In Search of a Person: The Portfolio of Ciprian Hord

A Romanian documentary photographer and clinical psychologist.

— It’s been 20 years since I graduated with a BA in Psychology, just 5 years ago I started working full-time as a clinical psychologist in a psychiatric hospital. Prior to this job, I worked exclusively in the field of visual journalism, either in television or as an independent documentary photographer.I don’t think I had the necessary maturity until now to cope with the profession of being a psychologist in a psychiatric hospital, a highly demanding place, both intellectually and emotionally.

I believe the most challenging aspect of this profession is not losing faith in the possibility of helping those patients who suffer from severe and difficultto-recover mental illnesses. There is also the danger of developing chronic fatigue and weariness, which can gradually lead to the development of cynicism and a lack of trust in humanism and compassion as general principles of behavior.

The most challenging aspect of this profession is not losing faith in the possibility of helping patients.

Working full-time in the hospital, I haven’t had enough time to dedicate to photography, despite my deep love for it. I started feeling the painful absence of photography, and as a result, I began taking photos of those I come into daily contact with – my patients. Gradually, I realized that these mini photoshoots with those who agreed to pose for me helped strengthen the therapeutic relationship between us and, consequently, brought some small benefits to their overall wellbeing.

Many psychiatric patients struggle with issues of identity, low self-esteem, or with memory deficits in the case of conditions such as dementia. And photography has the power to provide support in these areas. I always provide printed photos to those who pose for me and these generate a series of discussions, reflections, and positive emotions. I have received openness and support from the hospital administration, who understood the therapeutic nature of this project.

At the same time, through sharing these portraits, I aim to try and change the general perception of psychiatric conditions, which, at least in Romania, still carry a heavy stigma on the shoulders of patients. Visual documentation of hospitals and psychiatric patients is not a novelty, but the vast majority of photographers in the past focused either on the spectacular manifestations of illness or the inhumane conditions in some of these places. I try to concentrate on what unites us as human beings, not on what sets us apart.

Through sharing these portraits, I aim to try and change the general perception of psychiatric conditions.

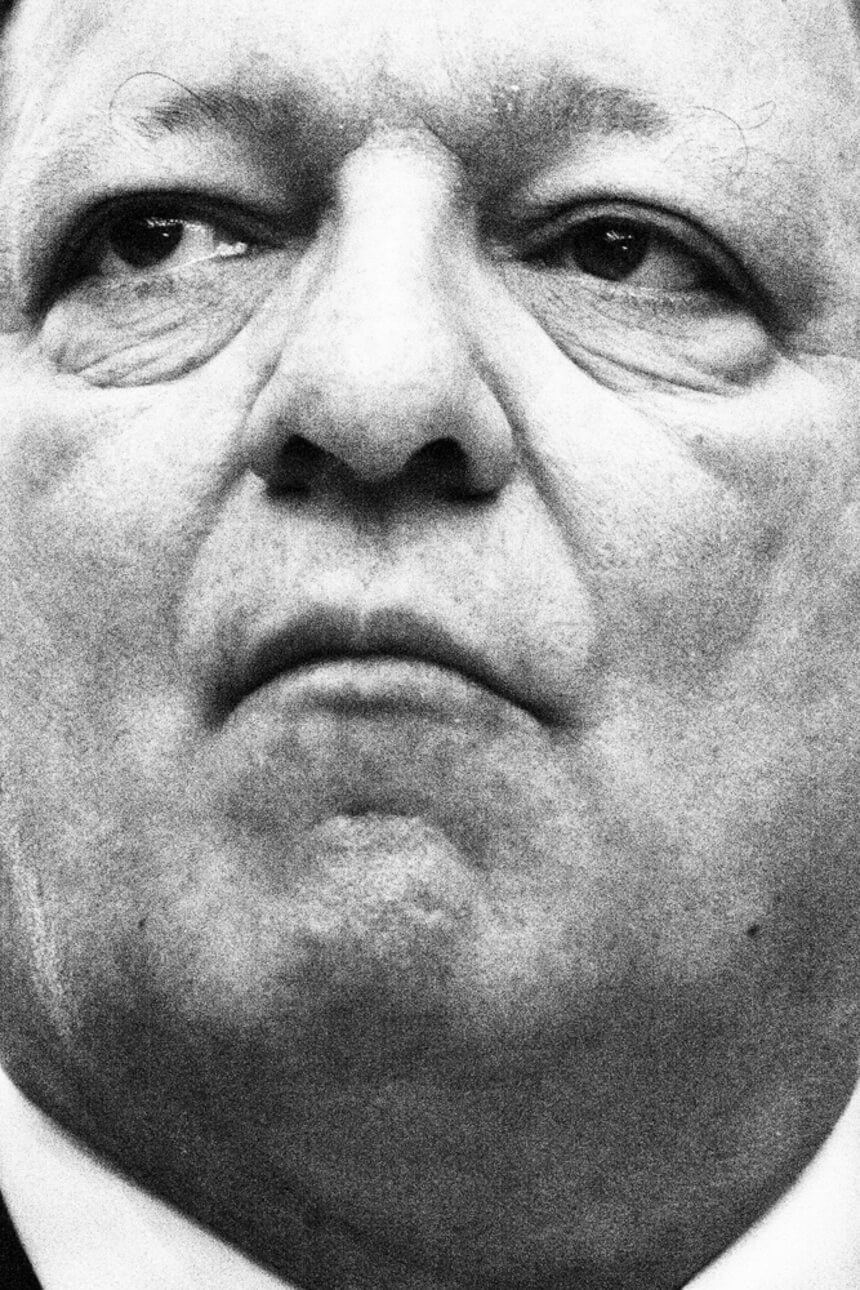

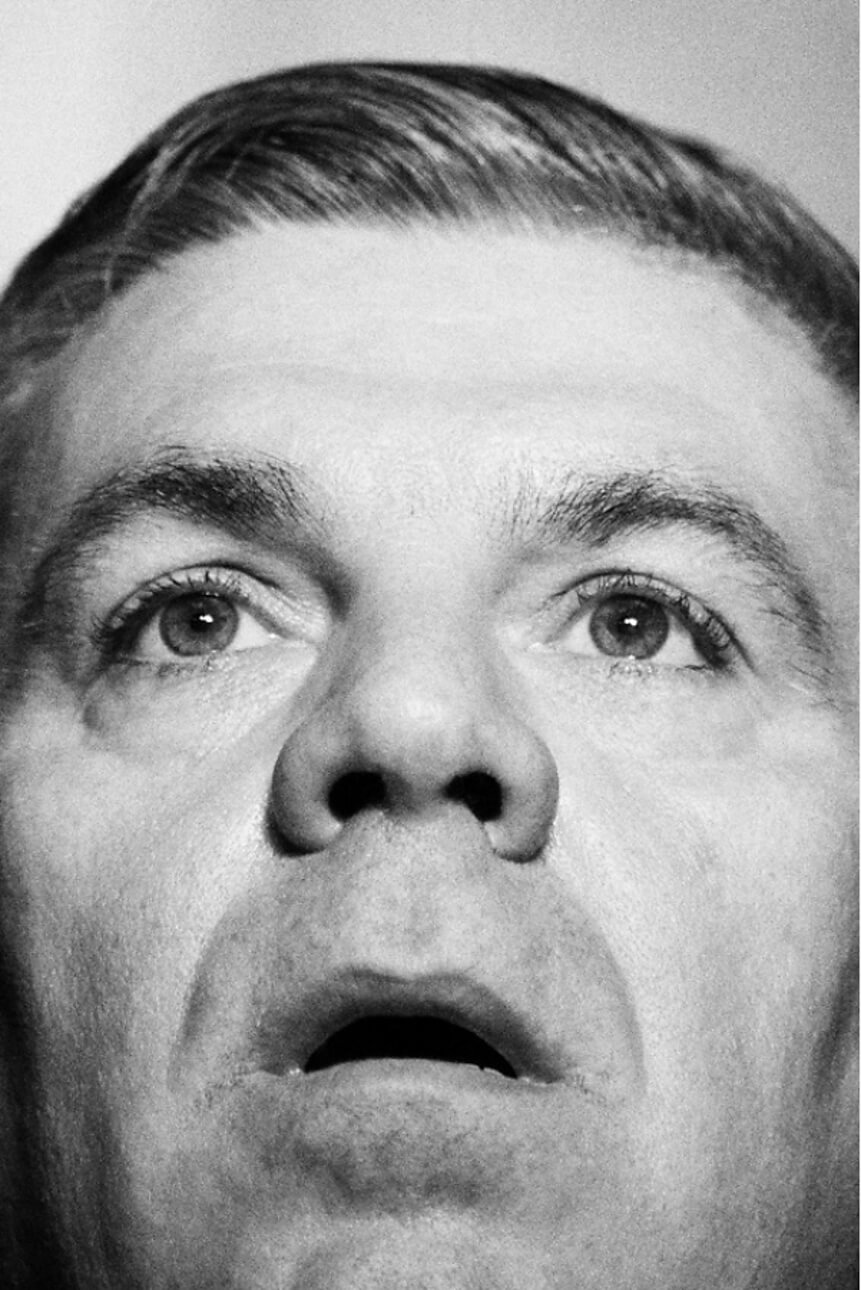

In addition to psychiatric patients, I also photographed politicians. I can’t say that my series on politicians is very original; it falls into an area that has been previously explored by renowned photographers and in some of the images I unintentionally copied the style adopted by them. Although they were perceived by the Romanian public as a satire of politicians, who are equated with corruption, I admit that my intention was somewhat different. I simply intended to conduct a character study, as I am fascinated by individuals whose main motivation is the pursuit of power. Honestly, I don’t dislike politicians at all. In an ideal society, a politician is in

the service of the citizens. However, in the Balkans, there is a long tradition of corruption, and politicians are an integrated part of this system. But I am much more afraid of a fanatical politician than a corrupt one. Unfortunately, fanaticism is experiencing a resurgence throughout Europe.

I was 9 years old in 1989, when the regime fell in Romania with bloodshed. I have a somewhat ambivalent relationship with that period. On one hand, I love that time because it was the most beautiful period of my life. Despite the material hardships, I was happy, like many other children. On the other hand, I become extremely inflamed when I notice even the slightest sympathies for communism today, even within some intellectual circles in Europe. This is because I realize that only someone who has not experienced such a regime firsthand, can imagine that a communist order can truly function without a serious infringement on individual freedom.

I become extremely inflamed when I notice even the slightest sympathies for communism today, even within some intellectual circles in Europe.

My father had a rebellious and entrepreneurial spirit, which was rare during those times. And I deeply regret that he passed away a few months before the fall of the communist regime, which he tried to deceive throughout his life.

Nicolae Steinhardt, an Orthodox monk and Romanian writer, was quoted by me in connection with monastic life, which I have had the opportunity to visually explore over time. He said that the stumbling block for a monk is not uninterrupted prayer, exhausting work, or very long fasts, but the temptation to get angry with one’s fellow monk due to their small malice and annoying habits.

I am searching for The Human, as Diogenes once said. Perhaps this humanistic attitude is considered outdated today, but I am genuinely interested in the essence of human nature, those aspects that often help us transcend material reality and the cruelty of nature. I am interested in kindness, freedom, the joy of living, and love. And I find them everywhere.

Now I am working on a doctoral degree in visual arts, and I’m seeking solutions to allocate more and more time to photography.

New and best