The Divine Spark: Why The Great Chicago Fire Was Actually Good for The City

On the evening of October 8, 1871, the shed of Catherine O’Leary, an Irish immigrant living in Chicago, caught fire. The flames quickly spread to other buildings, starting the Great Chicago Fire. Having raged over two days, it took the lives of three hundred locals and left about 100,000 residents homeless. The city center was consumed by fire. Despite the magnitude of destruction, it took only two decades for Chicago to rebound, becoming one of the USA’s critical transport and trade hubs.

Carl Smith, a professor of history at Northwestern University, explained to Bird in Flight how a regular fire reduced an industrial city to ashes, why it was actually good for Chicago, and what conclusions the architects rebuilding Ukrainian cities could draw from the disaster of 150 years ago.

You wrote five books, all of them about Chicago. What do you find so fascinating about the city?

My interest lies not with Chicago itself but with the US history of the early 19th and 20th centuries. Those were the times that shaped our country into what it is now. Chicago embodies that transformation from an agrarian nation into an industrialized one.

One of your books is about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Why would anyone want to read about a fire from 150 years ago nowadays?

The reasons are multifold. First, it is always impressive when a city is destroyed by fire. Second, we are talking about one of the largest city fires in history. It is comparable to the 1812 Fire of Moscow or the 1666 Great Fire of London, and even those were not as big. Third, it is still a big deal for Chicago residents.

If I remember correctly, a festival was established to celebrate the Great Chicago Fire. That’s unusual, to say the least. Why would one celebrate a disaster?

Because the fire that big didn’t stop the city’s development and even made it the epitome of grit. There is that figure of speech about “rising like a phoenix from the ashes.” Although a tired cliché, this is something you can definitely say about Chicago.

Here is one thing that might surprise you even more than the festival. Two of the four stars on Chicago’s flag, in fact, represent disasters. One is the battle between Native Americans and European settlers in 1812, which the latter lost, and the other is the Great Chicago Fire. It is as if this star sends a message — nothing can stop Chicago.

Two of the stars on Chicago’s flag represent disasters. It is as if they send a message — nothing can stop Chicago.

The flag of Chicago on a building in the city. Photo: Depositphotos

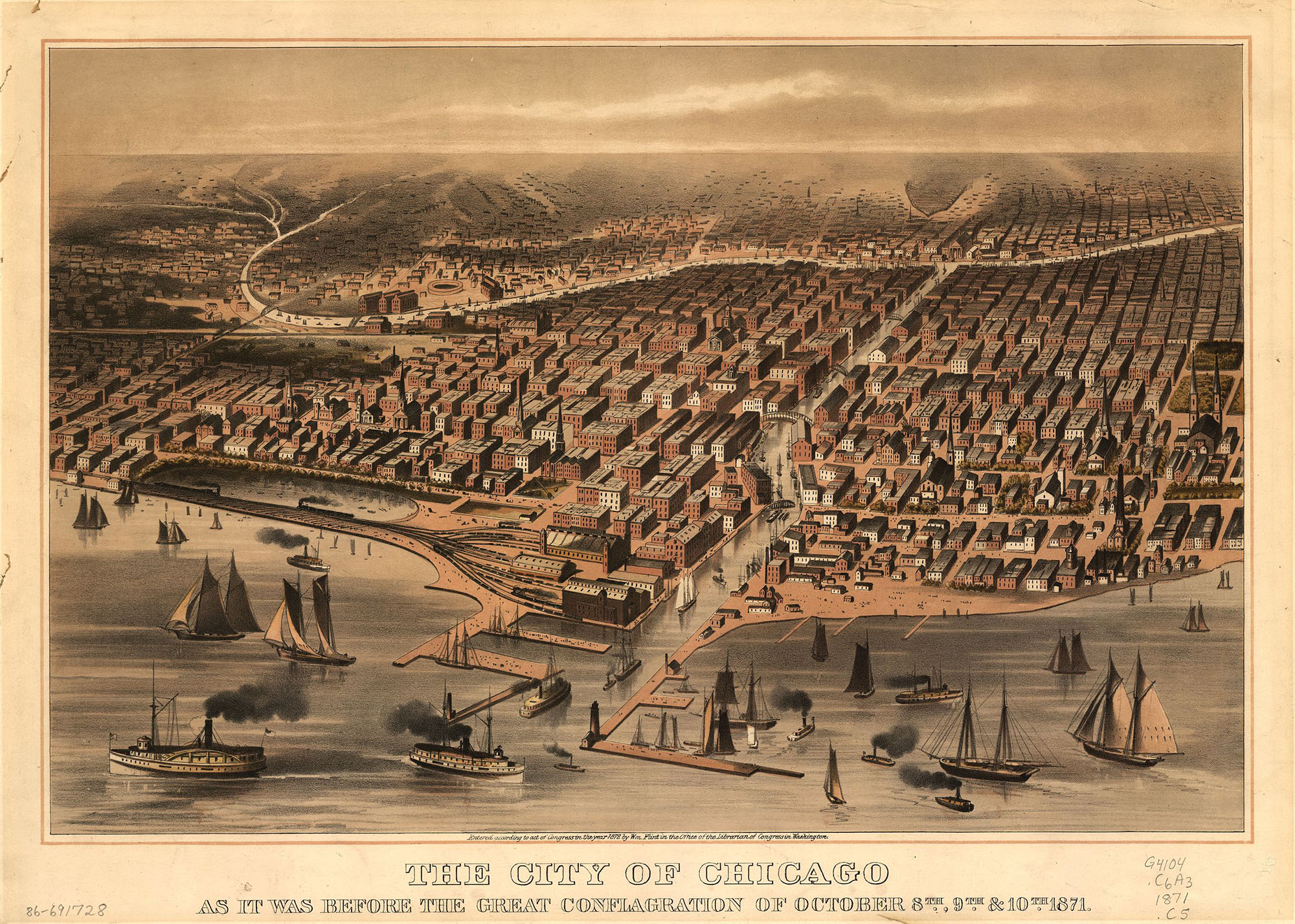

What was Chicago like before the fire?

Chicago is situated between Cincinnati and St. Louis — an excellent location for trade. The city rapidly became the world’s biggest railway hub. By the way, it is home to the largest and busiest railway hub on the planet until now.

The city developed at an amazing pace. Its population was 30,000 in 1850 and reached 300,000 in just twenty years. 75% of people who lived there were migrants. Every fifth was born in Germany, and every seventh — in Ireland. There were also a great many people from Scandinavian countries and England. However, the larger part of the wealth and real estate was in the hands of Yankees — white Protestants from New York and New England, as well as people hailing from the Midwest.

Chicago was divided by ethnicity and religion. One could get citizenship and the right to vote pretty easily at the time, so there were migrants in the City Council, too. There was a lot of infighting. In addition to frequent fires, the city witnessed much social turmoil.

What made Chicago so attractive for migrants?

In 1848, democratic revolutions swept Europe, many of them unsuccessful. People started looking for a better future. Chicago was thriving, so they flocked there. Those who emigrated to Chicago for political reasons were called Forty-Eighters at the time, by the way. And when migrants settle, they pull in other migrants like a magnet, you know.

What was the city like before 1871?

Structurally, it resembled present-day Chicago, with its rectilinear street grid oriented by compass directions. In a typical US fashion, the grid was established in the end-1820s, before the city started growing.

Most buildings were built from cheap pine, the most affordable material at the time. They were rarely four stories high — even the mansions of well-to-do residents had two stories at the most. If you went higher, you had problems with the water supply.

The city had only a few paved streets; the rest were dirt roads with pine board sidewalks. The city center, with opulent houses of the rich, was south of the Chicago River. The poor lived near them but in huts. The city’s industrial plants were situated close by along the river.

Chicago before the fire. Image: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress

Let’s talk about the fire. What caused it?

The story goes that Irish migrant Catherine O’Leary went to her shed to milk her cow. She brought with her a lamp, which the animal knocked over. The shed caught fire, and nearby buildings soon followed.

The fire indeed started in the O’Leary shed (or near it), but the cow was added by the journalists. It doesn’t matter that much, anyway. What’s important is that we understand why the fire did so much damage.

Why did it?

The are several reasons. First, the city had dense wooden development. It made Chicago a very fire-hazardous city in the first place, and the long dry summer of 1871 made things only worse. Second, a strong southwestern wind brought the fire toward the city center — the most populated part of Chicago. The third cause was the big fire that broke out on the previous day’s evening. As a result, much of the firefighting equipment was out of commission, and there was little of it in the first place.

Finally, the firefighters arrived too late. The alarm system — modern for that time — did not work as expected for some reason. It took firefighters half an hour to get to the spot, and the fire had been raging out of control by then.

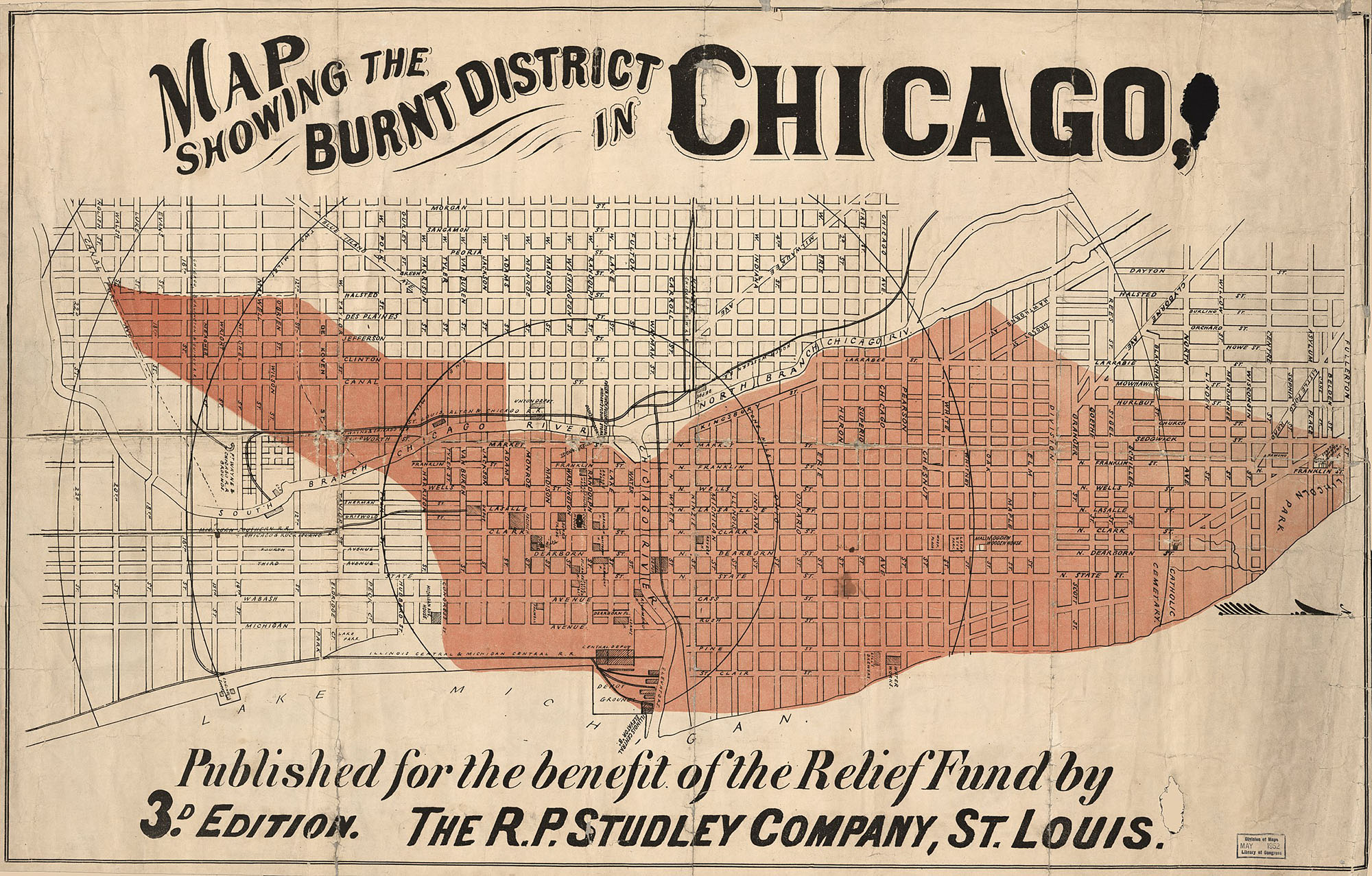

What was the extent of the destruction?

It was enormous. The most valuable properties burned down, taking with them about three square miles (8 square kilometers — Editor’s Note) of the city. A third of the residents were left homeless, and there was no money to deal with the problem quickly. So, the authorities offered a free railroad ticket to everyone who decided to leave the city, regardless of the destination.

Besides, the disaster exposed and deepened class inequality. Wealthy Chicago residents suffered less than poor ones, as they had access to insurance and bank loans. Besides, they owned a lot of real estate, some of which could remain untouched by the fire.

Chicago’s residents flee from the fire across the Randolph Street Bridge. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Chicago after the fire. Image: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress

The aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire as seen from a Randolph Street building/ Photo: Wikimedia Commons / NBY

Did authorities have the plan to rebuild the city?

There was no such thing as “city planning” until the early 20th century. So there was no plan, basically.

In 1871, local authorities were not that powerful, so it was local industrialists and private property owners who handled the rebuilding.

Do you mean there was no centralized body to handle the reconstruction?

There was none. However, there were people who took control of the money raised for rebuilding.

You see, Chicago was long in the spotlight by that point. While the city was burning, all newspapers ran front-page stories about the conflagration. The money for rebuilding the city came from all over the world, totaling $10 million in today’s money.

After the fire, the city elite persuaded the mayor to let them handle the money, reluctant to entrust it to the City Council, which was composed of immigrants for the most part. The money was spent on hiring workers to rebuild Chicago.

Who were the people in control of the money?

Those were members of a small private organization founded by the city’s richest — The Chicago Relief and Aid Society. Its most influential member was lawyer Wirt Dexter. The Society also included George Pullman, who earned its fortune from building rail cars, and the city’s richest man Marshall Field, who made department stores as we know them.

Before the fire, the Society helped people who had trouble with money because of illness or age (the so-called “deserving poor”).

Did they succeed in rebuilding Chicago without a plan?

They could have done a better job, naturally, but they did it. Their success was primarily due to Chicago being too important for the country. The fire destroyed buildings, but telegraph lines, railways (except for those in the city center), and the port survived. I can go so far as to say the fire spurred the city’s development, helping it get rid of the “bad” buildings.

The fire spurred the city’s development, helping it get rid of the “bad” buildings.

Local authorities were weak and had little say in the process. All they did was raise fire safety requirements, primarily by expanding the zone for the construction of buildings exclusively from brick and other fire-proof materials. In fact, this decision resulted in a riot at a City Council session because brick was prohibitively expensive as a construction material. As a result, the new requirements did not come into force until the early 20th century.

What did that riot achieve?

In brief, it was in vain. Elites despised immigrants, especially the Irish, but still needed them to remove rubble from the city center and work at the plants. Despite the importance of migrants for the city, elites did everything to keep them in check and away from the City Council.

The map indicating the burned-down territories. Image: Wikimedia Commons

How long did it take to rebuild the city?

It was extraordinarily quick. Merely in two years, the city center doubled in size as compared to its pre-fire size, and the population increased, too.

How much did the reconstruction cost?

It is easier to calculate the damage caused by the fire, which amounted to $200 million or about $5 billion in today’s money.

How did Chicago change post-reconstruction?

The expulsion of workers and the poor from the city center gathered pace. As people left, churches followed. The city center became a commercial zone.

The resettlement boosted tram and shuttle train development, turning Chicago from a pedestrian city to a railway one.

Did the city center benefit from that?

Well, it became more utilitarian than beautiful. No public spaces, no quaint streets.

I heard that one of the city’s most beautiful places, the lakefront, emerged because of the Great Chicago Fire. Is that true?

Not exactly.

Before the fire, there was a lagoon across the city center. When the flames were put out and people started clearing the debris, there was so much of it that the decision was made to dump it near the water. Those dumps became the foundation for the present-day Grant and Millennium parks. However, the work on the parks began way before the conflagration. The thing is that the lake is essentially the city’s only natural site, so the authorities could not afford to damage it. Even now, Chicago’s lakefront is green and undeveloped.

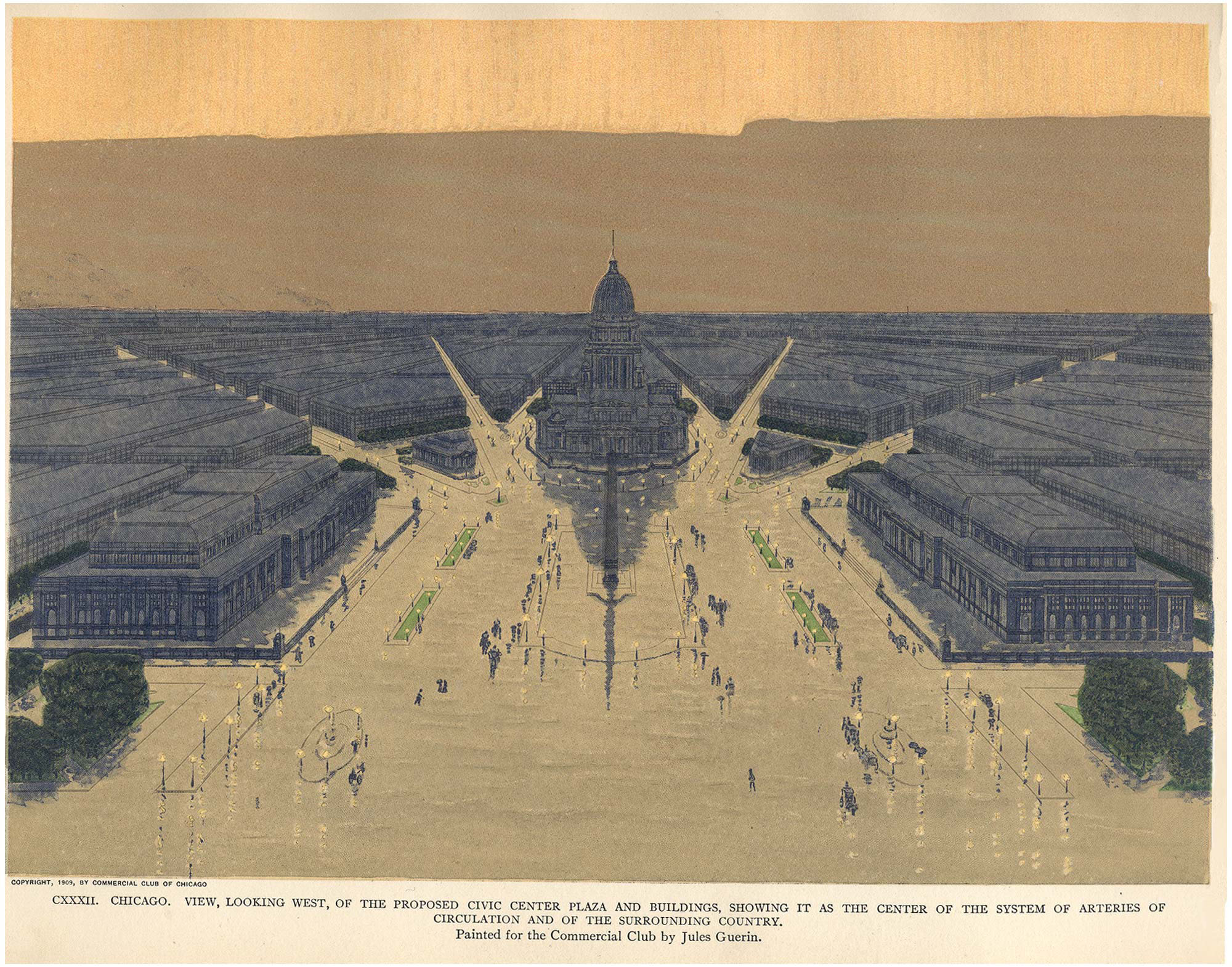

Sounds like the city changed after the fire, but not that much. When did it become the USA’s architectural capital?

It all began with the 1893 Columbian Exhibition, which Chicago happened to host. Daniel Burnham designed terrific buildings in the Beaux-Arts style for the fair, and people started wondering why couldn’t their entire city look like that. A reinvention of that kind was characteristic of that time. In the 19th century, European cities became more beautiful, too, and the USA saw the rise of the City Beautiful movement, which aimed to beautify American cities.

Burnham was also preoccupied with the fact that wealthy Americans made money in Chicago and spent it in Paris or Venice. He was passionate about making Chicago as gorgeous as Paris.

Burnham was passionate about making Chicago as gorgeous as Paris.

In 1909, Burnham developed his plan for rebuilding Chicago. The plan was nothing original: the author just compiled the ideas that existed before him into one document. The architect insisted the lakefront belonged to the people, proposed to build a regional highway system and railway stations, and offered to set up cultural centers, plant greenery, widen the existing streets, and construct new, diagonal ones. Burnham was a good promoter and PR specialist—and it is essential to know how to sell your ideas in the USA—so his plan was implemented, albeit only partially.

The 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Grand Arch of the Peristyle, Chicago, during the 1893 Columbian Exhibition. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A fragment of the Burnham Plan. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In your opinion, would Chicago have become an architectural center if not for the fire?

I believe it would have.

People went to Chicago not because of the reconstruction but because of the financial collapse that shook the country two years after the fire. It was one of the most hard-hitting depressions in US history.

It was then, in 1873, that Louis Sullivan — one of Chicago’s most famed architects and the “father of skyscrapers” — arrived in the city. A young and promising architect educated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he immediately realized that Chicago was the city of opportunity. Sullivan worked for William Le Baron Jenney, the engineer often credited with erecting the first steel frame building. The steel frame developed by Jenney carried the structure’s weight instead of the walls, enabling the construction of taller buildings.

The 20th century brought a lot of construction initiatives. Did they try to change some of the city’s flaws?

The city was too big to reach a consensus regarding its general plan after implementing the Burnham Plan, so most initiatives were confined to city districts.

Now we have the big Chicago 2050 plan. It’s much more practical than Burnham’s ideas.

Present-day Chicago. Photo: Depositphotos

Why doesn’t Chicago appear in the lists like “The USA’s best cities to live in” nowadays?

Not to defend or advertise Chicago here, but I’d like to say I have always been skeptical about such ratings.

San Francisco used to be the top city, but then it lost its appeal because of its homelessness problem (which was blown out of proportion, in all fairness). Chicago has had a reputation as a city with a horrible climate, which does not reflect the actual situation if you consider the accurate figures.

What conclusions can the architects rebuilding the Ukrainian cities draw from the history of Chicago?

I study the past, but if I can tell you one thing about the future, it is that the world is changing, and you would be better off constructing cities independent of Russian oil and gas. Go with green energy, better transport, and the like. Play it long and consider what people would need in 50 years.

Looking back at the Great Chicago Fire, the most important lesson to be learned is that places do come back.

Cover image: Depositphotos, Wikimedia Commons

New and best