Fall Three Times a Year:

The Day-to-Day of Traveling Winemakers

Spring in Europe, and in New Zealand’s wine region of Marlborough Valley, autumn. For winemakers, it is now the peak season of activity: harvest.

During this time, large wineries, require ten times as many employees for this task. Candidates with experience and an academic background in winemaking are sought after first, while wayward travelers looking for work and adventure fill in the remaining spots, often at the very last moment.

Last year in March, I found a temporary position in a New Zealand winery, to go to the other part of the world, to have a break from office life, to work on my English and to earn an incomparable salary to those offered in Kiev.

It was three months, two weeks, and four days of twelve-hour shifts, seven days a week, and ten thousand tons of grapes, which me and my thirty colleagues had to turn into wine. For me it became a kind of retreat into the company of people from all over the world.

All photos in the publication: Albert Lores

Photographer from Madrid. For the last six years, he has been working in wineries in Europe, America, and New Zealand to earn money for traveling and creating photo projects. Now he lives in Ukraine, and works on stories about Eastern Europe and Northern India.

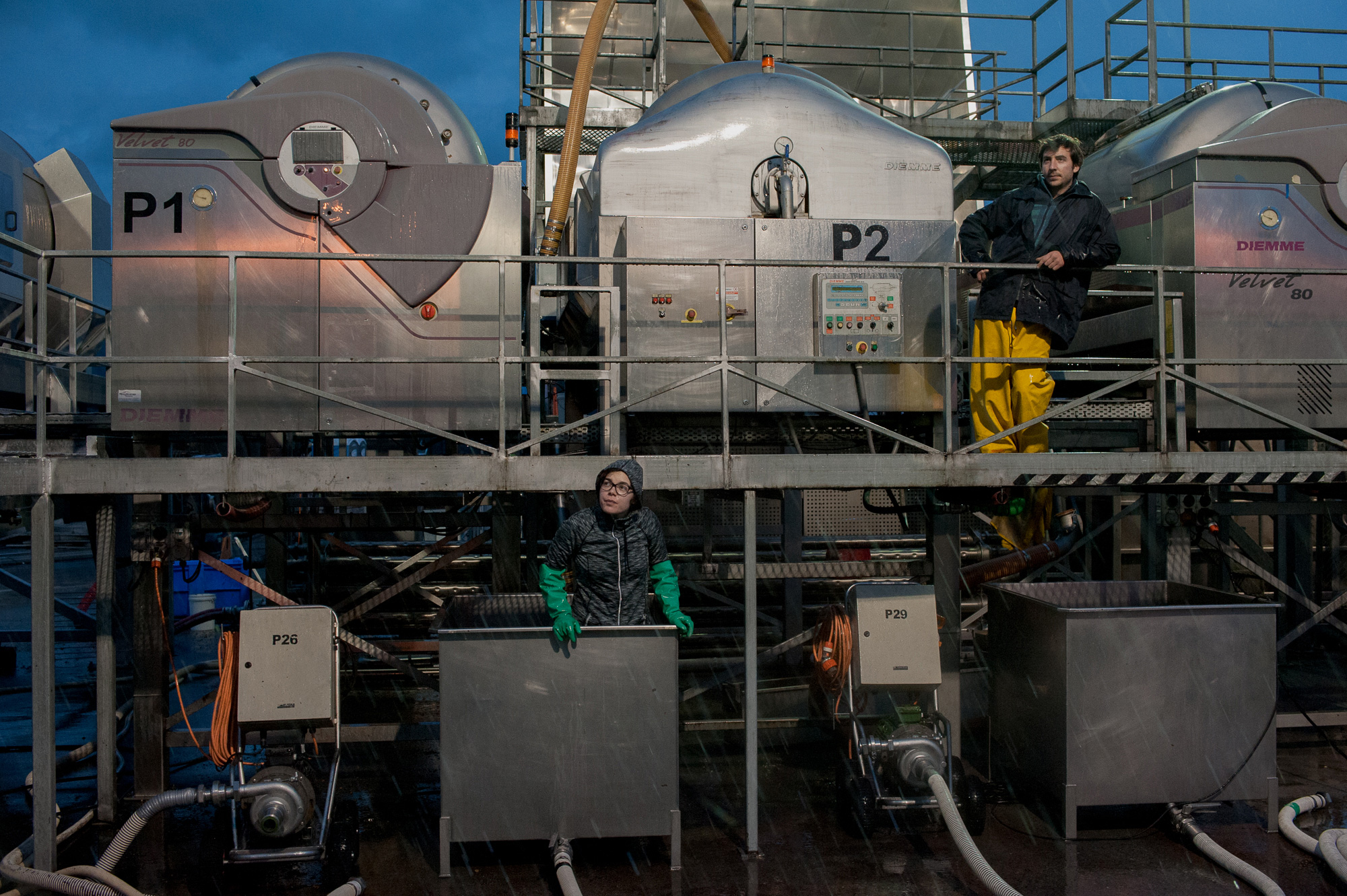

Maro, winemaker from Greece and Pierre, vigneron from Bordeaux near the presses area.

Lunch break at two o'clock in the morning. Instant coffee and pizza

The winery reminds me not of a monster but of a spaceship with a manual transmission. Here one must not to be afraid of heights, darkness, chemicals, confined spaces and monotonous physical work. It is necessary to react quickly, calculate precisely, and to fight for rubber seals to connect hoses to pumps and fittings which are never in place.

Grape skins after pressing.

We are divided into several teams: Presses, Whites, Reds, Fermentation, Laboratory, Filtration, and a “Sugar Team.”

In fact, almost everyone does almost everything. A Californian chef helps two Kiwis to move a four-inch hose full of juice and connect it to the tank; a French teacher and theater director curtseys to the driver of a truck full of grapes when he has to stop at the hopper’s edge. Her boyfriend, in a panic, is looking for a spanner to tighten a juice-leaking valve. A fragile dancer from Britain stirs hundreds of sugar bags, handed over from the complaining heir of a French chateau. In New Zealand it is legal to add sugar, in fact it’s widely used when the fruit is not ripe enough.

Among my colleagues are French winemakers, graduates from the University of Bordeaux; a forty-year-old Chinese man abroad for the first time,; the owner of a wine cellar from Portugal; winemakers from Argentina, Greece, Italy, Mexico, and the US; a British woman who just graduated from school; an Argentinian girl with a marketing background; two veterinarians from Chile, in a sabbatical year traveling around the world; and a former construction company manager from Spain, who seven years ago, exchanged ‘business life’ for traveling.

Some can precisely tell the acidity level of a fermented juice just by tasting it and spend half their salary on rare wines; others prefer a cold beer for dinner.

The winery production is outdoors, when it is raining the activity does not stop, we worked in a ‘waterproof banana costume’

Pierre inoculates the yeast and with the help of the pump mixes it inside of the tank to start the fermentation.

Camille, a french theater director, cleans a juice tray from the presses after use.

Sunrise. Maro in a trailer where grape skins will be disposed after pressing.

Most people have time to hang out after work. The bars and cafes are crowded. Winemakers share stories and dance in rubber boots, pour craft beer and ‘mimosa,’ get acquainted and fall in love.

They are eighteen and in their forties, they are monogamous and they enjoy polyamory, they play saxophone and ride horses, they live in a car for months and they buy expensive houses, they vote for the left and for the right, they believe in God, communism and in a world without borders.

Bo and Pierre, before going to the winery to start their shift.

Ines from Portugal

Take over between day and night teams. Tamara from Argentina; Gregor, British; and Matthew from the US.

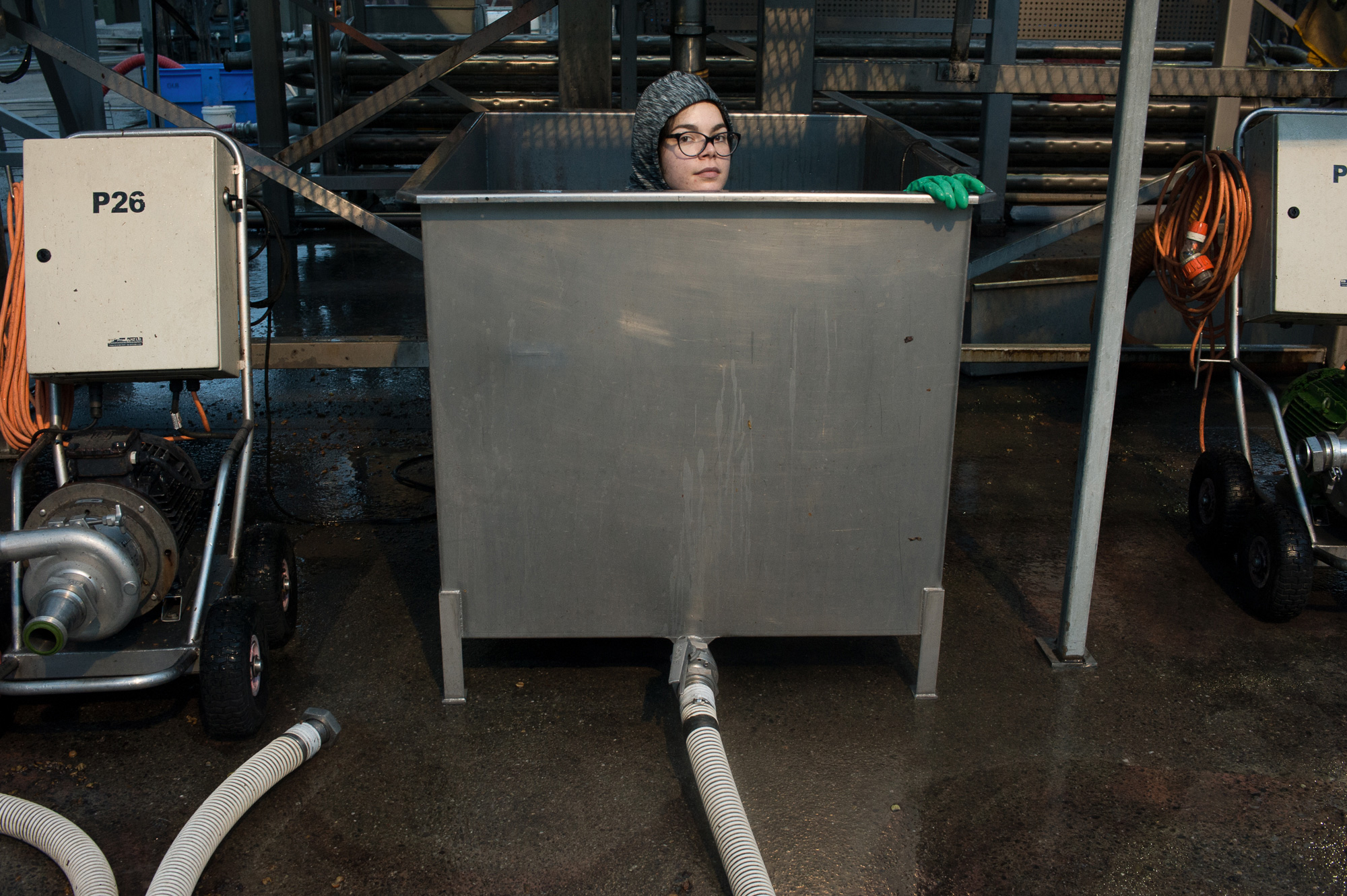

Maro sanitizing a juice bin near the press.

Literally chasing autumn, up to four times in twelve months, not seeing spring for years. In their passports, work visas from Australia, Canada, the States, France, Germany, Switzerland, South Africa, China and tourist ones from all around the world.

My boss was a girl from China. She studied medicine and chemistry, wanted to ‘save lives,’ but later realized that pharmaceutical companies focused on making money, not helping people, which is why she chose winemaking: “At least it makes people happy.”

Daniela from Czech Republic at a climbing gym in Nelson during the weekend.

End-of-the-harvest party at the winery owner's house.