“I See Death as a Part of My Life”: An Interview with a Combat Medic

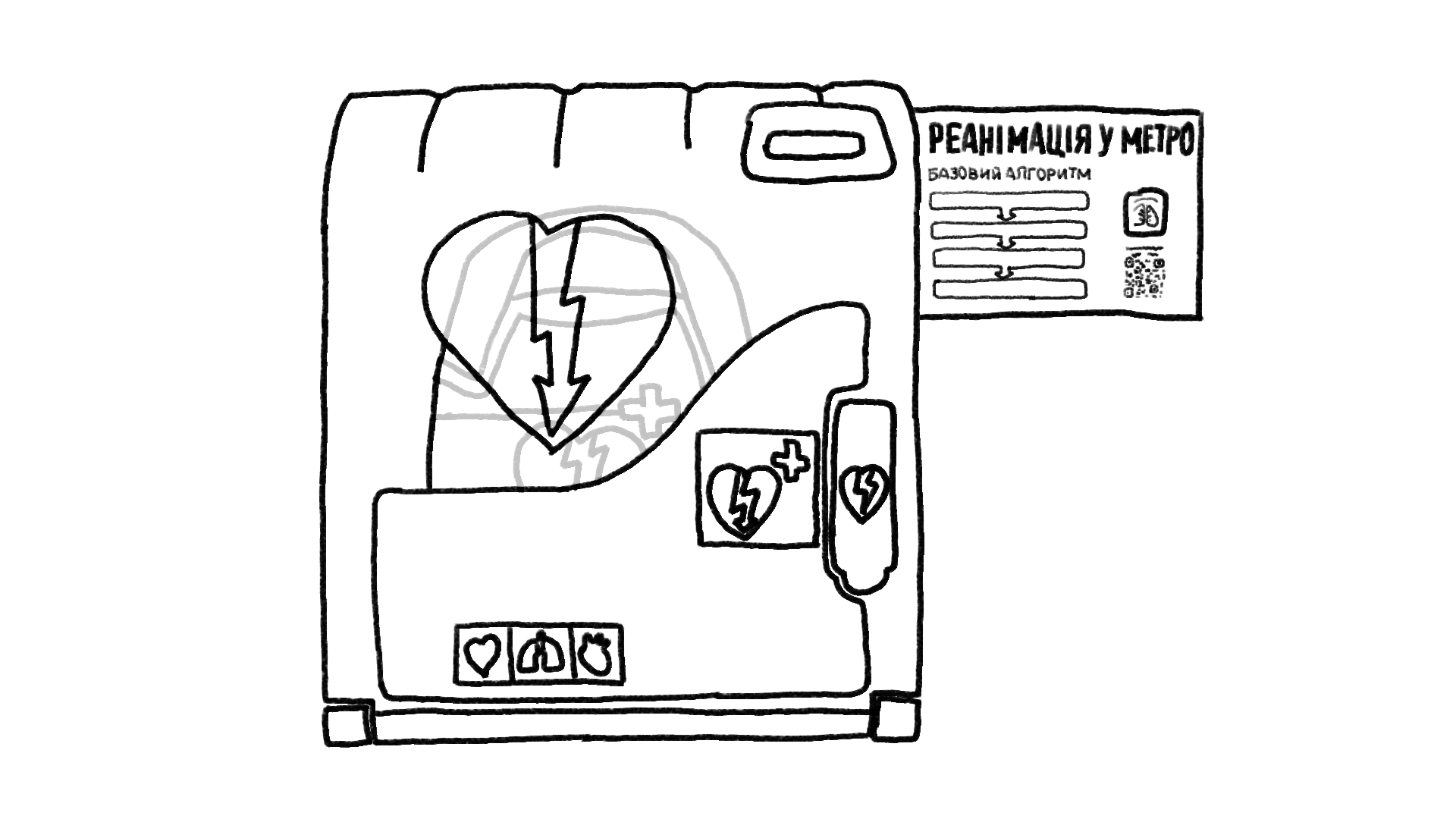

When Masha was 17 years old, she painted a red cross on her t-shirt and joined the medical service of Maydan. She joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine in 2014. Studied in Germany, received certification in combat medicine according to the US standards. Co-created a tactical medicine training program of the Ukrainian Armed Forces General Staff and taught more than 8, 000 military. In her civil life, Nazarova is an active volunteer. For example, thanks to her project “ReaniMetro” Kyiv metro stations are now equipped with defibrillators.

Masha tells Bird in Flight about the most common diseases on the front line, ultrasound in trenches, and about Pyrohov, who “stitched soldiers’ heads back on”.

Have you had a feeling that there is going to be a big war?

This whole hysteria about the “upcoming war” bugged me a bit, because, actually, that war has been here for 8 years. On February 24, I was in Washington, attending a governmental experience exchange program together with my colleagues. When the full-scale invasion started, I went straight back home.

What’s your main focus now — teaching or directly working with patients?

It’s teaching. There are a lot of new people and volunteers in the army. And the situation is as follows: even if each unit has a great combat medic, soldiers still need to know how to help themselves — otherwise their chances to survive are quite low. This is why I’m helping to teach new instructors. I want every combat medic not only to give professional medical assistance but also to be able to teach others do the same. I want every unit to have a training tourniquet and precise instructions, and I want combat medics to spend every free minute teaching their people.

Even if each unit has a great combat medic, soldiers still need to know how to help themselves — otherwise their chances to survive are quite low.

Depending on the effectiveness of this system, thousands of lives can be either saved or lost.

In an ideal world I would focus solely on teaching. In reality, I have to attend patients all the time. We often organize training near the front line, which means that any moment we might need to get off the ground and go evacuate the wounded personnel. Or in other cases, the wounded personnel are brought to our dislocation and we have to provide medical aid.

That’s how it was in Irpin a couple of months ago. We were training, when the shelling began. Four people were injured, one received critical injuries. His comrade did not lose his head and applied a tourniquet correctly — we just learned that part. Basically, he saved the other person’s life. When the wounded soldier was brought to us, we proceeded with giving him profound medical aid.

And how does this system work, exactly? Can a serviceman be on a battlefield and not know how to apply a tourniquet?

Well, of course, no one on a draft board asks people to pass a test on applying tourniquets. This is excluding a few super-elite units. But in general, the point of the army is that anyone can join in, even with no experience whatsoever. This is why every unit has to be trained, and you need to ask your local commanders if their people have been trained in tactical medicine.

February and March were difficult. We had cases, when freshly recruited people were sent to the second front line to dig trenches and got under shelling. But back in the day, the front line was almost everywhere. Now it’s almost impossible to imagine a situation when you join the army today and find yourself on the front line tomorrow, And a reasonable commander can always take care of the unit’s training. Sometimes, commanders can call instructors even to the first line of defense. When we are there, our training can be interrupted by a hit at any moment, but we still go there and do our best.

What are the most common injuries?

It’s a standard statistics of mine and explosive injuries: legs and groin are injured more frequently than the upper body. But this is my personal observation. We could have collected a lot of valuable research data for tactical medicine here, in Ukraine, but unfortunately, we do not accumulate data now, we don’t have precise statistics.

But we plan to purchase GoPro cameras for combat medics. This way, they will be able to record their work, and we will have a chance to use their materials for future research and learning. We used to analyze different situations recorded by the American combat medics. But we do have a lot of our own material to work on. It has just never been systematically collected. It’s time to fix it.

We could have collected a lot of valuable research data for tactical medicine here, in Ukraine.

What has changed in tactical medicine in these past years?

To start with, medical equipment has changed. Some things became more affordable, other things became more mobile. For instance, there are now great portative ultrasound devices. With their help, medics can conduct ultrasound diagnostics not only in a car, but even in trenches. All it takes is to connect a device to your phone and that’s it. Medical aid protocols are constantly updated, but there is one important detail. The science of tactical medicine takes place in the USA, mainly. They use their experience from Afghanistan and Iraq as a grounding basis. Currently, the US doesn’t have a lot of military operations, but they have loads of amazing medical equipment instead. That is why the training course is rather limited.

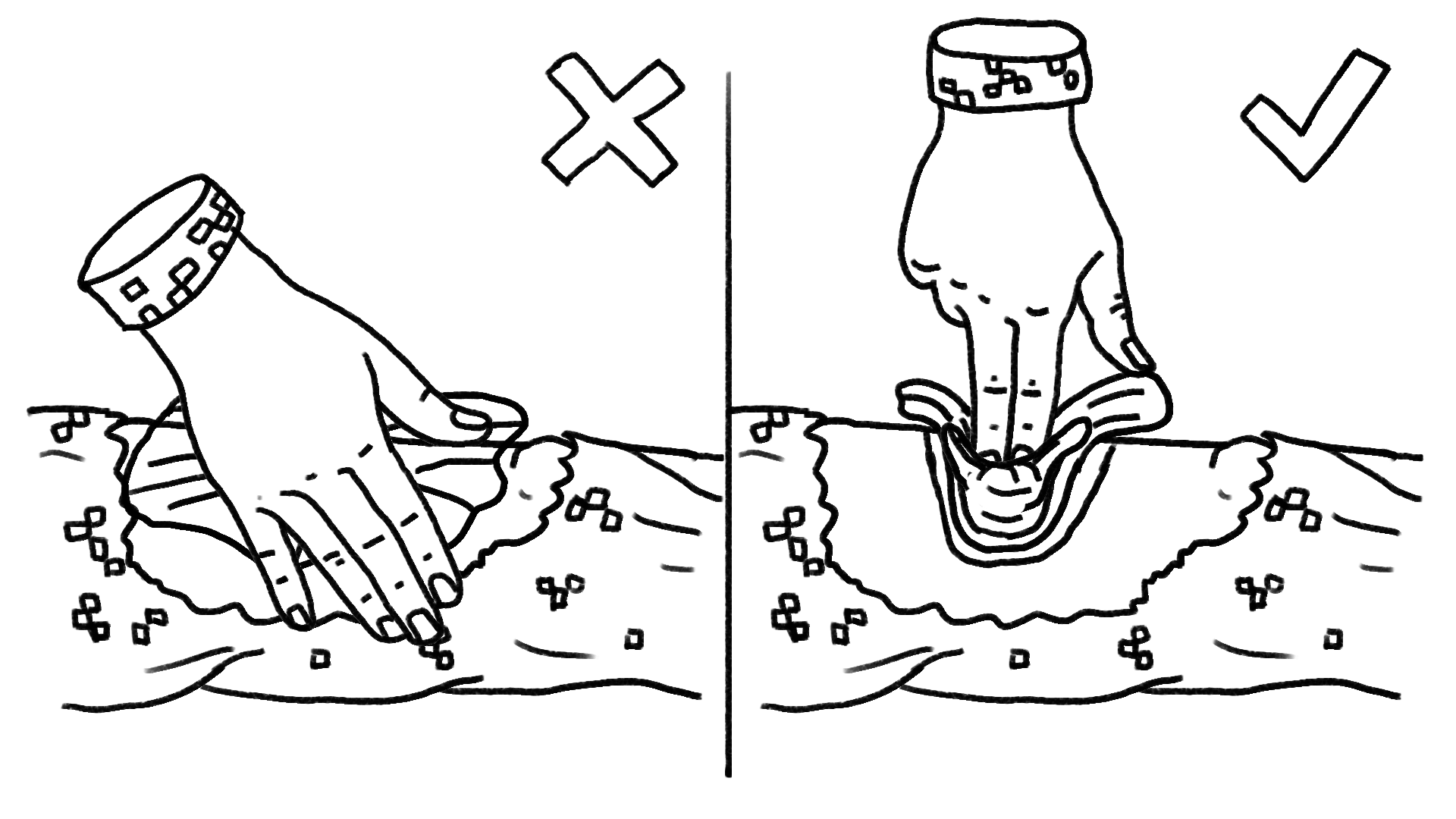

For instance they have this rule: “If you see a chest injury, call a doctor ASAP”. That’s great, but we don’t have evacuation helicopters to bring our wounded servicemen to a hospital in 10 minutes. With that in mind, we slightly adjust the programs and teach our people that they can tape a hole in someone’s chest with improvised means. We don’t use complicated words — they don’t have to know what pneumothorax or occlusion are. But they do need to know how to tape that hole.

What’s the procedure in general? What is the step-by-step guideline for a wounded serviceman?

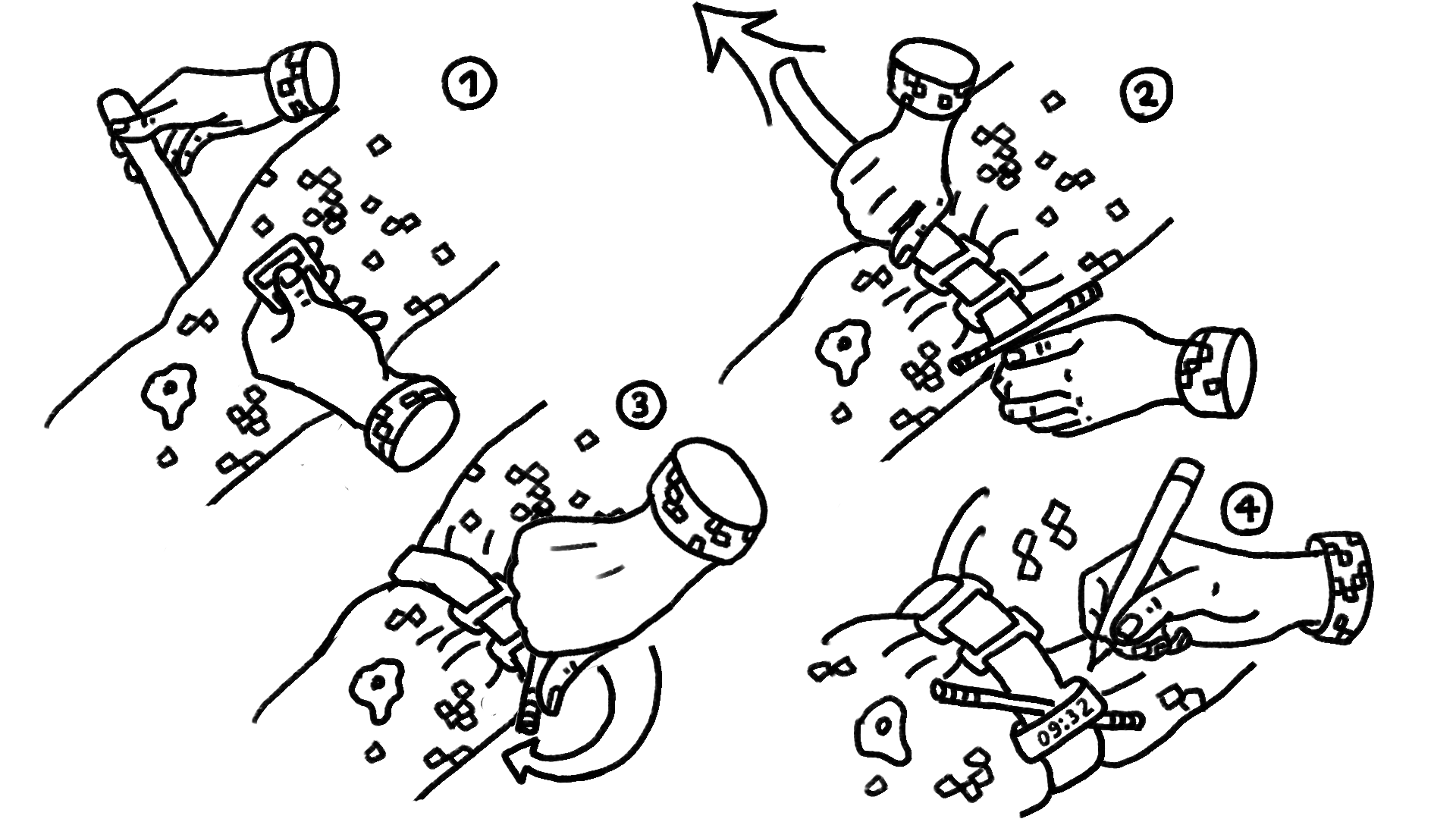

According to the instruction, they have to fire back, move to a shelter, and help themselves. First step is to apply a tourniquet. Then it’s usually their comrades or combat medics who give them further medical aid. The decision to evacuate is always on the commander, who can evaluate the situation. For instance, if the entire unit has favorable tactical positions, is located in a shelter or in armed vehicles, while the wounded serviceman is far away from the unit, evacuating him might put the rest of the soldiers in danger.

That’s why we teach people to treat every evacuation as a full-fledged operation, when you have to analyze and plan the number of people you will need, your backup and so on.

We had a case. We organized an evacuation-focused training for a unit, worked on different scenarios — with a car or without one, in a shelter or under fire, with a missile attack threat and so on. A week after training, they had a tough battle, almost everyone from the unit was injured or had a concussion. They had to evacuate themselves. Someone walked on their own, someone was dragged by their comrades. They all survived and wrote us thank-you letters for teaching them to do things right.

How has tactical medicine changed in these 8 years that you’ve spent in the Armed Forces?

Tactical medicine is finally not the last in line to receive funds. Because now everyone understands that we are talking about saving people’s lives. We’re now implementing Western protocols. Programs and first aid kits are changing all the time. Probably, everyone saw photos in russian publications with stolen Ukrainian first aid kits on them, followed by comments like “What’s that? Do Ukrainians take better care of their servicemen?”. Of course, we do.

Actually, everything has changed, because the army itself has changed. Now it’s not about a career when you sit and wait for a big pension. You can become a top-notch specialist in the army, you can do things that matter. Today, a motivated sergeant can even command a platoon, plan training together with the unit, or give some advice to an officer about operations. That’s how we differ from the russian army. I’m not going to say that things are flawless. But I’m also not going to say that things are catastrophic. I saw different things during my practice — top-notch first aid kits and those, where people had a “stick” instead of a tourniquet, or a bandage instead of a hemostatic. I also have to admit that our first aid kits are not 100% equipped, and volunteers have to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to provide us with necessary medical equipment.

I saw different things during my practice — top-notch first aid kits and those, where people had a “stick” instead of a tourniquet.

Speaking of volunteers. People on the home front keep raising money for tourniquets and first aid kits. Is it really necessary to support the combat capability of the army?

It’s a tough question. I can say for sure that we wouldn’t’ve made it without volunteers. On the other hand, I can’t help but think that this system would be more effective if it was centralized.

Sometimes help can do more harm than good. A “better-than-nothing” principle doesn’t work in medicine, because people can lose their lives due to the lousy tourniquets. Sometimes, people have money and motivation, but they lack qualifications and buy useless things as a result.

What’s the solution here? A single system, which gathers donations and distributes money and medical equipment?

Yes, in theory. Can one person or one organization purchase and distribute a million tourniquets? Yes, they can. If they have the right resources. But a lot of our funds and organizations would rather make a small, but personal donation. Even if it’s only 10 tourniquets and logistics expenses make up the significant cost of the parcel itself. Is this the most effective solution? It’s not.

But on the micro level this fund is what actually helps to defend Ukraine here and now. It’s what works in practice. When one person needs something, their community will move heaven and earth but find what’s needed. It’s the Ukrainian superpower.

What’s the most annoying stereotype about combat medics and tactical medicine?

On one hand, it’s exaggerated heroisation. On the other hand, devaluation. I’m slightly taken aback by people saying that the Armed Forces of Ukraine are gods. No, they are ordinary people who do their job. An old legend about Pyrohov comes to mind. Soldiers believed in his superpower so strongly that they brought him a severed head of their comrade and thought he would stitch it back on. It’s important to remember that the army consists of ordinary people, not superheroes with unlimited abilities. The same applies to combat medics — sometimes, we are powerless.

I’m also annoyed when people think that combat medics are someone from the home front. Once I received a comment from a woman, who said that we are doing the same as those who defend us. Thank you very much. We actually do the same as military servicemen. Do we shoot? Yes, we do. Do we dig trenches? Yes, we do, if necessary.

I’m annoyed when people think that combat medics are someone from the home front.

Is this the reason why you write a lot about your job and do it with humor? Is this black medical humor your protective reaction or what?

It’s just how I live. I see enough pain, and humor helps me deal with it. I write about my practice because I want to show people how it actually works. And also to warn or scare off those people who associate tactical medicine only with movie-like heroic deeds.

Sometimes people take basic training and think that they will start saving people’s lives in a week, with harnesses, pierced throats, ovations, and glory. But in fact these things can only happen in active war zones, where you receive wounded servicemen 24/7. In 90% of other cases people go to a combat medic for a pill. Headaches and diarrhea, that’s what it is. And people don’t get it. When there will be heroic deeds, they ask? And sometimes they don’t even know which pill to give. Under normal circumstances, we train future combat medics for 4 months, and there is a special part of the training dedicated to receiving patients. But now, of course, all these programs are cut short.

Except active war zones, where you receive wounded servicemen 24/7, in 90% of other cases people go to a combat medic for a pill.

Do you have any opportunity at all to carry on with your projects from your civil life?

Not fully, but yeah. I realize that it’s important to have something apart from war in your life, so I’m trying not to lose this connection. My next project after the “ReaniMetro” is to equip our trains with defibrillators.

You can’t save all the patients. How do combat medics deal with it?

I can only speak for myself. I see death as a part of my life, as a part of my work. All I can do is to work harder, learn more, so that in any given situation I’d be able to say that I did everything I could.

I don’t like this stereotype that all medics are cynics, that they feel nothing and have no empathy. Usually, things are quite the opposite: people choose this profession because they have a lot of empathy and want to alleviate someone else’s suffering.

Being a doctor, you can’t stay indifferente. Death is a part of your work, of course, but you can’t ignore it, when it’s happening right in front of your eyes. It’s just, when it happens again and again, you learn to grow a thicker skin, you learn to work with your emotions simply to live on.

Being a doctor, you can’t stay indifferente.

How do you plan your future during the war?

I have a training schedule, for what it’s worth. But everything can change so fast. So far, my planning looked as follows: in spring, I thought that summer was coming, and there would be mice, meaning that we might deal with rabies and that sort of thing. Got ready for it. And for the mites. In summer I think about fever remedies that we will need in autumn, because our military will obviously have the flu.

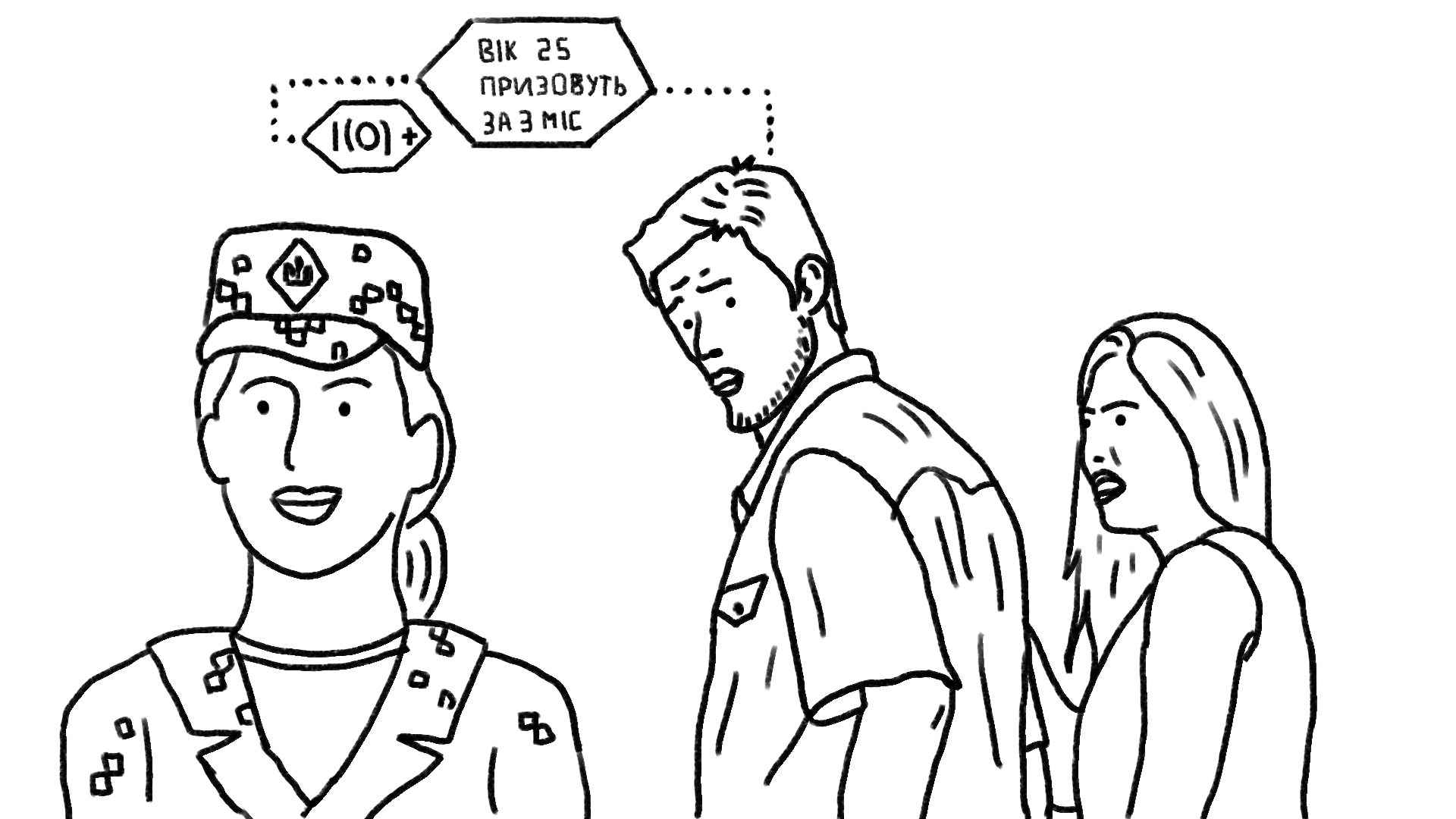

I’d recommend doing the same to those people who haven’t joined the army yet — you have to think ahead. I was in Kyiv recently, looked at people around and imagined labels over their heads like in a computer game: “Will be summoned in 2 months”, “Will be summoned in 47 days”. I see it, but they don’t. Obviously, if a person hasn’t joined the army yet, they have no desire to do so. But this is going to be a long war. And many will have to fight. And it’s better to get ready for this, research units that you’d like to join, get some basic training, don’t just sit and wait to be called in.

What’s it like to work in such a hierarchical structure that is the army?

Luckily, the Ukrainian army stepped away from the Soviet senseless hierarchy a long time ago. But there is still discipline and order here. Me personally, I think these things are crucial. You can’t build a teal organization in the army. If we listened to business coaches, listened to everyone’s opinions in the unit and then looked for a consensus, we would never finish a single operation. That’s why we have structure, borders, and responsibility. But it doesn’t mean that you can’t speak up against the arbitrariness and poor qualifications of your commanders.

You once said that activism is a kick democracy. Do you think we can still talk about building a civil society during the war? Is there time for this?

Yes, and even more than before. It’s important to have people who will keep a close eye on the “assholes list” while everyone else is inspired and focused on the war. Because this list is not getting shorter. We can’t tolerate corruption, schemes, or illegal construction because of the war. We can’t postpone these things. We’ve been through this already. People want to make the army responsible for everything. But the best people are already in the army. And not all of them are coming back. So let’s start thinking about the future that they are protecting right now.

Do you remember the time when you painted a red cross on your t-shirt and went to Maydan to save people. Have you ever regretted that call?

I do remember it and I never regretted it. I heard that when you say “I had no other choice”, you accept the role of a victim. It’s like you acknowledge that the circumstances were stronger than you. But it’s different in my case — it’s the opportunity to be complete.

Illustrations: Roman Krivenko

New and best