Hiding in Plain Sight: Closeted Ukrainian Gay

5-10% of the world’s population are representatives of the LGBTQ+ community. Ukraine is no exception, but only 14% of the country’s residents are accepting of their LGBTQ+ fellow citizens.

Ukrainian homosexuals and transgender individuals constantly face attacks, moral and psychological violence. Over the past decade alone, 1,861 crimes based on homophobia have been recorded (according to the “Nash Svit” center). In most cases, victims believe it is better not to turn to the police, fearing exposure, continued harassment, and lack of justice. And it is justified. For example, recently, several individuals tortured a transgender person in Zhytomyr. It has been a month, but the police have not pressed charges against the attackers.

Homophobia also operates at a more subtle level. On June 21st, during the Equality March (held online due to the pandemic), a drone flew over Kyiv with a rainbow flag. Within a day, the official KyivPride Facebook page’s video received over a thousand comments, the majority of which were homophobic. Particularly outraged was the fact that the drone briefly hovered near the Motherland statue, with many users interpreting it as a “mockery.”

Ukrainian artist and photographer. Based in Amsterdam, he works with themes related to LGBTQ+. His work has been published in Vice, BBC, Bird in Flight, Calvert Journal, GUP Magazine, Huck Magazine, Radio Svoboda, and Novoe Vremya. His exhibitions have been held in Ukraine, France, the Netherlands, Georgia, Germany, and Canada.

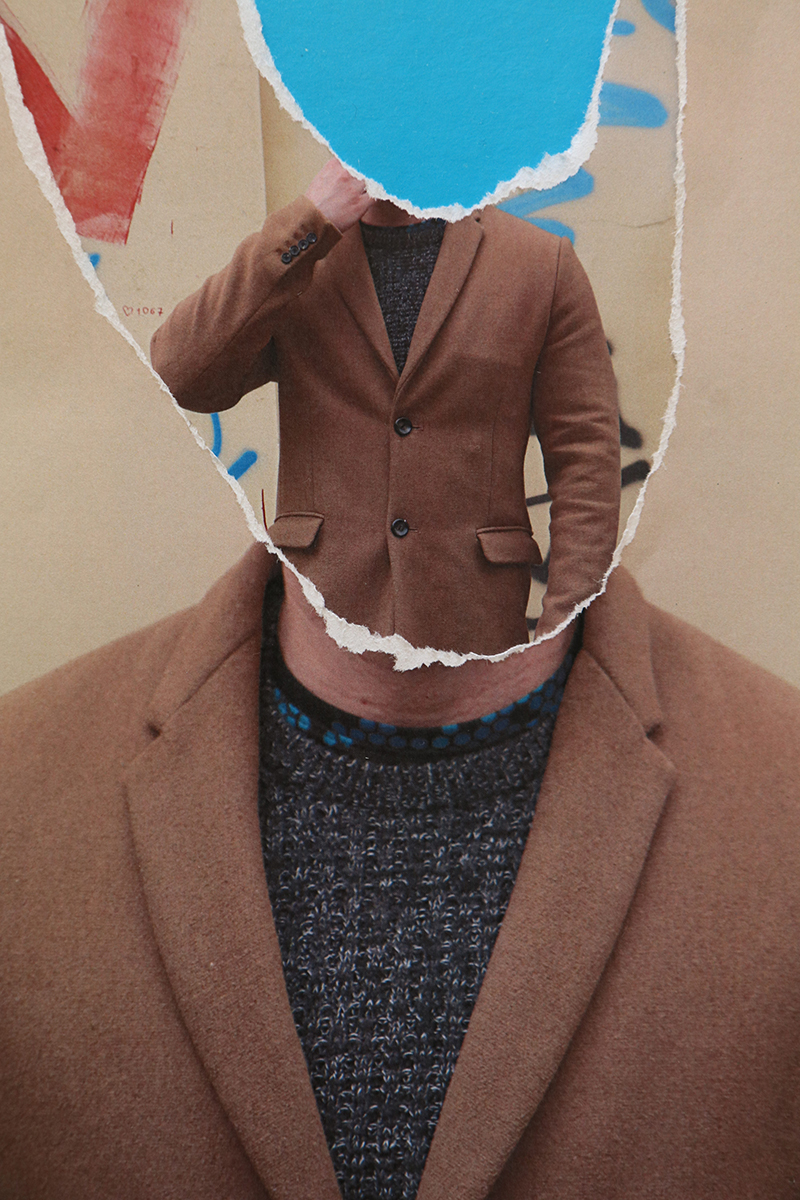

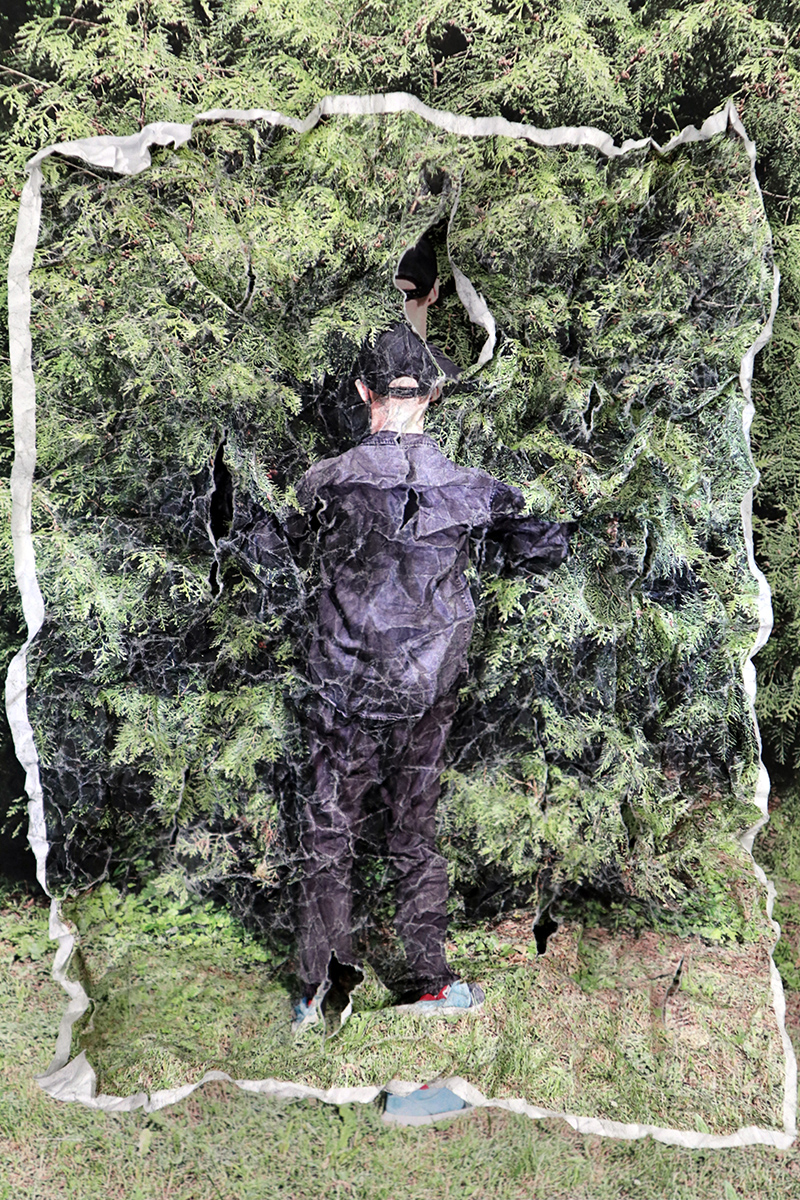

— The project is based on the desire to understand and depict the uniqueness of Ukrainian LGBTQ+ individuals (in this case, gay men) – their lack of coming out. This is a common and relatable experience for many of them. And it leaves an imprint on the works dedicated to the community’s life. Of course, there is always the option to approach activists and create a project about openly LGBTQ+ individuals, but it is important to understand that they represent only a small part of the community, the tip of the iceberg. I was interested in the majority and how fear restrains them. This story can be perceived as an autobiography. In the initial version of the project, my portrait was included.

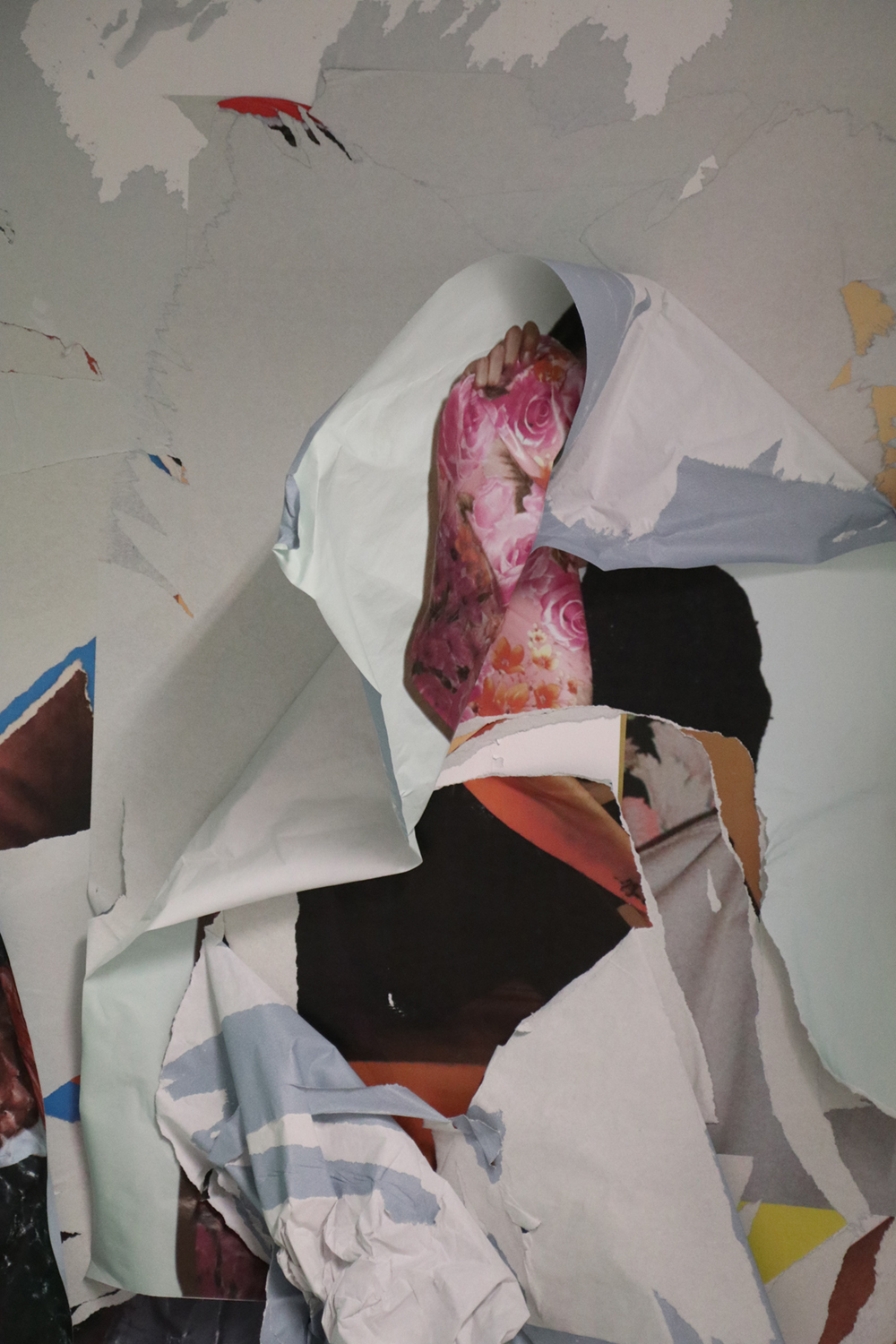

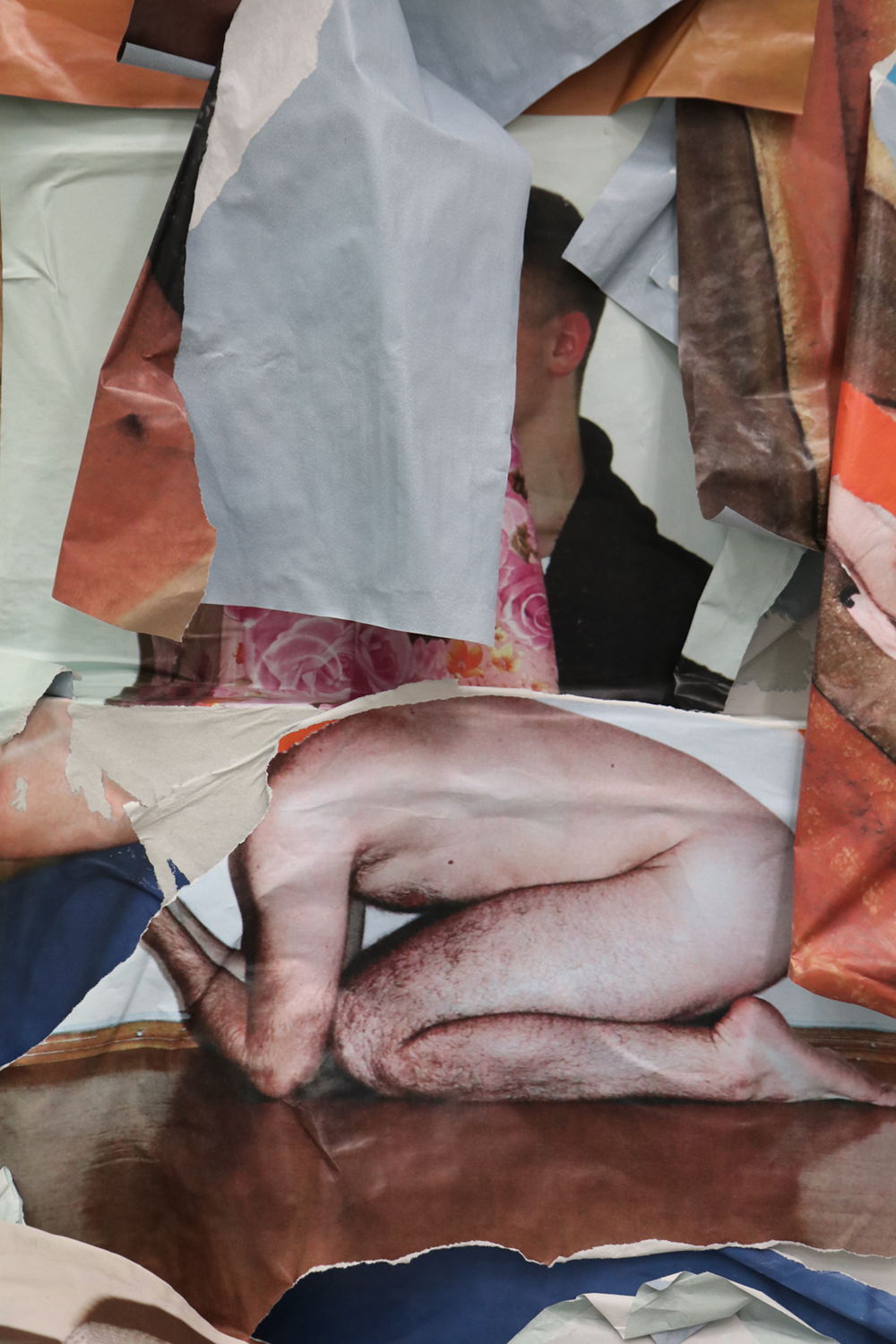

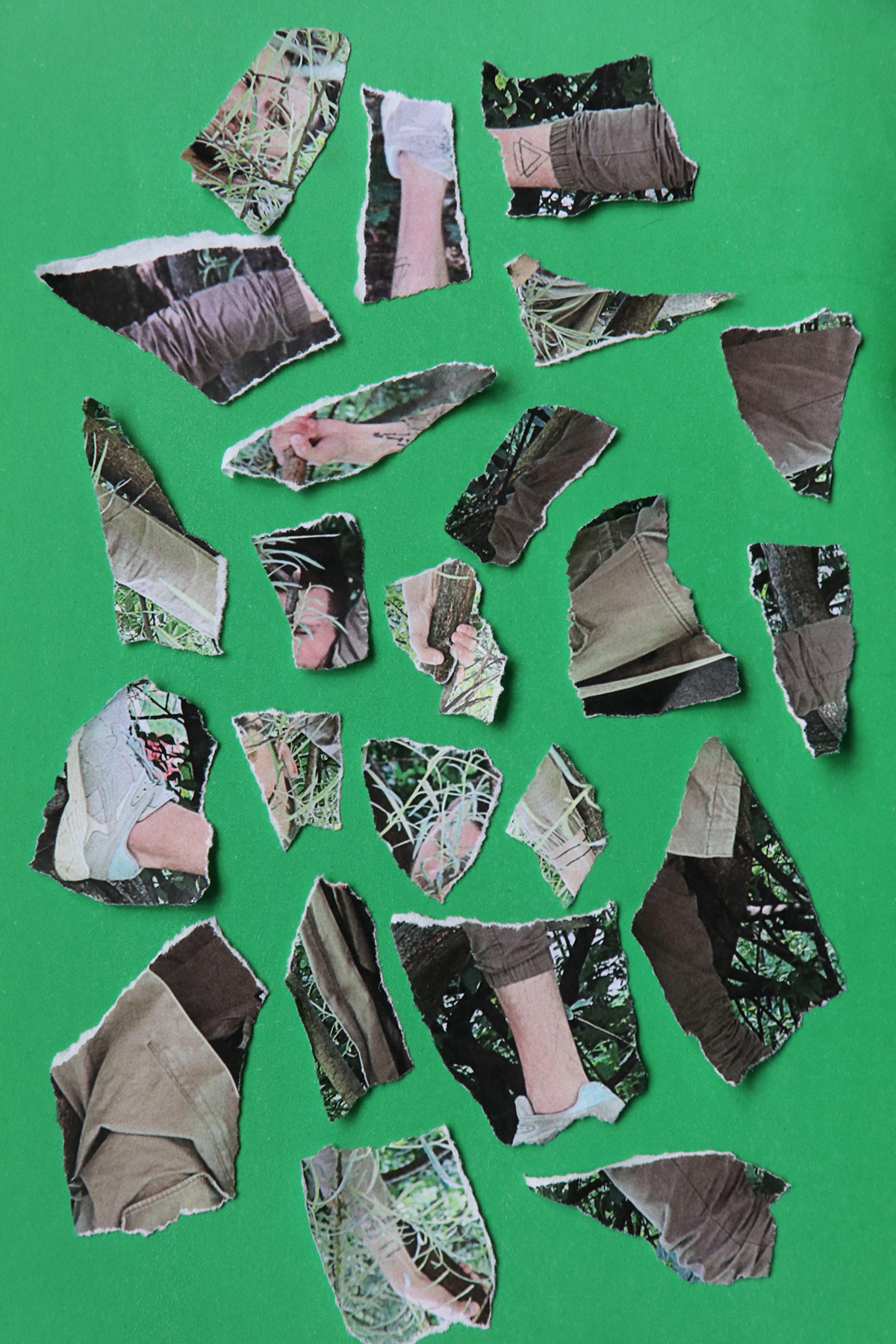

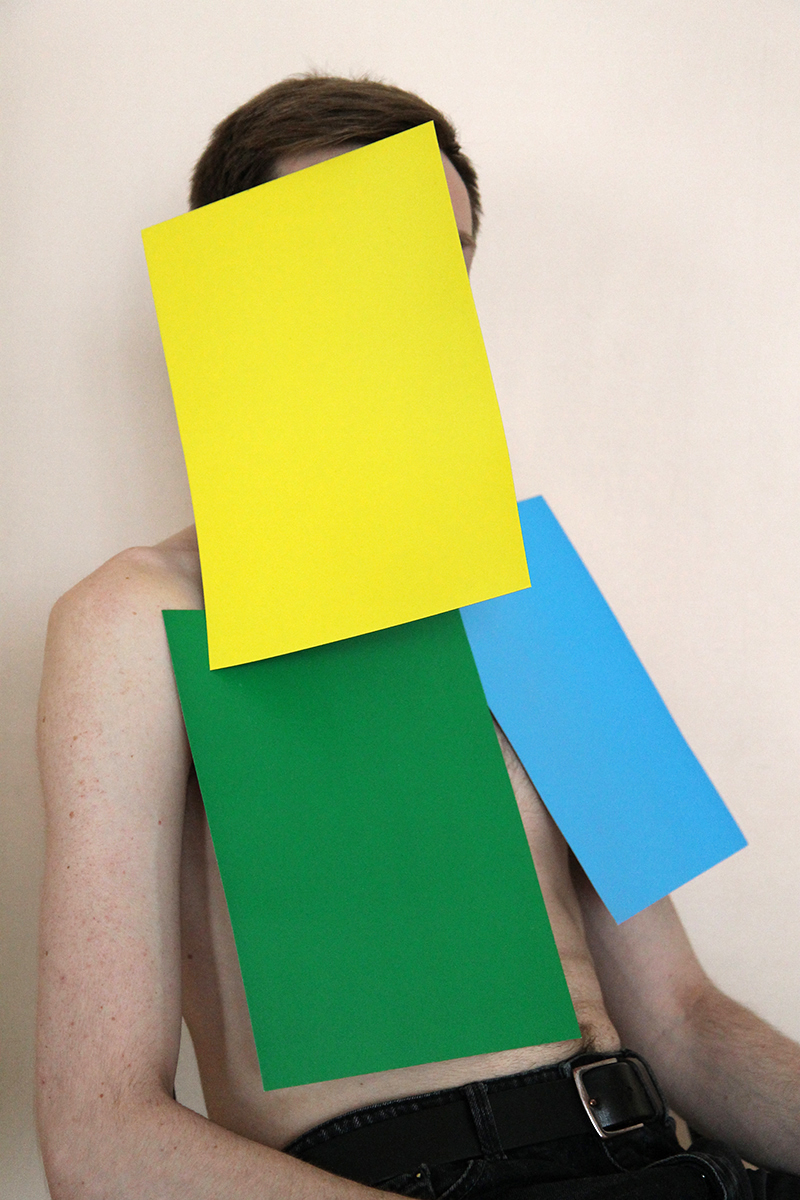

I chose the portrait because it is a genre of photography that requires honesty and openness from the subject. All the portraits are anonymous: I printed the photos and tore and crumpled them so that it would be impossible to “recognize” the individuals. The destruction of these images is a consequence of the inability to fully express their truth, a narrative of “invisibility.”

Overall, I captured around 50 portraits, but there could have been more. I initially asked people from my immediate circle to participate, and then friends of friends joined. Many friends declined, fearing that they could somehow be identified. Most refusals came from the older generation – some of these individuals are in heterosexual marriages, some have children. Their family members are unaware of their orientation or prefer to maintain such an appearance.

The story of coming out (or more often its absence) is a popular topic of conversation among the LGBTQ+ community. It’s easier with friends because you can choose a social circle that accepts you. The main places where people don’t disclose their orientation are family and work, where they have to endure.

Based on my observations, fear is inherent in almost all Ukrainian LGBTQ+ individuals. And it’s not the fear of physical violence, although such cases regularly occur, but rather the fear of non-acceptance, mockery, and ridicule. This fear pushes hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians to live their lives in total deception. They all grew up in a heterosexual majority, with heterosexual parents, surrounded by heterosexual friends, relatives, and colleagues who often hold discriminatory views towards different orientations.

I conducted interviews with all the subjects, asking why they don’t come out, how they feel about Pride, and if they have encountered homophobia (these interviews will be part of the book I am currently working on). Almost all of them have faced homophobia. Some were fired, some were harassed by the police, and some were rejected by friends and parents. If the subjects didn’t reveal their identity, homophobia wasn’t directed specifically at them, but it didn’t disappear either: widespread jokes, calls for lynching, demands for banning and wishes to “cure” are still perceived by LGBTQ+ individuals as aimed at them. Many of them internalize these views and suffer from internalized homophobia.

When you tell a European that you’re gay from Ukraine, they look at you with sympathy. A huge number of Ukrainians seek and obtain refugee status as LGBTQ+ individuals.

And this diagnosis applies to the entire Ukrainian society: we are seen as savages who beat and kill fellow citizens because of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or nationality.

We are to blame ourselves for the reputation of being savages in our country. Populist politicians, catering to the most conservative segments of society, regularly try to pass laws “against the promotion of homosexuality.” We lack effective laws that would counter workplace discrimination, and homophobia is not considered an aggravating circumstance in cases of assault. Coming out is not about self-acceptance; it’s about survival.

We are to blame ourselves for the reputation of being savages in our country.

Of course, homophobia exists in the United States and Europe, which are often considered as benchmarks. However, they would not try to classify a knife attack to the heart as mere hooliganism. You cannot be fired there simply because you have a boyfriend waiting for you at home instead of a girlfriend. Not to mention that in countries that Ukraine looks up to, same-sex partnerships and marriages are legal, and such couples can adopt children. These are basic human rights that should be accessible. They are about dignity.

Traditionalists who advocate for curtailing the rights of the LGBTQ+ community promise eternal values and a blessed world. But we should not rely on that. The hatred they foster, consciously or unconsciously, towards their own brothers, sisters, children, and parents will never be a driver of progress. Instead, it will only further alienate us. To become truly human, we need to understand that there are people around us, and they all deserve the same rights without reservation.

I don’t have the right to urge or demand someone to come out. I understand why many people in modern Ukraine choose not to do it. A life in which you have adapted and resigned yourself to the hardships may be better than a life in which you are killed. But the complexity lies in the fact that without visibility, nothing can be achieved, and without a fight, there can be no victory. The desire to soften the sharp edges is an option, but it comes at the cost of not fully living your life.

A life in which you have adapted and resigned yourself to the hardships may indeed seem better than a life in which you are killed.

On the other hand, coming out is not as terrifying as it may seem. In contrast to tragic cases, there are numerous examples where the decision to come out has resulted in positive outcomes. Some of the project’s heroes have come out, and as far as I know, they are doing well: they are living in harmony with themselves, and the people around them have suddenly realized that LGBTQ+ individuals can be among their relatives and friends.