“If You Keep Silent, the World Will Hear the Rapist’s Lies:” Former Inmate of Serbian Concentration Camp on Courts After War

1907 was the year when sexual assault in wartime was acknowledged to be a war crime. This step hardly changed anything. Rape cases were never tried either in Nuremberg or during any other trial after World War II.

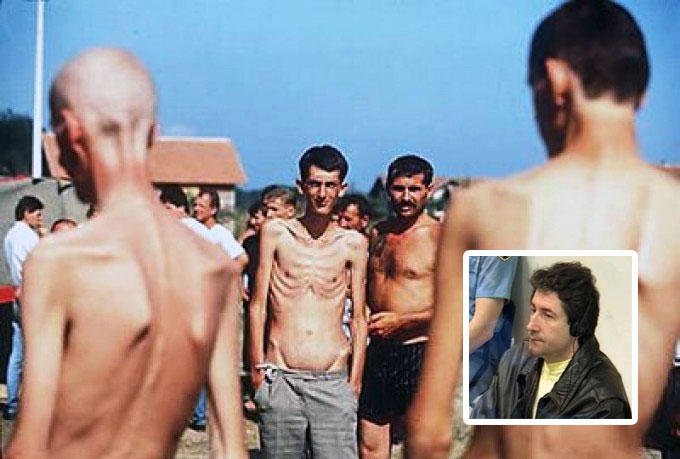

It was not until 1993 that the situation changed. Then, after the war in Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Tribunal passed sentences for sex crimes. Rape was declared to be a form of torture, and sexual slavery, a crime against humanity. One of those that made it happen was Bosnian activist Nusreta Sivac.

Sivac is 71 years old. Born in Prijedor, she studied law and worked as a judge. In 1992, she spent three months in Omarska, a Serbian concentration camp for Bosniaks. When she was out of the camp, she became an activist, gathering information on sex crimes perpetrated by Serbs, testifying in court, and encouraging other inmates to follow suit.

Nusreta Sivac told Bird in Flight what helped her survive the terrors of the camp and why it is important to speak of events one wishes to forget.

Before the war, you worked as a judge? Why did you choose this career?

Firstly, I was interested in court action and the judicial system. It is a fascinating area. On the one hand, you can be independent and autonomous, and on the other, you have to work within the law. Secondly, I didn’t want to work for a private business.

On the cusp of war, there are always those who know that there will be war and those who do not expect it. Were you ready when the war started?

I’d say I belong to neither group. The war was not unexpected because the situation was escalating gradually. Slovenia was the first to declare independence, but the warfare there was short-lived. Then it started in Croatia, and Prijedor, where I lived back then, is on the border. We were watching the mobilization and arms deliveries. Of course, many thought something similar might happen in Bosnia too.

At the same time, deep down in our hearts, we believed our country was so multicultural that the war here was practically impossible.

Now I realize that Serbia had it all planned out and ready. Guided by its sick political ideology, the country was investing a lot of money in the army, while the Bosnians turned out unprepared for the war.

How did you end up in the Omarska camp?

The Serbs had a plan. In most of the occupied cities, they would remove local authorities and mass media executives (those positions were only allowed to Serbs) and launch their propaganda.

At the end of April 1992, the Serb Democratic Party seized Prijedor. I was fired, and in June, they caught me and took me to the concentration camp in the town of Omarska, the cruelest and the largest camp in Bosnia.

There were around 3.5 thousand men there, although the figure was fluctuating: some were killed, others were brought in. They were mostly intellectuals. There were also those who had been imprisoned for providing information on Serbs. Women were much fewer—as few as 37. Five of them did not survive the camp. Their bodies were buried in mass graves.

To be honest, I didn’t grasp what was going on at first. Of course, I had heard of that camp: there had been talk about it in the city. It was mostly for men, so when I was taken, I decided it was a mistake and believed I would soon be let out. I was mistaken.

What kinds of women were there?

All kinds. And they lived in all kinds of conditions, too. For instance, one inmate lived in the “white house” — that is, the main torture chamber. That woman was considered a radical. There was also a Serb who was convicted of selling weapons to Muslims. She was not tortured as much as others and lived in better conditions. Overall, women were tortured less than men. Instead, we lived through especially cruel rape.

Women were tortured less than men, but instead, we lived through cruel rape.

What were you accused of?

Nothing. I was an apolitical citizen, not a member of any political party: my job prevented me from it. But it didn’t matter a jot. To end up in the camp, it was enough to be not a Serb. I am a Bosniak and a Muslim.

What constituted the camp?

It was set up in the territory of a former iron ore mine outside of town. The guards worked in three shifts.

What was your daily routine?

We started the day from counting the bodies of those tortured to death, which were piled up before the “white house” in the morning. We just counted them in our minds. The number of corpses apparently depended on the mood of supervisors. On some days, there were as many as twenty-five.

Twice a day we (the women) distributed food: rotten peas, cabbage, bread. And in the evening, we would go to the second floor, where tortures happened, and wash the floors of blood and hair and remove the torture instruments. When we were done, we would go to sleep — in the same rooms where camp employees tortured people.

Viktor Frankl wrote that it is through a search for meaning and purpose in life and not just waiting for liberation that people survived death camps. Do you agree with this?

Yes, absolutely.

What helped you survive and not break down?

There were a lot of people I knew in the camp: my family, friends, and acquaintances. When you get used to life in the camp, you stop believing you will ever be able to get out. The guards’ behavior added to depressive thoughts: they had long gotten tired of their work, so they were just waiting for an order to kill the inmates, bury their bodies, and go away. So I dreamt of surviving and telling the world about everything that was going on there.

I dreamt of surviving and telling the world about everything that was going on in the camp.

How did you get out?

I was let go thanks to The Guardian’s journalist Ed Vulliamy and the International Committee of the Red Cross. When

What was the first thing you did after you got out?

I went to my hometown. There I learned that my colleague, a Serb, was now living in my apartment. He thought I would never come back. So I decided to leave Prijedor at once. But the roads were closed, so I could only leave after several months. I settled down in Croatia.

the former President of Republika Srpska, who was sentenced to life in prison by the Tribunal

When was the first time that you were able to speak out about what had happened to you in the camp?

It took me some time. My brother and his family were in the concentration camp too, so I kept silent for their sake. When my kin got out, I started speaking officially and openly about everything that had been going on in the camp. I spoke to compatriot journalists and international organizations. Later on, a few months after I got out, I first spoke with a representative of the international tribunal.

I read that when you came back home, you saw the camp guards on the streets. How did it feel, living next to them?

It was hard.

I came back to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1996 but could not reach Prijedor: those who were exiled from the city were forbidden to return. It was only six years later that I managed to get in. International organizations helped me get my apartment back.

At first, I thought I made a mistake in coming back to Prijedor. The atmosphere in the city is still difficult now, not to mention in the early 2000s.

Why?

Because the criminals are walking around the city alive and well. They do not reveal the locations of mass graves, so 600 people are still considered missing. The locals live in some kind of an imaginary world. They have distanced themselves from the events of the war, and some, including the authorities, deny those crimes altogether.

Despite the fact that everyone is afraid to speak out, you were gathering evidence of the crimes, talking to women who either witnessed or survived rape during that war. How did you manage to persuade them to talk?

It was difficult and took a lot of time. While in exile, we created the Women’s Association of Bosnia and Herzegovina and started talking — together.

Our effort resulted in criminal proceedings against certain people. For the first time in history, sexual assault was recognized to be a war crime.

However, many women are still wary of talking about it, and I respect everyone’s opinion. The aftermath is harrowing, and every woman lives with it.

Wasn’t rape considered a war crime during World War II?

It was, but the issue was never addressed in Nuremberg, and no one was punished for sex crimes. The Hague court recognized it judicially and sentenced individuals. When the trials ended, the cases were transferred to the national jurisdiction.

The Hague court was the first ever to legally recognize rape as a war crime.

Despite a lot of testimonies and evidence, you were not able to attain a sentence for every perpetrator. Why?

Some crimes did not receive legal confirmation. Besides, the court only lasted for so long, so it only tried the gravest crimes. Other cases were transferred to national courts, which, unfortunately, turned out to be not so efficient: the proceedings are still ongoing. Because of this languidness, criminals do not live to hear their sentences.

Are you following the Russo-Ukrainian war?

I am, but not as closely as I did in the beginning: it is more difficult for me now. Moreover, in my part of the country, the presented facts are distorted. At any rate, I hope that the war in Ukraine ends before long because it’s a nightmare.

What advice would you give to Ukrainians that became victims of sexual assault perpetrated by Russian soldiers?

Talk about it, clearly and unambiguously. This will result in many criminal cases getting evaluated legally and solved. If you keep silent, the world will hear the aggressor’s lies.

My activism is a dangerous business, especially in the environment I live in. But fear is a terrible, blocking emotion. A lot of those who spoke out on Serbs’ crimes went missing. Because of that, people are afraid of talking. But there are those who speak out because they believe that the good always wins. It will win in Russia’s war against Ukraine too. Justice will prevail. So do not keep silent.

Photos of Nusreta Sivac: Dijana Muminovic for Bird in Flight

New and best