Cell project: 9 drawings about life in prison

In 2020, a Ukrainian artist was arrested under article 260 of the Criminal Code of Georgia: “Illegal production, purchase, possession, transportation or distribution of drugs.” She was sentenced to four years in prison. But on April 9, 2022, the President of Georgia announced an amnesty for Ukrainian citizens, and Nastya was released. She is currently in Berlin and plans to return home soon.

While in prison, the artist painted a lot and worked on her “9 commandments of freedom” project. Bird in Flight publishes the drawings, followed by Nastia’s story about prison, art, and the war.

An artist.

— I grew up in a small city in the Dnipropetrovsk region. My whole life I’ve been surrounded by drugs. I watched drug addicts in my town, saw them preparing cheap dope. And I saw them hitting rock bottom.

It all looked creepy. So creepy that I haven’t had a single thought to try drugs. But then I moved to Kyiv. It was scary to find myself in a capital: big city, crazy energy, and I’m just standing there all alone. Yet, I knew that I had to take that step. Otherwise, I would’ve stayed in a small town that got stuck in 2003.

That was in Kyiv, where I saw drugs from another viewpoint. I dove headfirst into the whirl of youth life and its dazzling culture. Drugs looked different there. I imagined that they expanded my mind, gave me freedom, and showed the world from another perspective. I thought I found deeper meaning in life. But for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Drugs were pushing me towards the edge.

There was a lot of going on in Kyiv — some stories were personal, and others were even ground-breaking. At some point, I decided to change my life. I had a sudden urge to go to an unknown country and get lost there. And the Georgian mountains seemed to be a perfect place for a brand-new start.

I’ll say it as it is. I was selling drugs in Georgia. It all started when I was living in a drug dealer’s apartment. I helped him on some occasions. Then the pandemic began and the borders got closed. I couldn’t go back home. And one thing after another, I started selling drugs on a regular basis.

I was an addict, I saw no limits. But in Georgia, you can’t stay unnoticed for a long time. We’ve been followed for a month. First, they built a criminal case, then they arrested us. The thing that I dreaded the most has happened. But apart from wild terror, I also felt strangely relieved: it was over, no more lying.

I was an addict, I saw no limits. But in Georgia, you can’t stay unnoticed for a long time.

After a long trial, I was placed in a general correctional facility. Each day started with an inspection. At nine o’clock in the morning, the cells would open and every prisoner would be called out by their last name. We had an unchanging menu in the canteen — potatoes and pasta. From time to time we had a national Georgian beans meal called lobio. Prison guards behaved professionally and respected our personal space. There was only one male prison guard named Bacho. We could always tell when it was his shift — one of the prisoners used to dress up and comb her hair with extra care. Each day ended the same as it started — we got inspected and locked up in our cells.

We were allowed to decorate the cells. For example, my friend Elena, nicknamed I’m-begging-you, painted her cell pink and put pink curtains with Barbie on the bars. Women from Azerbaijan had their own style — their cells were all red, polka-dotted, with beads and rhinestones. My cell was cosmic. I made a moon and stars out of broken CDs and decorated the bars with silver confetti. At sunset, my cell lit up with sparkling rainbows.

Eyes always speak more, do not believe anyone in words and by appearance.

While you’re in prison, it’s like you’re being interrogated all the time, filmed on camera all the time, and watched by prison guards all the time. You’re in the spotlight.

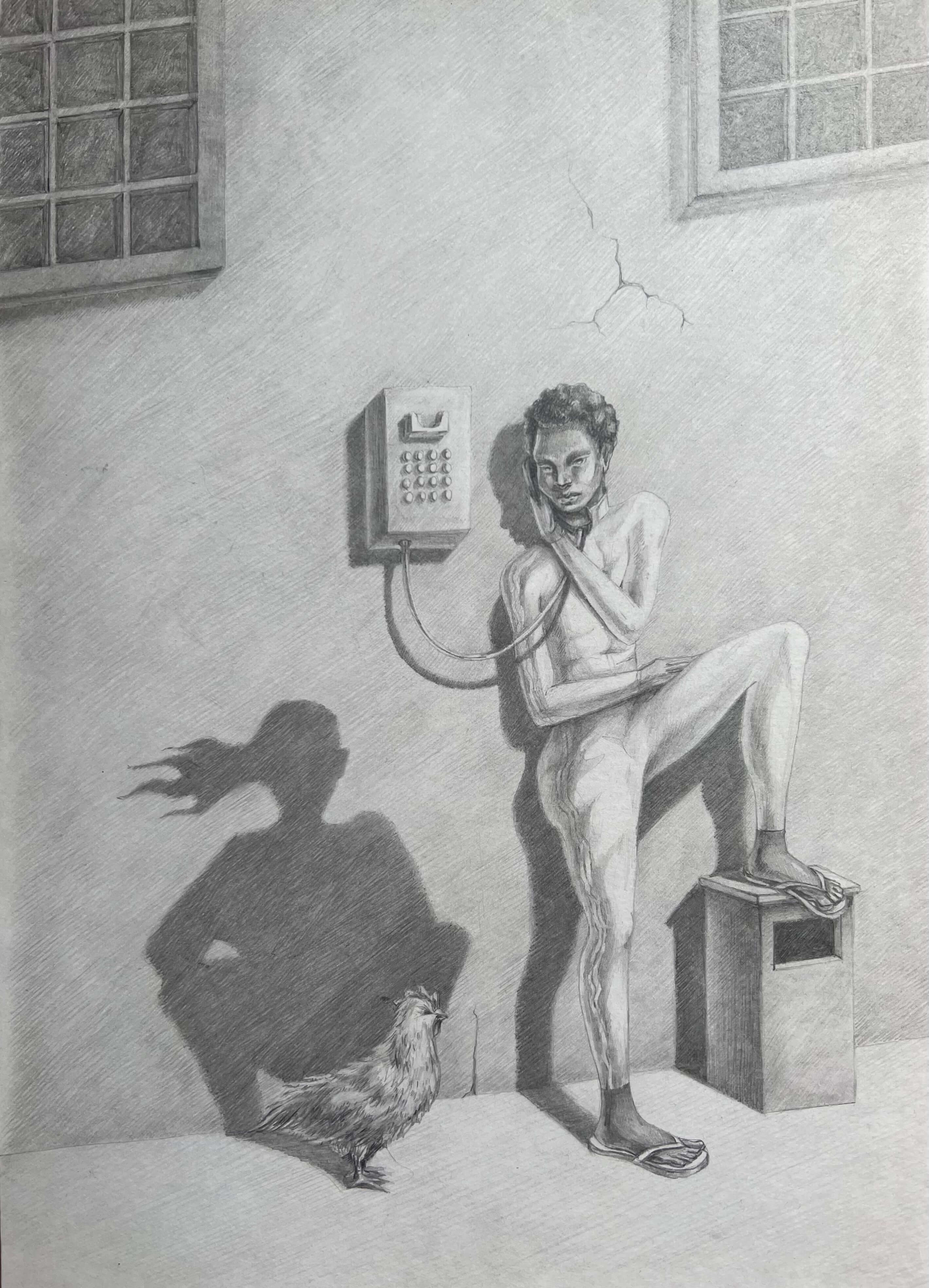

Give way to the nervous ones.

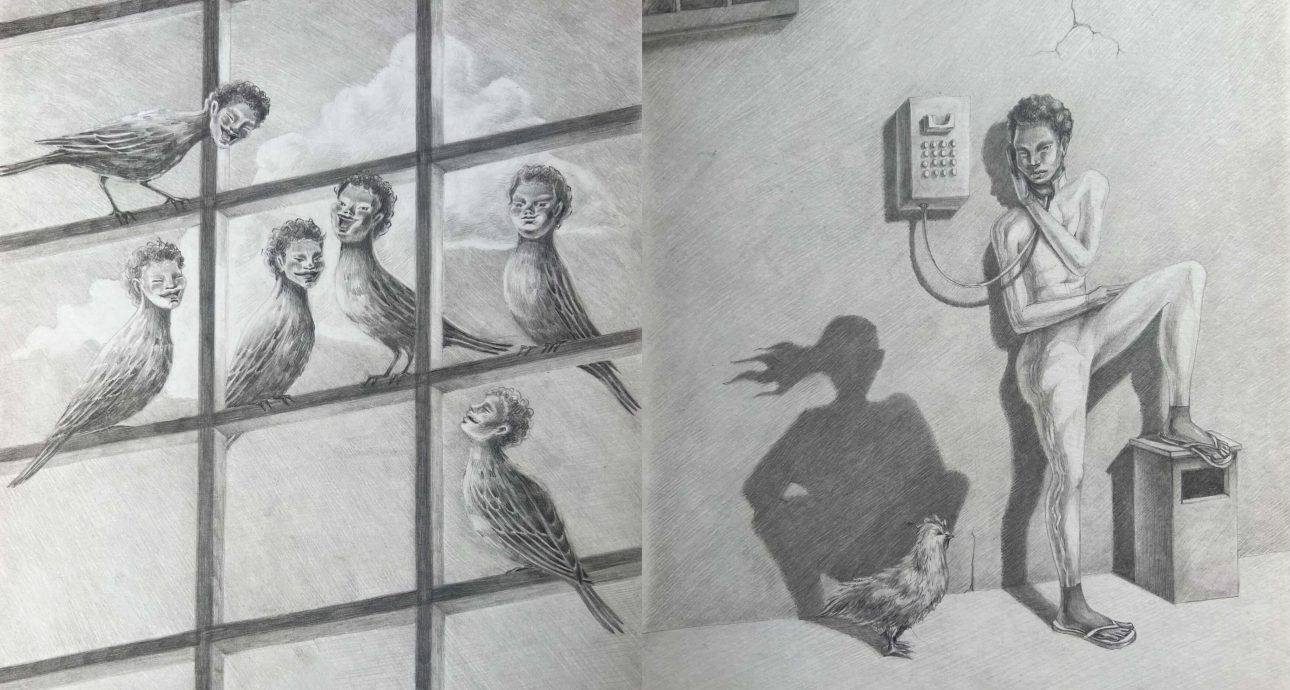

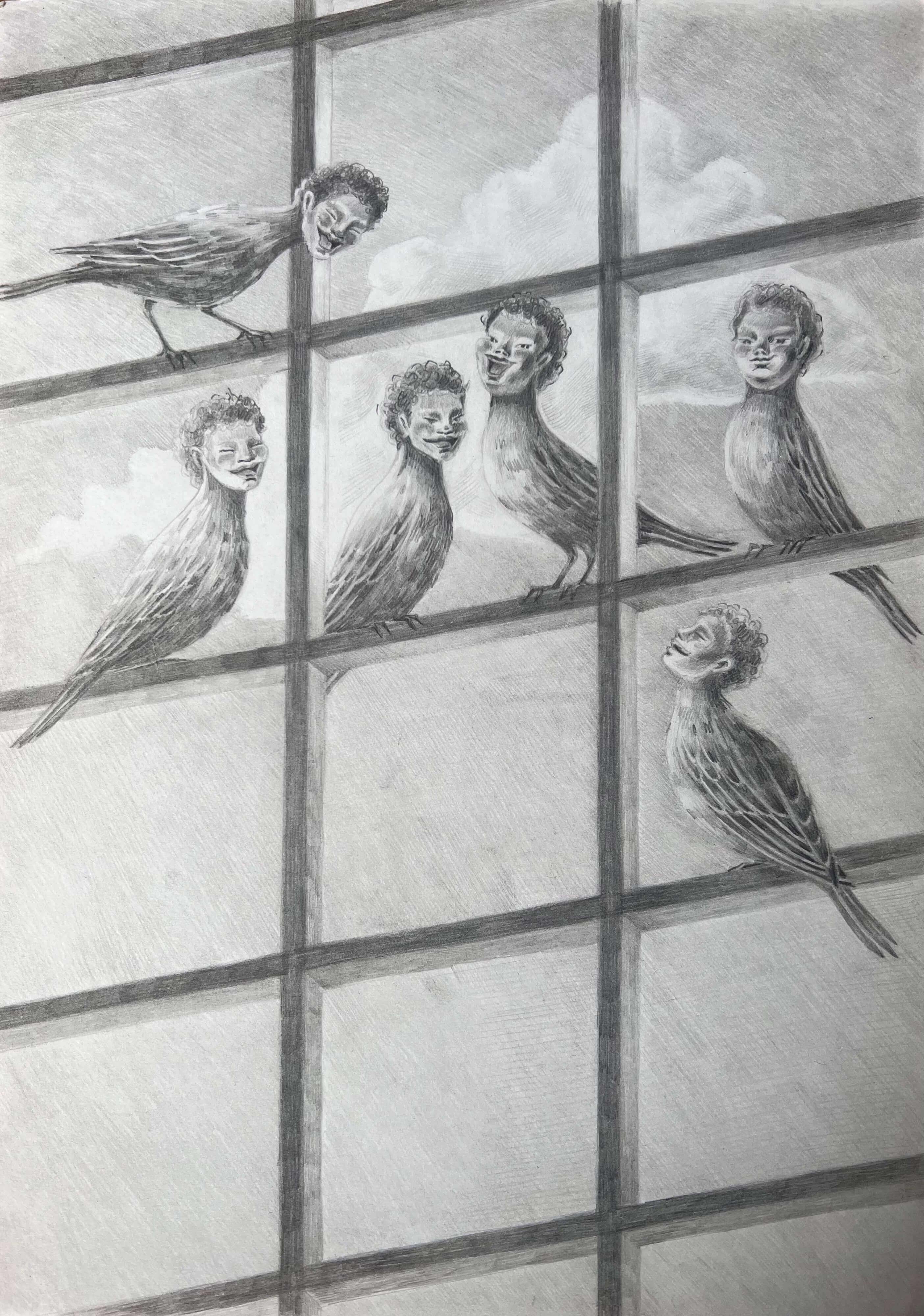

Birds' faces are people’s faces, who judge you every single day. Everywhere you look, the expression remains the same.

Do not communicate with anyone, do not get involved, do not subscribe to anything.

The chicken in the picture is real, its name is Tasiko. The girl is real too. That’s what phones in prison look like.

In 2014, there was a riot here, during which prisoners squatted in protest. Guards beat them on their legs. Since then, prisoners are not allowed to squat. That's why Tasiko’s shadow looks like this.

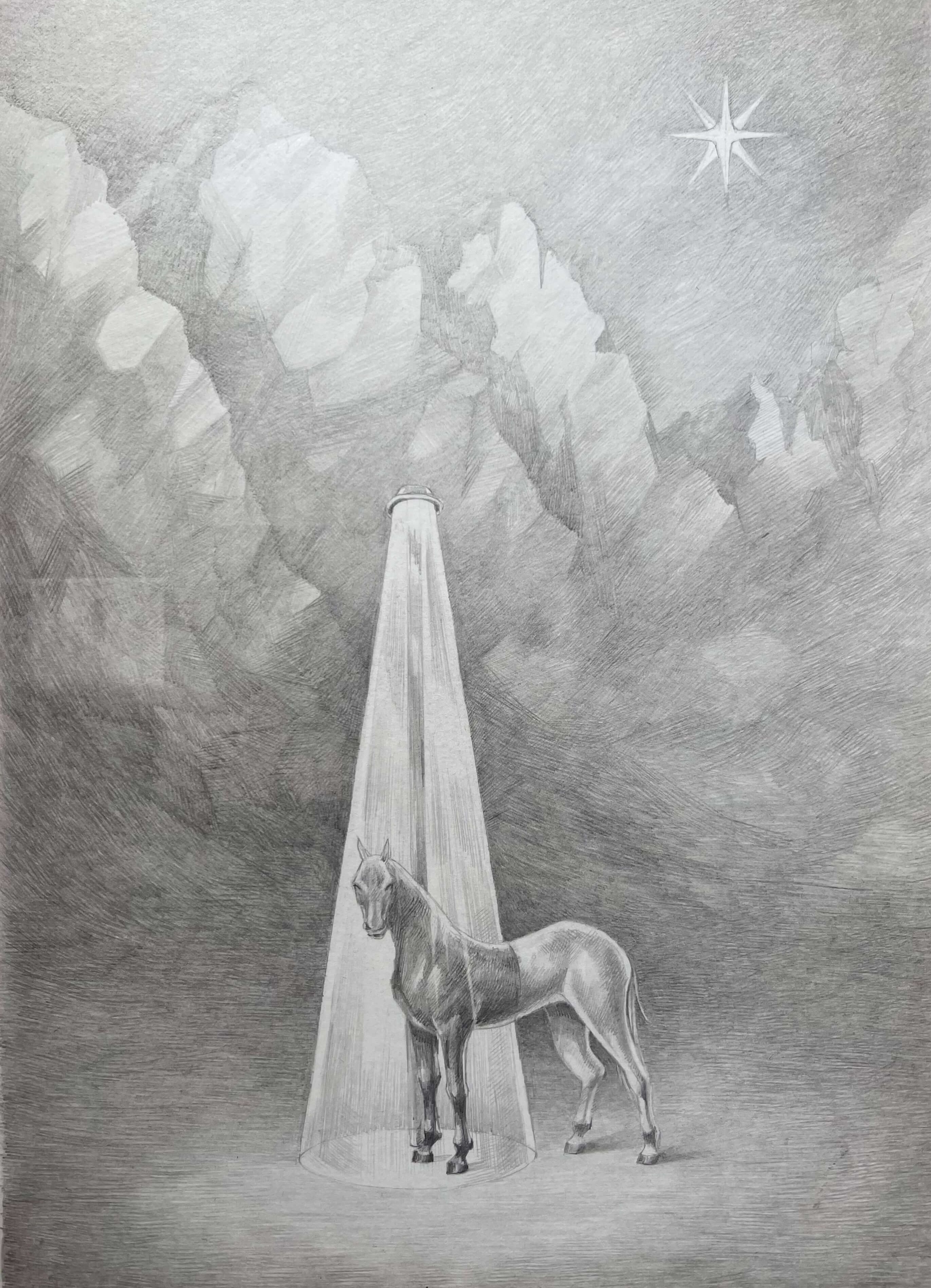

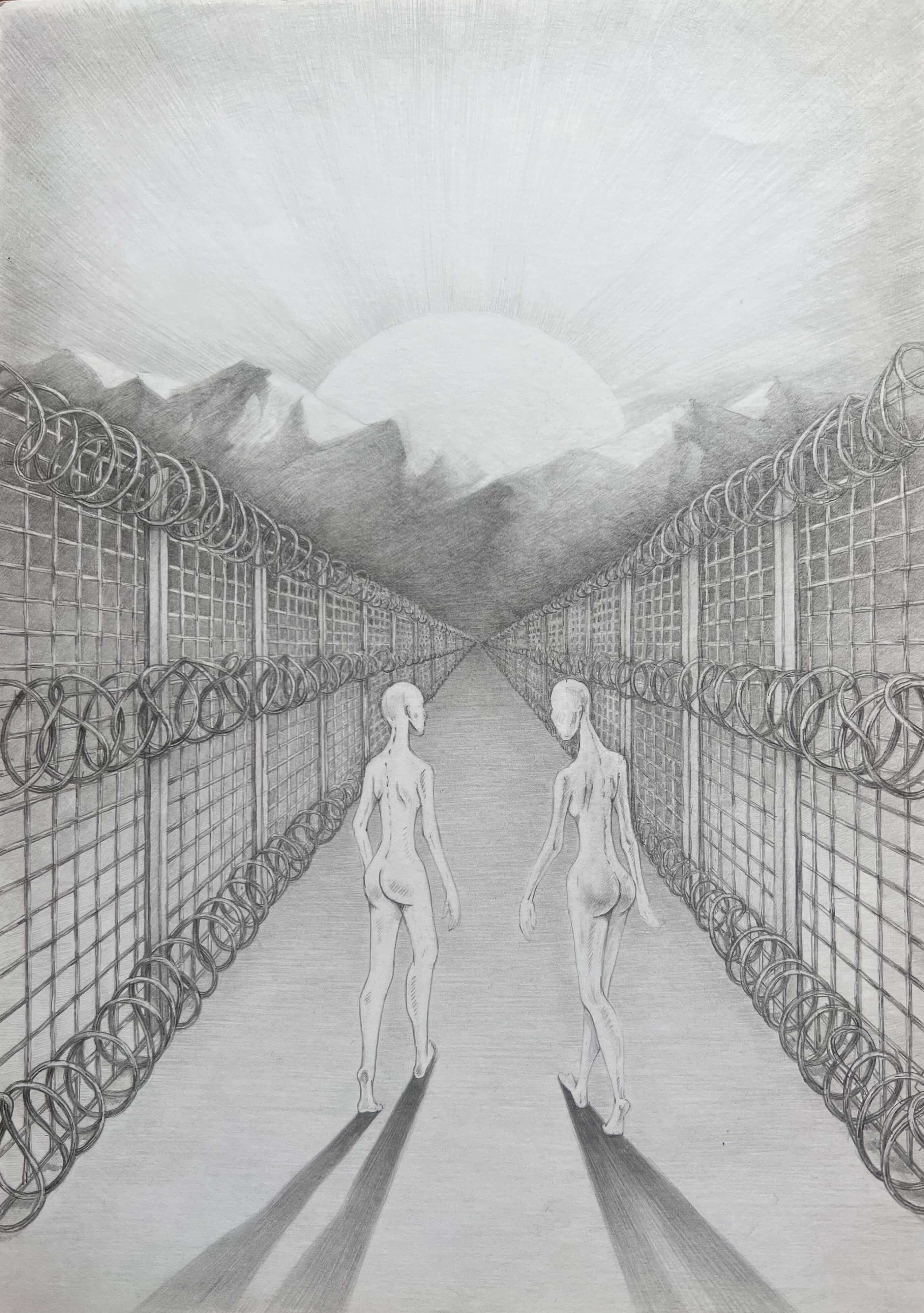

Do not get stuck on anything.

That’s what our walking route looked like. But in the reality, there was no way out. We only dreamt about it.

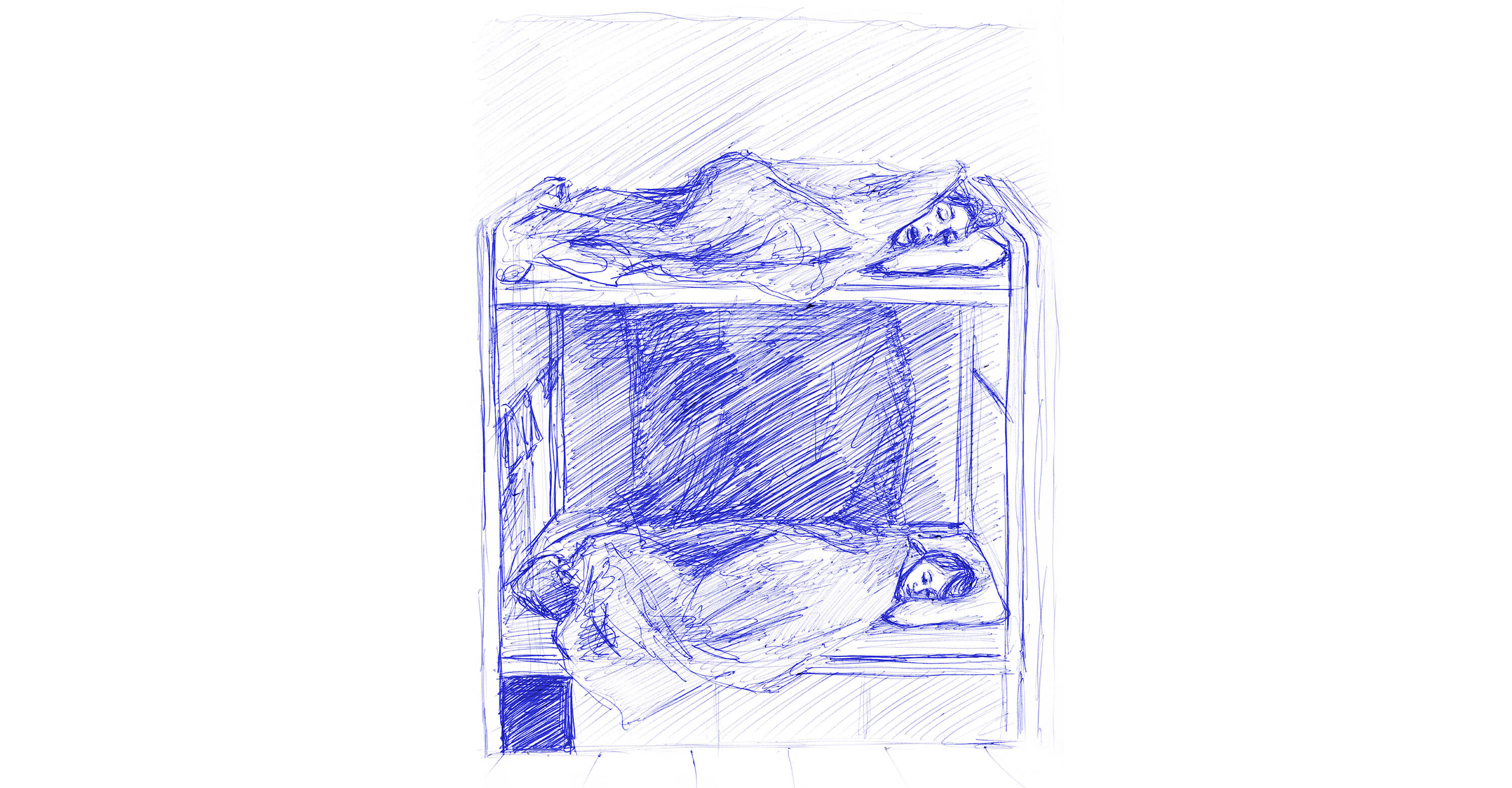

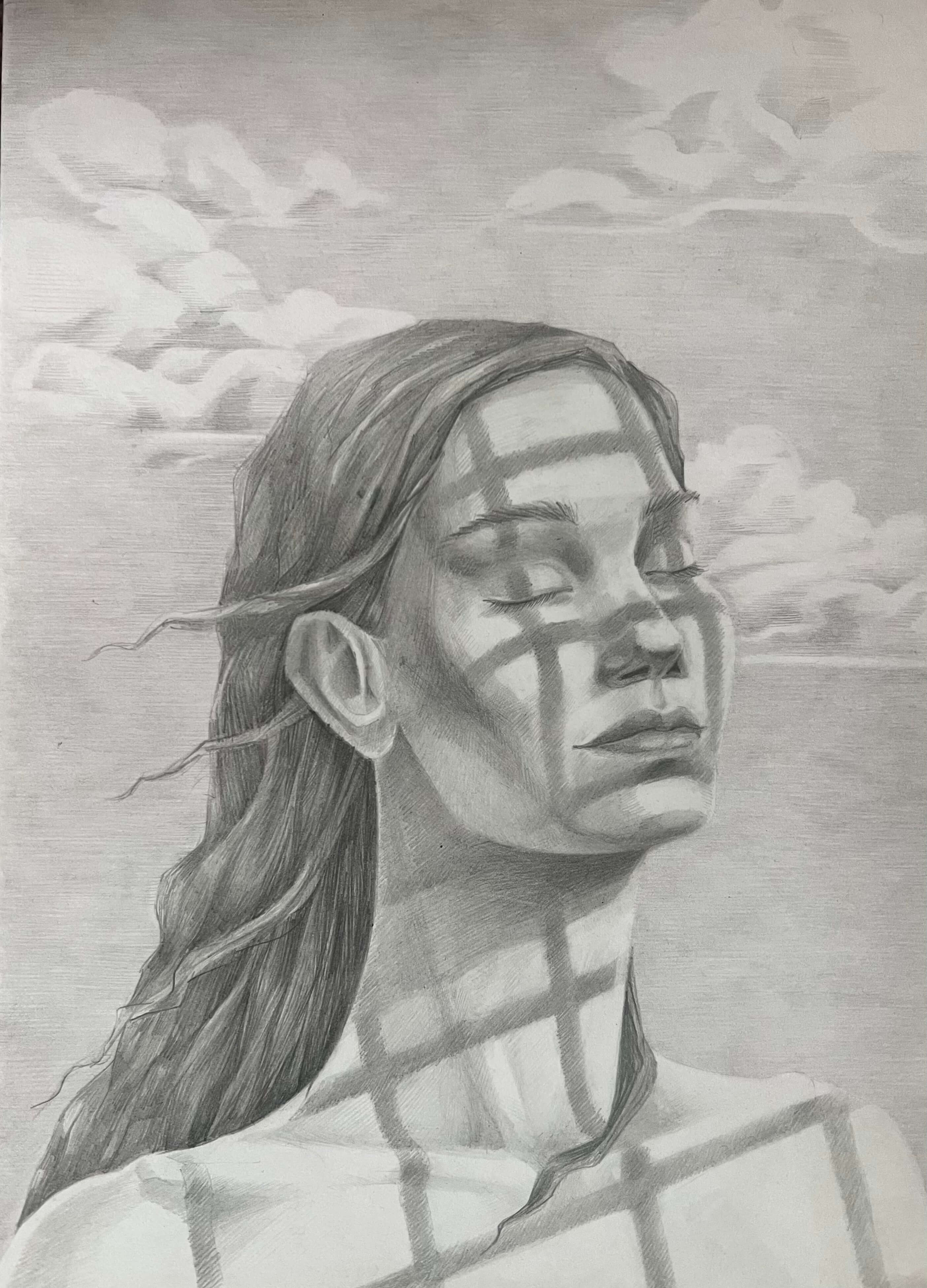

Follow the schedule, go to bed on time.

That’s how you feel when you dream about freedom. I saw many girls lost in thought, who didn’t even notice the shadow of the bars on their faces.

All days looked alike, but at the same time, different things kept happening. Sometimes I took part in concerts, sometimes we organized a theater performance to congratulate the warden. There was one time when we sang the Ukrainian national song “In a cherry orchard” with other Ukrainian girls, who served their sentences. But after all, it was just a single, never-ending groundhog day.

I didn’t talk to anybody during the first months. Then I met some girls, whom I could trust. We formed somewhat of a gang — young and thoughtful. But I never got involved with other prisoners, didn’t go to their cameras, which was a typical tradition there. I kept aside and tried not to become a part of prison life.

Every day I looked for something to keep myself occupied. My sentence was like a gift of free time. So I did sports, learned to play chess, and read a lot. And, of course, I drew.

The drawing was my escape, my rescue, and my way. I’ve spent two years in one place. But when I drew, I knew I was paving my way. My love for art has always saved me. When I was a young kid, I used to draw princesses in poofy dresses. But at some point, the dresses no longer fitted the format, the princesses showed their temper, and the landscapes changed to dark and wintery. The drawing is my golden ticket.

The drawing was my escape, my rescue, and my way.

When I was in prison, I drew what I saw. For example, there are many birds in my pictures. It seems to me that prisons and hospitals always attract a lot of birds. I think it’s some kind of compensation: the more people are imprisoned in their cells or wrecked bodies, the more sparrows and swallows fly freely around.

That whole time I felt an overwhelming yearning for home, for my family, for the streets of Kyiv. I craved an opportunity to simply go outside and walk around. Things like this — health, family, homeland, freedom — are usually taken for granted. The prison taught me how important they actually are.

When the war started, I knew about it straight off. It was the morning of February 24th, a day before my birthday. The girls helped me to bake a birthday cake. One of them, Natalie from Odesa, brought the news. She got off the phone call with her relatives and stormed into the cell crying and whimpering. She said that they are bombing us, attacking us with missiles, and that she is worried sick for her family. I rushed to the phone and called my sister and friends. They said: “We’re packing”, and these words made the war real to me. At first, it was unbearable, painful grief, which sometimes turned into anger. The following months were hell. It was the worst period of my imprisonment.

Every morning I went to a Georgian woman, who spoke Ukrainian and translated the news for me. I was devastated by the things I saw. Before that, I had my way, but now it was buried under ruins and death. I wanted to be at home, badly. I wanted to live this through with my family. If I had a chance to choose between war and prison, I’d choose the war. If I was to die, I wanted to die free and in my homeland.

I’d like to transform these feelings into art. But to draw something, one has to live through it. Now I’m finally free and return to Ukraine. I’ll visit my grandmother first, and then — back to Kyiv. I want to feel what my country has felt. I can’t even imagine how everything’s changed at home. It’s hard to make plans now, but I know for sure that I want to be an artist — both in life and on canvases.

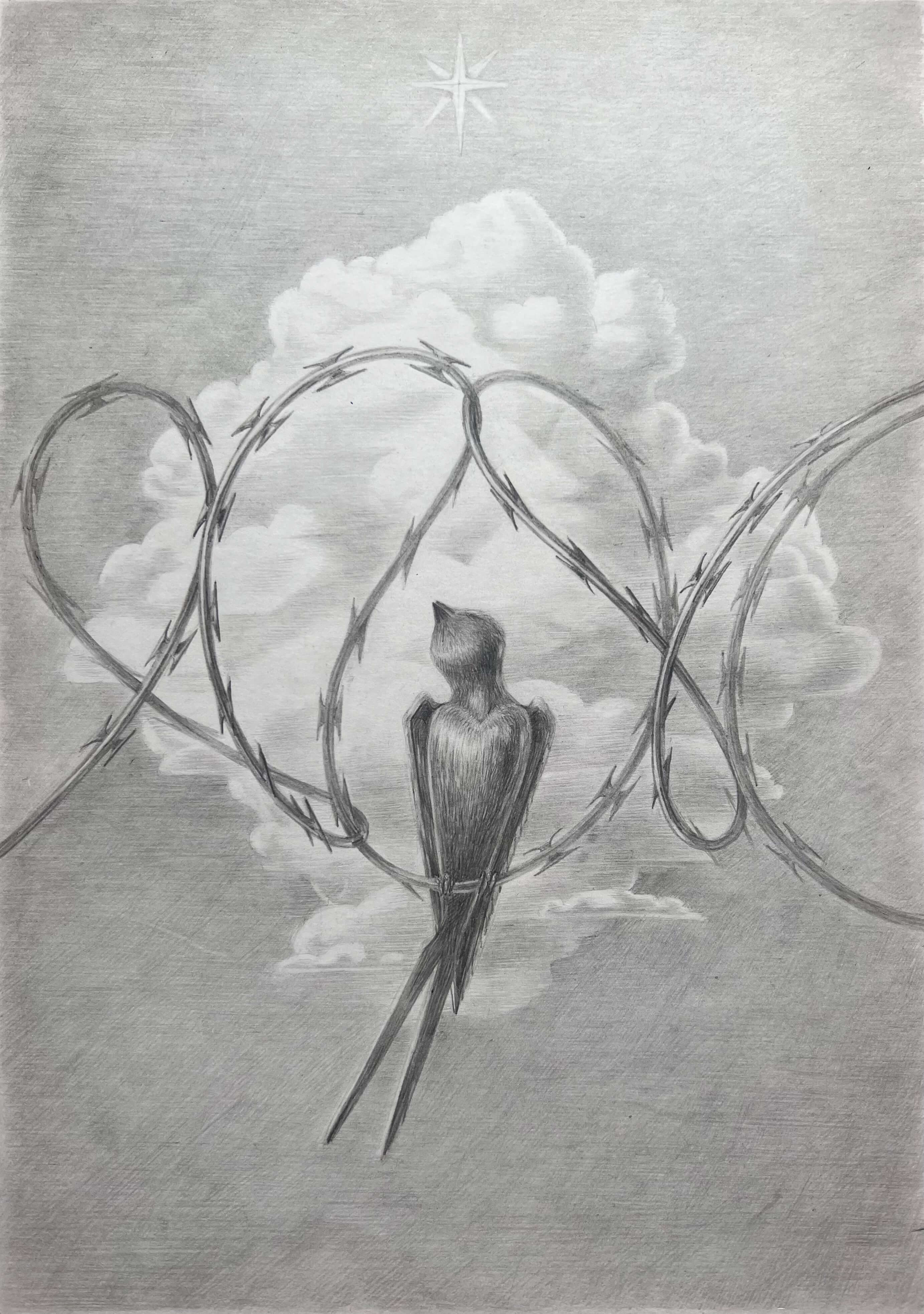

Believe.

Faith and superstition are closely connected in prison. A swallow means freedom, and, how ironic, those exact birds lived in prison.

No place for pity.

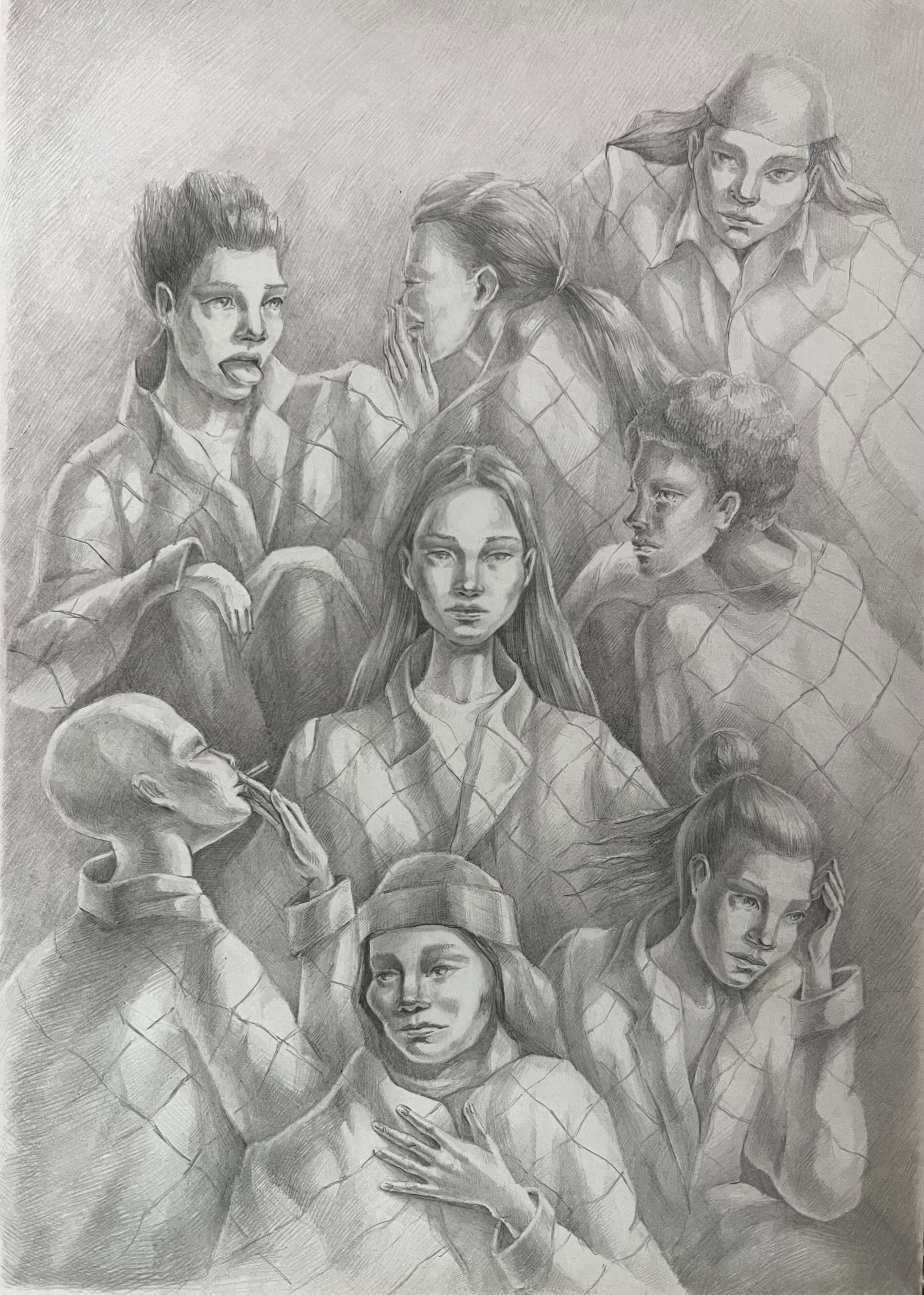

We are all different, we are all locked in one place, and we all think about the same thing. That’s what bonded us together.

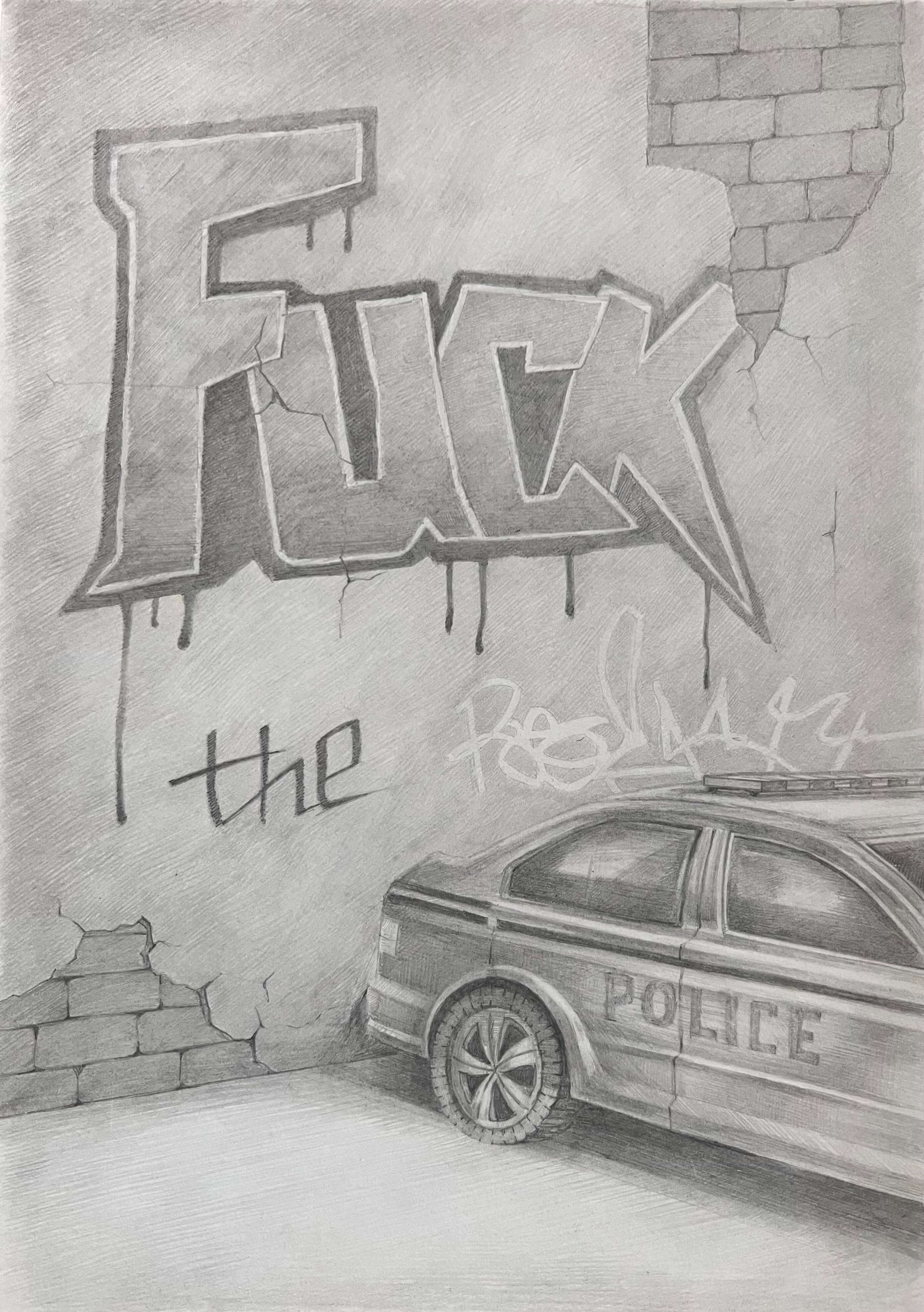

What happens in a trip, stays in a trip.

There are two prison subcultures: villains and cops, or black and red. My prison was painted red. There was no way to express my thoughts.

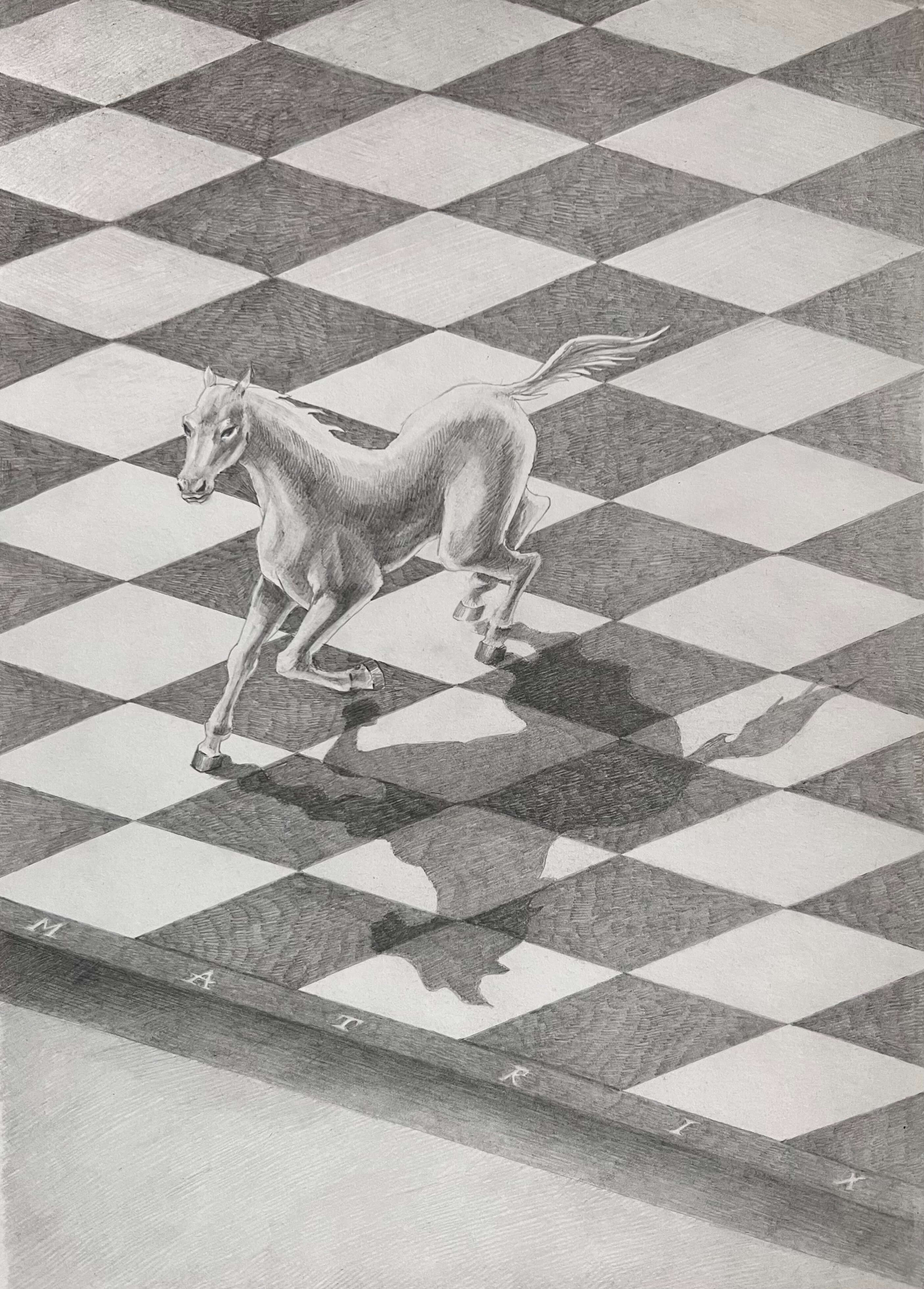

Remember who you are.

This is a story about exiting the system. The knight comes to life and quits the game.

New and best