A Place Under the Rising Sun: How Japan Hosts Ukrainian Refugees

In 1981, Japan has signed the UN Refugee Convention, which prohibits any kind of discrimination against foreigners, who seek asylum outside their country. Nonetheless, the Japanese immigration law is far from loyal. To receive refugee status, foreigners must prove that they are in danger in their home country and provide several witness testimonials to support their claim. The procedure usually takes up to 4 years. УDuring this time, a person is basically accommodated in a detention center under guard. But apparently, the war in Ukraine can change Japan’s attitude towards refugees.

Japan joined sanctions against Russia during the first days of the invasion, which, according to Bloomberg, was “unprecedentedly fast”. The Japanese government froze the assets of Russian individuals and entities and deprived Russia of the most-favored-nation status. The decision was strongly supported by society. According to the Nikkei newspaper survey, half of the Japanese approve of sanctions, and another half thinks that sanctions should be strengthened.

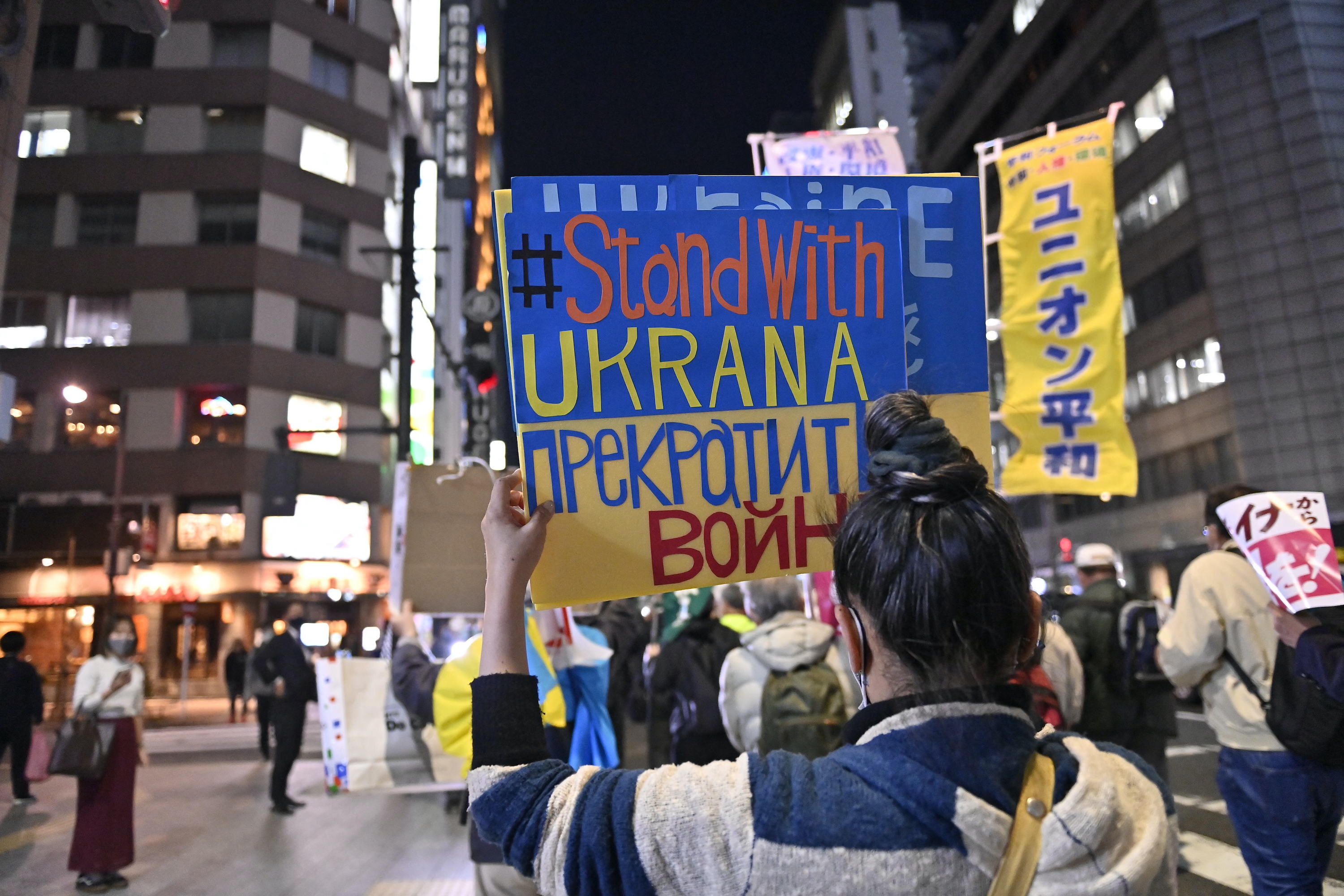

The Japanese protest against the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the streets of Tokyo. May 8, 2022.

Photo: David Mareuil / Anadolu Agency via AFP

Japan’s support of Ukraine was not limited to sanctions only. At the beginning of April, the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs, Yoshimasa Hayashi, announced that relatives and friends of the Ukrainians, who live in Japan, are welcome in the country. He himself fled to Poland to pick up Ukrainian refugees and fly them to Japan on the governmental Boeing 777. Besides, the Japanese government provided refugees with several flight seats on the regular commercial flight from Poland.

A special program to support the Ukrainians was launched. On their arrival in Japan, they receive a 90 day visa. After that, they have the right to apply for a year-long visa. Ukrainian refugees also receive one-time financial assistance of €1,200 and regular financial aid of $19 per day (for those, who don’t have relatives in Japan). At the end of May, the Ministry of Labor announced financial grants of up to 600, 000 yen for those companies, which hire Ukrainians. Tokyo and Osaka offer consultation centers for the refugees.

With that in mind, more than a thousand Ukrainian refugees have come to Japan since the beginning of the war. To compare, last year the Japanese government provided asylum only to 74 refugees from different countries.

Ukrainian students of Japan’s economic university wearing kimonos at the event dedicated to Fukuoka’s Japanese culture.

Japan’s loyalty to Ukrainian refugees is astonishing. According to the above-mentioned Nikkei survey, more than 90% of the Japanese think that Ukrainian refugees should be welcomed in the country, and only 4% spoke against it. According to the local activists, who favor easing the immigration law, the main reason behind this significant support is that the media actively covered the Ukrainian-Russian war. The Japanese saw the suffering of the Ukrainian people and understood that they needed help.

Bird in Flight talked to the Ukrainian, who arrived in Japan at the end of March, and found out what it is like to live in a country, which is learning to be kind to refugees.

Born in Kyiv, now lives in Fukuoka

— I came to Japan at the end of March upon the invitation of Fukuoka University. I’m exempted from the army, so they offered me to flee Ukraine and to live and study at a Japanese university for foreigners for free. I got my visa in two days. The only problem was that it was a tourist visa. Getting a student’s visa would have taken me up to a month. I also had to pay for the airline tickets. That cost me $1,300. To get to Tokyo, I had to make two transfers — in Poland and Germany. On my arrival in Japan, I applied for a student visa to get resident status. My university handled the paperwork.

Now I live in a dorm. The conditions are quite good: I have my own room, a bathroom, and a toilet. Accommodation and food cost around 40, 000 yen (approximately $320) per month, which is covered by the university.

If I break the local laws, the university can annul my student status. It’s a normal practice for Japanese universities. Their reputation means a lot to them, and they don’t want students to ruin it. For instance, alcohol is not allowed in dorms and on university premises. Students can also be expelled for working in cabarets, strip clubs, or casinos. Ukrainian students were involved in some minor incidents, but none of them were ever expelled.

Ukrainian students during the entry ceremony, Institute of the Japanese language, Osaka. April 11, 2022.

There are statistics, which claim that 85% of the Japanese are monitoring the war in Ukraine. It seems to be true. Local newspapers publish Volodymyr Zelensky’s portraits on a regular basis, and news about Mariupol was on all channels. One time, I was in a hospital and saw a news report about people in Mariupol hiding from shelling.

The war in Ukraine made the Japanese worry about their own aggressive neighbor, China. No one knows what to expect from the Chinese government. My professors and some other people tell me that now it’s a chance for Japan to take the Kuril Islands back, while the Russian army is involved in the war with Ukraine. This is a hotly debated topic in the local press. According to a Tokyo newspaper, 70% of the Japanese think that the Kuril Islands is Japan’s unfinished business. Those are mostly elderly people, since the youth don’t feel that strongly about the issue.

I can feel that the Japanese are quite interested in our cuisine and our cities. They ask me, how much does it costs to fly to Ukraine, and are the Ukrainian girls actually as beautiful as they look on the internet. But there is no fashion for all things Ukrainian here. Japanese are too restrained for that. Still, one can find interesting manifestations of support for Ukraine. I’ve been to a bar, which serves shots called “Glory to Ukraine”. The owners assured me that half of the revenues from those shots go to the Ukrainian armed forces.

Cover photo: Members of the Japanese-Ukrainian Cultural Association in Ukrainian traditional costumes. Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture. April 23, 2022. Photo: The Yomiuri Shimbun

New and best