“Our War”: In Search of a Fallen Friend

Visual artist and photographer born in Portugal, raised in Macau (China). Studied photography at the Royal College of Art in London. Currently lives and works in the United Kingdom.

— I captured this project over the course of three years in Libya and other countries in North Africa. It’s a partially documentary, partially speculative investigation into the disappearance and death of my close friend, South African photojournalist Anton Hammerl, during the Libyan Civil War in 2011.

He and three other foreign journalists went to Libya to cover the clashes between pro- and anti-government forces. On April 5, just a few days after their arrival in the country, they were kidnapped by Gaddafi’s militias in the area of Brega. When Anton’s colleagues were finally released after two months, we learned that he had been shot on the day of the abduction and his body left in the desert. He is still considered missing. For the past ten years, Hammerl’s family and friends have unsuccessfully demanded that the governments of the United Kingdom, Libya, South Africa, and the UN investigate his disappearance.

In 2019, I decided to travel to North Africa. I gathered a team of like-minded people for the trip, as I couldn’t do this project alone. In Libya, I couldn’t capture everything I wanted, so we also traveled to neighboring countries.

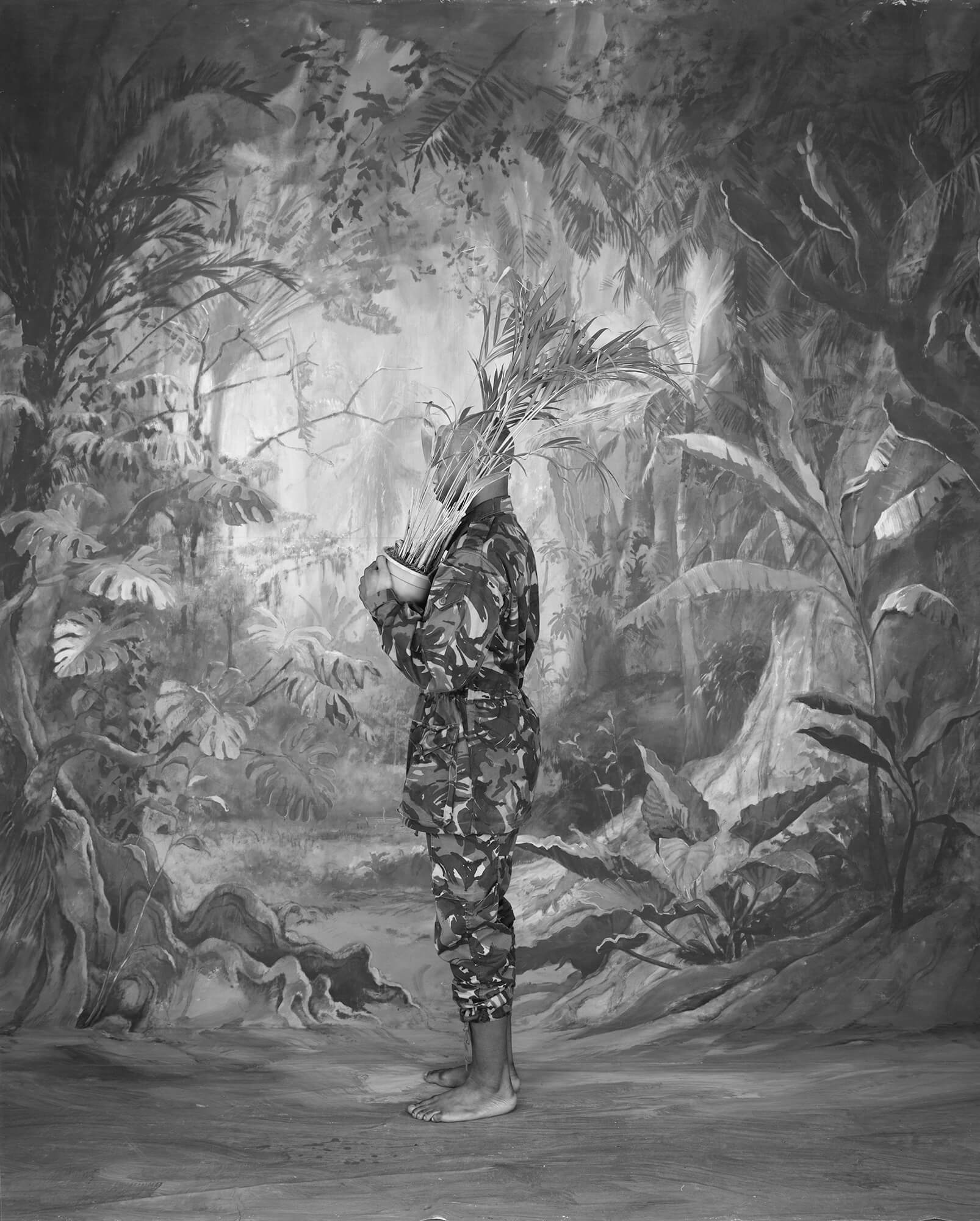

I quickly realized how difficult, if not impossible, it would be to conduct any investigation into Anton’s whereabouts in such an unstable place as Libya. So I decided to create a project based on a simple premise: how to tell a story when there are no witnesses, testimonies, evidence, or subjects? Moreover, how can one mourn the absence of all these things?

During our trips, I did not feel particularly unsafe, despite the fact that the tension was very high, as was the likelihood that something would go wrong. On the road, we constantly encountered law enforcement agencies, and once my equipment was even confiscated. However, I took all necessary measures to ensure that neither I nor my colleagues were in danger.

I retraced Anton’s path, spoke with those involved in the conflict (fighters or their descendants, freedom fighters, former Gaddafi loyalists, local residents, Libyan dissidents, and other people who did not directly experience the horrors of war but wanted to share their stories and bring them to life), found points of intersection between our journeys, and understood my friend’s motives. Thus, I was able to put myself in Anton’s position, if only for a moment.

I didn’t feel particularly in danger, despite the fact that the tension was very high and the probability of something going wrong was also high.

In the first 18 months of working on the project, I didn’t take any pictures. I was mainly interested in studying the geography of the country and meeting and talking with people.

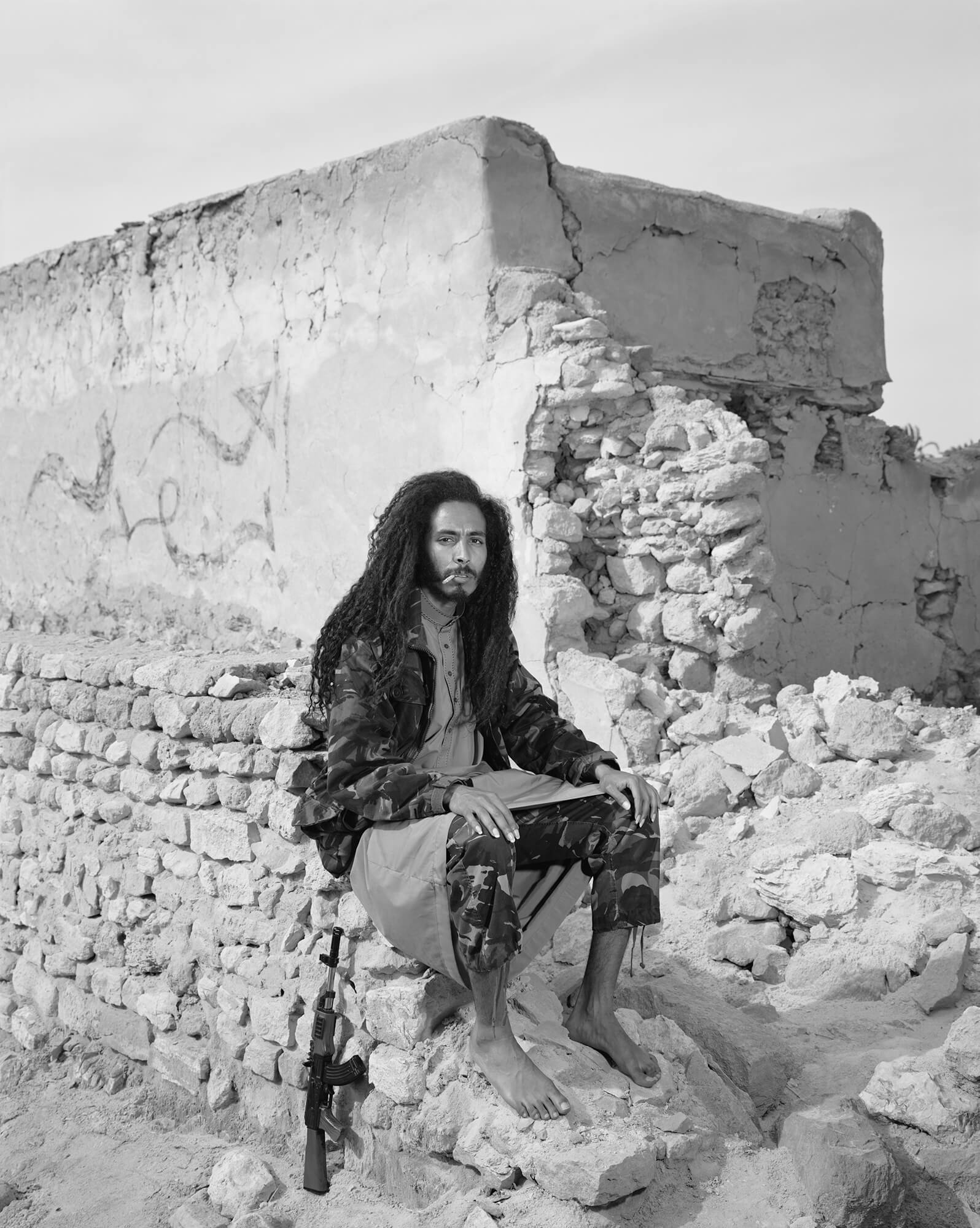

But when I started taking pictures, I realized that the portraits would have a performative character. This came down to a few things. First, I photographed people who had never been photographed before, at least professionally. Recognizing the imbalance in the relationship between the photographer and the subject, I decided to give them control. I set up a large format camera on a tripod, raised it to eye level and stepped away, leaving the subjects in front of it for a few hours so they could become familiar with the process. Sometimes we just talked about the project and didn’t take pictures. Finally, I photographed them as they imagined themselves on the picture.

Secondly, what has always concerned me about documentary photography and photojournalism is the tendency to deny, unintentionally distort, or blatantly exploit subjects and heroes. Photographers often create images that, in my opinion, only confirm certain stereotypes about specific subjects.

In war, we often see these tropes: the rebel as a good guy, the freedom fighter as an ideologue, the insurgents as bad guys, and the war as a polarity between aggressors and victims. But reality is always much more complex. Most of those who participate in the conflict do so not for ideological reasons. For some, it’s about money, for others, it’s a means of survival.

So, to distance the viewer from these stereotypes, I photographed not only people who were affected by the conflict or participated in it. I also photographed descendants of those who fought: they wanted to understand the trauma of their parents. We also involved local residents in the photo shoots to tell their own stories and hear theirs.

I chose many of my heroes based on how much they reminded me of Anton at various stages of our friendship. Some of these encounters had a cathartic and reconciling effect. And this made me realize that photographs should not be the ultimate goal, but merely a means to achieve it. A means of bringing people together and telling stories.

I chose many of my heroes based on how much they reminded me of Anton at different stages of our friendship.

With such an approach, the viewer can never be sure who exactly they are looking at. This not only eliminates the voyeurism usually associated with consuming such images, but also protects the identities of those with whom I have collaborated. Speaking for others in a certain way is not respectable. However, I am primarily interested in creating conditions under which people who may not have the right to vote can speak for themselves.

And finally, regarding the performative nature of these portraits: there is a real situation, and there is how I imagined this reality after learning of Anton’s death. In the absence of evidence, testimony, witnesses, etc., the imagined reality of the conflict, people, and circumstances surrounding Anton’s death was all I had. So I wanted these two dimensions to converge, overlap, and blur in my work.

My series is not a traditional documentary project. I was interested in exploring how to ethically and effectively tell the story of a contemporary conflict. In my opinion, photography often lacks this.

So this project is not just a tribute to my dear friend. It tells a complex story about the difficulties of documentation, testimony, memory, and imagination. It also explores new methods and techniques of visual representation of conflicts and traumas, introducing alternative approaches to responding to war, photographic ethics, and working with profound loss.

The visual part of the project is currently completed. What is not yet finished is editing and bringing together different aspects – the actual photographs and the archival work I conducted.

This project is not just a tribute to my dear friend. It tells a complex story that speaks to the difficulties of documentation, testimony, memory, and imagination.

In addition, I am preparing the first exhibitions of the project, which will take place next year. They will be immersive and mainly consist of audiovisual installations based on my photographs.

I have always been interested in determining the figurative dimension of our attitude towards photographs, particularly documentary ones. Therefore, the main goal of the future exhibitions is to question the viewer’s convictions and expectations.

I forgot who said it, but photographs, like language, are offered to us as a Trojan horse. We accept them as a free gift, but at that moment they capture us. Therefore, I no longer think that we know how photography works. We always demand too much from it, trying to learn the whole truth (which can never be precise), or too little as from a document. I am interested in exploring this further.

New and best