“After 18 Hours in the Kitchen, Nothing Is Difficult for You”: Olia Hercules — on How Food United Ukrainians and Britons

Olia Hercules is from Ukrainian Kakhovka, but she moved to Cyprus as a teen, then studied in Great Britain, and went on living in London. At first, she tried her luck in journalism, but then she studied to become a chef and started working in restaurants and catering. But Olia also published as a food author and soon began writing cookbooks.

Her first book ‘Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine & beyond’ covering Ukrainian cuisine recipes came out in 2015, it was then followed by ‘Kaukasis’ with recipes from the Caucasus countries, and ‘Summer Kitchens’, which explored the phenomenon of summer kitchens in Ukraine. She also organized expeditions to Ukraine for foreigners, where they visited those summer kitchens and learned authentic recipes. The last book, ‘Home Food: Recipes to Comfort and Connect’, was published in 2022.

At the beginning of the Russian invasion, Olia Hercules became a co-founder of the charity project ‘Cook for Ukraine’, in the framework of which chefs from all over the world prepare Ukrainian dishes and collect money to support Ukraine.

Tell me about your initiative Cook for Ukraine. Who did you manage to involve and how much money did you raise to help Ukraine?

At one of the Ukraine supporting campaigns, my friend Alisa, also a chef, suggested that we do something together. We were familiar with the people who came up with a similar Cook for Syria project, so we turned to them for help and later launched Cook for Ukraine together. At the same time, I was also working on bulletproof vests, helmets etc., because my brother in Kyiv joined the Territorial Defence Forces and sent a photo of him with barely any protection and a machine gun.

So Alisa and her team started promoting this hashtag #CookForUkraine. The idea was for people to cook Ukrainian dishes and share them on social media. We understood that in the first months everyone would still want to help us, but then they would get tired. We thought that Ukraine, at least in this way, would pop up in the social media and in the minds of Westerners.

Within a month, there were already 10,000 hashtags, and 200 restaurants in London alone started preparing some Ukrainian dishes and donating. So we raised more than 2 million pounds. We decided to support UNICEF, because everyone knows it, but we also asked to donate to some small volunteer organizations.

Even we did not expect such a result: restaurants from Spain, from Australia, from everywhere in the world joined. And not only restaurants – even schoolchildren made some Ukrainian delicacies and sold them to raise donations.

It is clear why foreigners are now interested in everything Ukraine related. But even before the invasion, you published books with recipes of Ukrainian cuisine and brought Europeans to Ukraine on food tours. How did you get them interested?

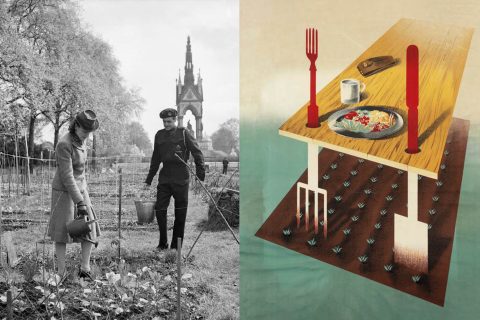

In England (in other countries as well, but here it is especially noticeable), somewhere in the 2010s, everyone began to value high-quality homemade products, to try to cook in a way so that nothing was thrown away. For them, it was just a trend, and for Ukrainians it was a part of culture and life. There was a kind of synergy between what the chefs in England did and the people here. For example, fermentation has become popular here. Of course, things are perhaps a little different in big cities now, but my mother in Kakhovka and in general people in the Kherson region still do all these pickles, grow tomatoes and so on. That is why I think that the British were interested in the fact that behind all these trends we have a lively culture and history. This is one of the reasons. I also like to believe that Ukrainian dishes are just very tasty.

Besides, the thing is the way I wrote ‘Mamushka’. I had a lot of stories in the book. Now you can find any recipes on the Internet, so I added human faces to them. This is how the British learned that Ukraine is big, we have regions, we have regional cuisine, rich history and traditions, which we are now reviving. So I hope they were also interested in this human story of ours.

Now you can find any recipes on the Internet, but I added human faces to them.

By the way, when my brother sent me that photo with the machine gun, I raised 130,000 GBP in donations for him and his sworn brothers on Instagram in two days. Even people who know me only through books and Instagram sent money. And I think that it is thanks to the fact that there were not only recipes in those books, but also that I also talked about my family.

It seems like there is a gastronomic trend in Ukraine – for the “decommunization” of the kitchen and the search for authentic recipes. For example, all these alternative recipes for New Year’s dishes, so as not to cook olivier. What do you think about it?

Yes, there is such a trend, and I believe that it is very important, especially now. But good God, if someone likes olivier, let him eat that olivier. It is also a dish of my childhood, and when I eat it, I don’t think of the Soviet Union, I think of my mother.

And yet it is very, very important to do at least some personal research, that is, talk to grandparents, other relatives, neighbours and literally ask: “What dish did your grandmother or mother cook, and you no longer cook it?”. This is the first question I asked people during our summer kitchen expeditions.

So, in Polissia, we drove into a small village where there were almost no houses left. We found a cool family, where grandparents lived in a summer kitchen, and they told us that they used to make borscht with eels, small ones, like baby-eels. You won’t find that in any book. But these eels became extinct in this area, so the borscht also disappeared. This is how the Soviets created disasters – they dried up rivers and built dams. This is what we need to explore while these generations are still alive. This is our last chance.

And what should we do with this borscht? I mean, on the one hand, this is the most banal thing you can tell a foreigner about Ukrainian cuisine, so maybe you should switch to something else? On the other hand, UNESCO has already recognized it as a heritage, and there are many recipes for borscht.

You just have to accept that borscht is very diverse, and be proud of it. Yes, in Italy or France they are very proud of their regional dishes and the fact that in some other region it is prepared differently, it is interesting. We also have to find more specifically regional features.

You just have to accept that borscht is very diverse, and be proud of it.

For example, Tavria, where I grew up, also has its own borscht. It includes a rooster, and a large dumpling made of sourdough is inserted into it. They also prepare leok, a sauce with garlic and dill. And my friend’s grandmother from Kakhovka used to make borscht this way: she dried fish and tomatoes, ground them in a mortar and added them to borscht. These flakes of dried fish and tomatoes seem like something Japanese.

What else so unusual did you find during your expeditions, besides borscht?

For example, in Poltava Oblast, they make apples in pumpkins. Everyone eats apples, and I was also interested in this fermented pumpkin purée – I make sauces with it, add a little chilli and salt to it. Because traditions are good, but they must be adapted.

In your opinion, are there enough projects or specific chefs in Ukraine who popularize Ukrainian cuisine within the country?

Yes, there are many of them, actually. Of course, Klopotenko has the most media coverage, but I know chefs from Kharkiv, Odesa, and many from Kyiv. But I would be interested to see someone who is not from big cities.

My dream is to create a culinary school on the liberated territories as we rebuild them. To build a typical Ukrainian house, maybe even with a stove, so that teenagers and other people after school can study there for free. For children to learn how to grow vegetables, how to cook sourdough bread. It’ll be cool even if they don’t become chefs, but it’s therapeutic and important to keep traditions alive.

Perhaps you then researched the state of culinary education in Ukraine? Is there a place for people who would like to follow this field of study, or do they mostly go to foreign schools?

I didn’t research deeply, maybe there are good schools, but I mostly heard about master classes of foreign chefs. It would be great if more local chefs could train the next generation.

Is it difficult for a Ukrainian to go and study at some European culinary school? What might be the obstacles?

Perhaps the main thing is that it is quite expensive, and knowledge of the language may also be an issue. But right now, it’s a pity that it is due to such sorrowful reasons that there are more opportunities for Ukrainians, because, for example, it is easier to get a scholarship.

Let’s say you are a Ukrainian, found a culinary school abroad, received a scholarship, studied, and then you want to work. Will it be difficult to find a job? Let’s say in London.

Previously, the biggest problem was getting a visa that would give you permission to work, but now Ukrainians are given such visas right away. There are also many local volunteers who help you get a job. And the English themselves are trying to support the Ukrainians, so I think it is not very difficult now.

When you were looking for your first job in the culinary field, this kind of support probably wasn’t there. How did you manage to succeed?

At first, I generally worked as a journalist, I got this job just like everyone else: you simply come to some editorial office after university and work for a long time for free. Unfortunately. I did this internship for about a year and a half. Then my parents supported me and helped me learn to be a chef, while I still worked on Saturdays – washing dishes after culinary workshops. As soon as I finished my studies, I immediately went to work in a restaurant with 18-hour shifts two or three times a week. Restaurants usually have a shortage of cooks, so actually finding a job is not that difficult, but the work itself is very challenging. It was especially difficult in winter, because at six in the morning you already have to be at work. At that time, I prepared breakfasts – and from eight to twelve you cook for about 105 tables, and then until one in the morning you make pre-made food for the next day.

I worked like this for about two years, then I got pregnant and could no longer continue in this mode. Then I started freelancing – catering and the like, took up any job.

So it is good when parents support and help you study, but after all, you still remain alone in this London. It was very difficult, I won’t even try to romanticize the experience of 18-hour shifts, I cried. But I liked this sphere so much in spite of everything. Here they bring you a box of chillies that you have to finely chop, and you work it out for three hours. However, somehow you turn it into an almost therapeutic process. And then after these 18 hours of work in the kitchen, nothing will be difficult for you.

I won’t even try to romanticize the experience of 18-hour shifts, I cried.

Usually, the career of a chef is really thought of somewhat more romantically — that you are constantly inventing some new dishes, and not methodically repeating the same thing. Perhaps many people may be disappointed because of this?

When people ask me for advice on whether to quit their job and become a chef, I advise them to immediately go and work in a restaurant like this for a while. And if even after that you don’t say, ‘That’s it, I don’t want to cut that onion anymore’, then, of course, give it a try.

How did you make the transition from actual cooking to writing cookbooks? Did the experience in journalism or something else help?

That experience helped a little, but I was, in one way or another, always interested in history and literature. I would say I am a humanitarian. And then I realized that in my family, this tradition of telling stories has always been very strong, and also related to food. There were six children in my mother’s family, and they all met every year in Liubymivka, near Kakhovka. Mother and grandmother cooked a lot, everyone sat at the table beside the summer kitchen under the walnut tree. They discussed something while dining, told stories. Such meetings were so etched in my memory, because everyone was a great storyteller, speaking with emotions – we both sobbed and laughed. All this culminated into the fact that I became a writer.

When I finished my “Mamushka” and sent it to the publishing house, I thought that I wrote it as I could – with stories about a goose, about an uncle, about noodles – and that they will edit it all normally, rework it as needed. But they didn’t change anything. They said: “You have a great voice, it’s very authentic.” And then I realized that I have a “voice”.

When I sent “Mamushka” to the publishing house, I thought that they would edit it all normally. And they didn’t change anything. They said, “It’s very authentic.”

The British book publishing market is certainly quite competitive. How do you manage to sell your books, and especially how did you manage to do it with the first one especially?

The first book is, in fact, the most successful one. Although there are indeed as many cookbooks on the market, everyone publishes something here. So, in fact, now it has become much more difficult to somehow popularize your book. And “Mamusia” was released seven years ago with about 200,000 copies sold, that’s a lot. It has been translated into nine or ten languages.

Why was it so successful then? Did it happen immediately or over time?

Immediately. I think that what I told about the current trends in England and the relation of Ukrainian cuisine to them played a trick here. The second factor is that the war had already started, and many people became more interested in Ukrainian culture. And food is a very popular thing, everyone eats, so many stories can be told through it.

Another probable reason is that our culture is really cool and bright. And Ukrainian cuisine is not only potatoes and boiled cabbage, as some people think.

When I wrote “Mamushka”, I wanted to show that we have seasons, that in the summer there are tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, fermented watermelons. So many colours, so many techniques that differ from the European ones. So it seems to me that the British found in this book both something clear to them and something a little exotic. For example, one chef made a dish in his restaurant – pigeon with pickled tomatoes. And he tweeted that he found a recipe for the tomatoes in my “Mamushka”. How cool it is that they combined these English pigeons with our tomatoes. Then I began to notice that London restaurants everywhere started making these pickled tomatoes.

You are also a food stylist. Did you learn this in the process of preparing the book?

Even before that, because I like that you can not only cook, but also do various things alike.

And the first book had an interesting story to it. I got a call from a literary agent who had seen my recipe posts and asked me to meet and discuss a potential book. I came and for two hours talked about myself, my family, Kakhovka, and everything else. She says: you’re great, but you don’t have enough Instagram followers, because I had 500 at that time. She said, ‘Come back in a year or two, when there will be more social presence’. I left, but decided to start doing something right away. In England, they do it this way: food stylists who are just starting out, as well as photographers who were assistants and want to work independently, arrange a shoot together. The stylist buys all the products, cooks, and the photographer provides the studio and his time. Then they both use these photos for their portfolios and that’s how they find projects.

So I started to offer all the photographers I know to do a “Ukrainian food shoot”. God, how many people said no to me. They thought that there would be just potatoes there. And only one agreed and took great pictures. Then I prepared a book proposal in order to get a contract from a publishing house – it’s something like a thesis, which already has all the names of dishes, some recipes, some explanations, and a marketing part. But not only did I do the main thing, but also added these photos. And when they saw them, they were shocked at how cool it looked. That’s how we made “Mamushka”.

I started to suggest all the photographers I know to do a “Ukrainian food shoot”. God, how many people said no to me.

What role do you see yourself in now?

I can’t bring out anything or give up anything. Of course, you have to find balance, but I’m interested in doing different things. I will definitely continue writing, I plan to dedicate the next book to the regional cuisine of Ukraine. Because the Russians want to destroy us, and I have a mission to prevent them from doing that.

Did you plan on writing a book about Ukrainian cuisine specifically for Ukrainians?

I am not sure if I know well what Ukrainians need. I have two pairs of eyes: one from that girl from Kakhovka, and the other — from the West, because I have been in Britain for 20 years. Therefore, I understand well what is interesting here. So, probably, Ukrainians living in Ukraine will do it better. For example, Katria Kalyuzhna knows a lot about the Kherson region, and I hope that someday she will write a book.

Photo: Taras Bychko, specially for Bird in Flight.

New and best