project. Also, there is a limit to the number of pieces each can produce, so the artworks are always different. The only money invested into the project was to get 1,000 followers on its Twitter account in the very beginning. The first drop includes 99 news art pieces, 22 units each, another 4 to be auctioned, and 11 one-off illustrations made as a collaboration with Prospect100.

All proceeds from the NFT sales go directly to the crypto wallets of the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine. Later, the money will be distributed between humanitarian aid and the restoration of Ukrainian cultural heritage sites jointly with the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. The NFT owners will be able to vote on how the money is spent on the restoration of cultural heritage sites.

“Two friends — and four fewer enemy vehicles. The boys from the Black Zaporozhians 72nd Separate Mechanized Brigade send their regards to the invaders! And keenly watch them through the JAVELIN scopes. Glory to Ukraine!”

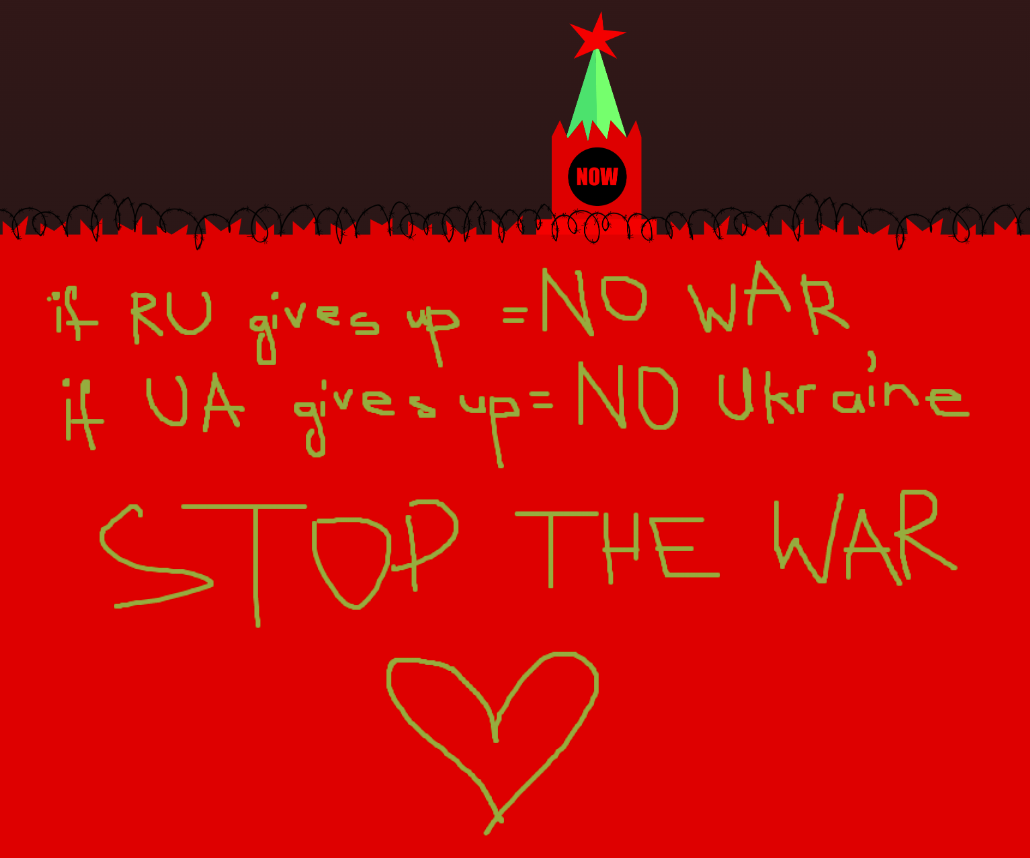

We are not just bricks in the wall

In their famous song, Pink Floyd say that any system is made of bricks and that we mustn’t become the material for its construction. It’s not only the Berlin Wall that became the symbol of authoritarian systems but also the Kremlin’s brick walls. Much like the Berlin Wall, though, the bricks of Moscow can become a canvas for expressing one’s opposition and resistance to what Russia does. The authors of We Are Not Just Bricks in the Walls project let users draw graffiti and anti-war slogans on a virtual Kremlin wall for a donation that will go toward helping the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Project participants’ names are kept secret for their safety

— Our web developer and his girlfriend conceived the project while sheltering in their corridor during Russian shelling. The gist of it is that anyone can draw anything on the Kremlin wall for a donation, leaving a virtual message from Ukraine to the entire world.

It took about a week to implement the project. We spent some UAH 150 on a domain and $50 on a server. Our team included four people: developer Yaroslav, designer/illustrator Artem, and project managers Nastia and Dania.

The idea is that there shouldn’t be any imperialist regimes in a civilized world. Our project aims to draw attention to the Russian regime and the Russo-Ukrainian war as a direct product of this regime.

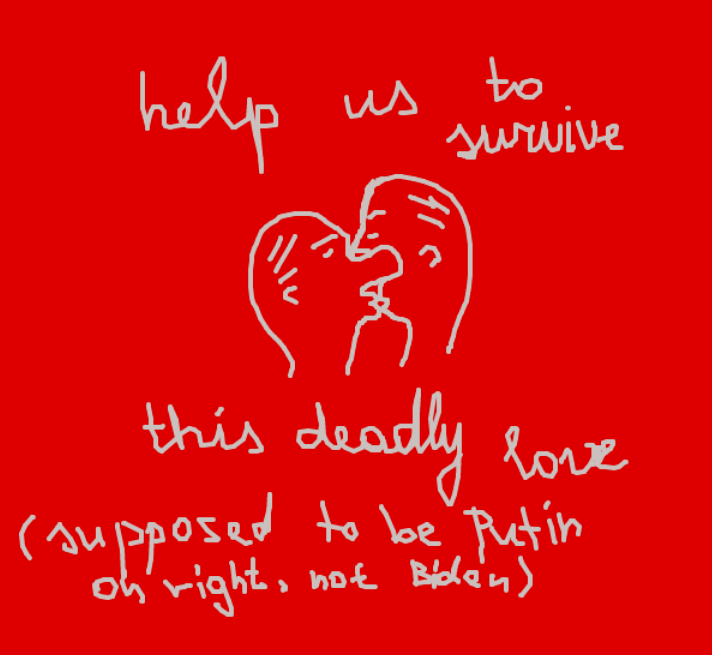

There are two slogans on our wall that we all like the most: “Opening your eyes is not a crime”, a message directly for the Russians, and the picture with the “Help us to survive this deadly love” slogan. Also, we decided to remove blatant hate speech.

So far, there are 30 writings on our wall, which is equivalent to $300, which were transferred directly to the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine. The project rose to popularity through word of mouth — people shared it on their Instagram Stories. Most donations came from our friends and friends of friends as well as from Europe and the USA.

Ukrainians say: ДЯКУЮ

The #ukrainianssaythankyou hashtag on Instagram shows posters with yellow-and-blue flags on the walls in Europe. The posters in 21 languages were designed by the authors of the Ukrainians say: THANK YOU project and can be freely downloaded and shared.

Designers/illustrators

— We wanted regular people from various countries to see our gratitude for their every donation, cup of tea, blanket, and banner at a rally. The project took about a week to launch. There are two of us in the team, but many more people have helped. Our only expense was to pay for a domain for our website.

Our goal was to make posters as easy to produce as possible. Therefore, we settled on black-and-white printing and yellow and blue office paper available at any stationery shop.

We regularly get messages from people who saw our posters in the street and scanned the QR codes in them. People from France, Germany, Poland, Estonia, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and many other countries send us their pictures. We are so happy that our project went global not only digitally. Just fancy that — someone who gave shelter to Ukrainians sees a physical poster with words of gratitude on their way to work!

New and best