Please, Don’t Stop: How Berlin Started the Reconstruction and Has Never Finished

After World War II, USSR and Allied representatives in Berlin had to tackle two problems at the same time: to restore the city ravaged by hostilities and rid it of the Nazi architecture. The sheer magnitude of destruction and lack of architects, most of whom perished in the war, created a critical situation, and the division of the German capital into East and West Berlin was the final nail in the coffin of the city’s post-war architectural consistency. However, the city ultimately rose from the ashes and even became Europe’s architectural and cultural powerhouse.

Architectural and art historian Andreas Butter has been studying transformations in Germany’s most important city since he visited East Berlin in the 1980s. He told Bird in Flight how Berlin rebounded from World War II ruin, dealt with Nazi architecture, and used the competition of the Socialist and Capitalist systems to its advantage.

What was Berlin like when Hitler came to power?

Berlin became a metropolitan city in the 1870s. It had housing and industrial areas as well as its historic centre with broad boulevards and government buildings. The central part of the city was surrounded by densely populated houses of the end-19th–early 20th century. They had elongated courtyards filled with shacks, where people held all kinds of things, including cattle. In the 1920s, the so-called White City (Weiße Stadt) — a ring of new, modernist buildings — was constructed. Spacious and painted white, those had large windows and a lot of greenery in the courtyards. There were also those districts for the unemployed, where locals were given small plots of land to sustain themselves. Also, Berlin was surrounded by orchards, which turned its outskirts into more of a rural area.

It was a city of economic growth, where people came from all over Germany to work. However, it felt the touch of the 1930s Great Depression, too. In fact, it was when the Nazis came to power.

How did they change the city?

Instead of modernist buildings, they started constructing traditional ones with small square windows. Monumental governmental buildings were put in the centre of the city, like the Ministry of Propaganda, Ministry of Aviation, and Reich Chancellery.

At the end of the 1930s, a major reconstruction of central Berlin was launched. The authorities built wide avenues and domed marble palaces with statues. The Nazis had to tear down a lot of older development to implement this project. The people who lived there settled in the flats of the Jews deported to the ghetto. The Nazis’ construction guidelines were the extension of their military and antisemitic policies.

Berlin reconstruction model based on Albert Speer’s plans; the view of Triumphal Arch. In the back is the Volkshalle, with its dome 250 metres in diameter. Photo: Bundesarchiv / Wikimedia Commons

Which of the plans were not implemented?

The Volkshalle with its dome, which should have been the largest in the world, was never built, and the so-called House of Travel, a half-circle building with numerous arches and columns, was only started. Nazis constructed relatively few buildings, but their architectural heritage is apparent in Berlin, with the buildings of the Ministry of Aviation, Ministry of Propaganda, and the Ministry of Justice, to name a few. Some of them underwent restoration in the 2000s.

Why weren’t all those torn down after the war?

Unlike much of Berlin’s other development, the steel-and-concrete architecture survived the war. And then it was preserved because the city had to function. The edifices too closely associated with Hitler, like Reich Chancellery, had to go, though.

The building of the former Ministry of Aviation that now houses Germany’s Ministry of Finance. Photo: A. Savin / Wikimedia Commons

The Banana Bunker. The owner’s penthouse was added on the top floor after the Reunification of Germany. Photo: Flocci Nivis / Wikimedia Commons

Did the Nazis build anything else during the war?

They built bunkers. One enormous specimen is still intact at Albrechtstrasse — it currently accommodates an art gallery. The Soviets used it as a prison at first and later converted it into a banana warehouse, hence the name — the Banana Bunker.

There were even 30-metre-high bunker towers with rounded corners and flak cannons on the top. Those were too massive to demolish, so they were covered with rubble from the destroyed buildings. Now, they look like regular hills — there are a few of these in Berlin. It was done to demilitarize Germany.

How was Berlin destroyed?

At first, by Allied bombing. Then, the Nazis started blowing up ammunition warehouses and bridges to stave off the Allied offensive. When Polish and Soviet troops attacked and encircled the city during the Battle of Berlin, they severely damaged its eastern districts by shelling. The final wave of ruination happened during the post-war decline.

What was the magnitude of destruction?

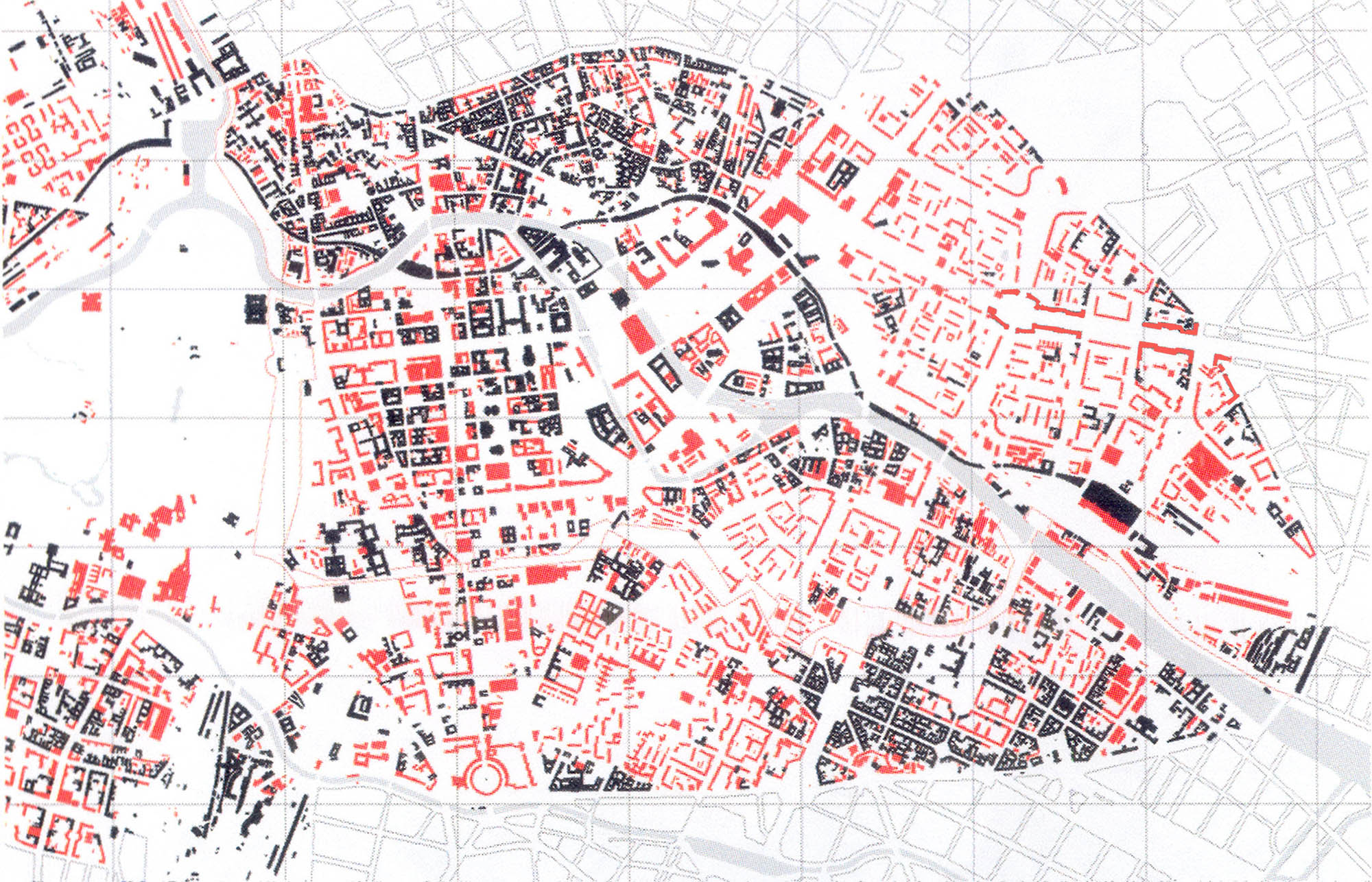

Every building in Berlin was damaged in one way or another. The city lost around 300,000 houses. Only 29 out of its 234 hospitals survived. In Mitte and Kreuzberg, the city’s central districts, up to 90% of the development was wiped out. However, the further you went from there, the less destruction there was. In the outskirts, hardly 10% of the buildings were destroyed.

The view of Berlin Cathedral in 1945. Photo: Berlinische Galerie

A temporary bridge over the Spree River in 1945. Photo: Berlinische Galerie

After the war, Berlin was divided between four Allies. What was the rationale behind it?

De jure, the city was divided into four parts, but in fact, there were only two: East and West Berlin. The borders between the three West Berlin zones were unnoticeable, with only cultural and military institutions indicating the side to which each belonged. In their zone, the Americans built the American House and opened a New Anglican Church where the Federal Archive of SS used to be: the building looked like a church built somewhere in Massachusetts. But it was rather an exception. The British did not add any ‘cultural markers’ in the city.

For the sake of convenience, Berlin was divided along the railways. I remember taking a train when I visited Berlin in 1986. It departed from the GDR territory and then passed between the Berlin Wall’s barriers. Stopping there was prohibited, and police kept an eye out for the passengers trying to escape to the other part of the city through a carriage window. Locals dubbed that part of the way ‘the death strip’.

In other places, the border was not tied to geography in any way. The Potsdamer Platz, which had no railway facilities whatsoever, was divided by a demarcation line.

Some people wrongly believe the Berlin Wall was erected in the 1940s. However, it was built only in 1961, and the city’s division and reconstruction started way before that. By the end of the 1940s, Berlin was governed from a united centre despite being occupied by multiple forces.

What problems did the post-war reconstruction of Berlin encounter?

Rebuilding was hard. Many specialists that would have been invaluable for this cause either perished in hostilities or ended up in Soviet prisons. Berliners were depressed after the shock of defeat in World War II.

The Allies returned the city to peaceful life, albeit arrests, burglaries, and rape persisted.

The Allies returned the city to peaceful life, albeit arrests, burglaries, and rape persisted.

There was no gas, steel, or coal. Soviet troops were dismantling railways and factory equipment and sending it all to the USSR. The economic situation was difficult, too.

In its early stages, the restoration focused on the most pressing problems, rebuilding hospitals and establishing humanitarian aid stations at schools. Having won the 1946 elections, Social Democrats started working on the plans to rebuild Berlin. However, the Soviet Union started blocking the western part of the city, dividing Berlin into two blocks.

The remaining span of the Berlin Wall. The Berlin Television Tower is seen in the back. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How was East Berlin rebuilt?

The Communist authorities relied on modernist restoration principles before 1950 but then changed their approach.

German architects went to Moscow to meet with their Soviet colleagues and politicians and then came up with the National Traditions Doctrine that involved the construction of the Communist Party buildings and sprawling squares. That approach heralded the arrival of the Stalinist period in East German architecture.

Soviet authorities preserved old housing and renovated the 19th-century buildings but destroyed the Berlin Palace while cleaning up the squares for parades.

In 1954, Khrushchev delivered his speech ‘On Useless Things in Architecture’, giving rise to a more functional architecture and, subsequently, the panel housing. Before that, most architects were partisan to the American architectural approaches and reluctant to switch to traditionalism. Many of them started out in West Berlin back when the border was still open.

How did the Berlin Wall affect the development of the city’s eastern part?

When the Wall appeared, the restoration of Berlin became the competition of two systems.

Before that, the two parts of Berlin were a showcase: the Stalin Alley in East Berlin and Hansafiertel in its western part were open to all residents. The Wall gradually made those kinds of visits impossible, especially for East Berliners.

A show-off race began on both sides of the Wall. In West Berlin, the gilded Axel Springer Hochhaus was built, which came to embody the image of the ‘golden West’ and freedom of the press. The Soviets built a few high-rises on their side of Berlin, too. Housing industrialization in the eastern part of the city meant stabilization of the economy.

The Berlin Wall turned the restoration of the city into a competition.

In the 1970s, however, it became apparent that older buildings were crumbling down, and the new development couldn’t keep up to satisfy Berliners’ needs. The Communist authorities made a vain effort to tackle the problem by revving up the construction of faceless prefab housing up until the collapse of the GDR. This is why late-GDR accommodations were so dull that residents despised them.

A house designed by Walter Gropius in the Hansaviertel district of Berlin. Photo: Gunnar Klack / Wikimedia Commons

The view of Karl Marx Alley (formerly Stalin Alley) from the television tower in 1970. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Axel Springer Hochhaus. The golden part was built in the 1960s, and the glass one in the 1990s. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What was the restoration of West Berlin like?

Local architects had more freedom, so the architecture of West Berlin was replete with detail and mosaics, especially in the 1960s.

The West wanted to showcase the manifestations of the economic miracle that finally happened in 1953. The buildings were more humane than in East Berlin. They were positioned to catch more sun and had balconies. Also, office buildings, shops, and cinemas were built in the western part of the city. East Berliners considered West Berlin the consumerism heaven.

How was the housing shortage tackled there?

West Berliners had a higher income.

Some parts of the city were declining, but things generally went better than in East Berlin. In the 1960s, West Berlin authorities started tearing down buildings in the centre of the city, moving people from there to the housing in the outskirts.

What did they build in West Berlin?

Hansaviertel, a residential district with blocks of flats designed by prominent modernist architects such as Gropius, Niemeyer, and Aalto, is the first thing that comes to mind.

Restoration of older residential quarters and construction of post-modern-style housing began in the 1980s. In the latter case, houses often had small windows and looked funny in general.

What kind of challenges did the city face after the fall of the Berlin Wall?

The challenges were many: redundant state agencies, privatization of real estate, the need to tear down the Wall, which was basically a mined zone, and, finally, the exodus of East Berlin residents.

One of your books is called Die Mauer als Ressource (Wall as a Resource). Apparently, the Berlin Wall brought not only bad things but good ones, too. What were those?

For one, those were the numerous options for developing the empty space where the Wall used to be. The first one was a Cold War monument and an art gallery; the second was parks and greenery; the third was cultural facilities; and the fourth was commerce. In fact, all of those were implemented one way or another.

Some believe the Wall made Berlin the city of the unique culture we have come to appreciate so much. Do you agree?

Every generation of Berliners thinks of themselves as underground and rebellious. Berlin’s unique culture is a myth, too, in my view. Frankly, this culture lacks new and crazy things. Still, people flock to Berlin to enjoy it.

Berlin’s unique culture is a myth, and the Berlin Wall helped establish it.

The Berlin Wall indeed made a fertile ground for the myths about the city’s culture. In the times of the Berlin Wall, there were two counterculture hubs in the city: West Berlin’s Kreuzberg and East Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg. In the eastern part of the city, counterculture brewed in flats and courtyards. After the Wall fell, desolate industrial buildings and their basements turned into techno bars and venues for parties, which were often kept secret, with admission through a hole in the fence.

What did the authorities of Reunified Berlin do with the Socialist-era buildings?

Their hate toward the Soviet style resulted in the destruction of many excellent specimens of the GDR architecture. They left the Soviet housing, and the Republican Palace was dismantled.

However, then the leftists came to power. They made every effort to preserve whatever heritage there was. They were the ones who insisted on keeping the Haus der Statistik and Berlin Television Tower. Residential areas with kindergartens and shops were preserved and later restored, too.

Is it worth reconstructing the already destroyed buildings?

It’s a tricky question, and I have mixed feelings about that. I am a preservationist, and I believe it’s essential to preserve what’s still there and focus on those things that decline. Only then it makes sense to restore what has been lost.

As I see it, the materials bear the aura of their time. You need to think twice before demolishing a top-class 1950s building to restore something no currently living human being has seen before. Why would you sacrifice one piece of history to artificially rebuild another?

But there are more recent views, too. Like, if people want to restore something, and we are talking about democracy, it needs to be done. Alternatively, something can be necessary for the environment and thus highly desirable to reconstruct, especially if the builders have access to original materials.

The Berlin Palace reconstruction was completed late last year, hence the question: does restoration of Berlin continue still?

It does. In 1910, Karl Scheffler wrote that Berlin is condemned to perpetually become but never be. He was so right. Other cities are different in this regard. Paris is Paris, while Berlin is a never-ending change. There are still problems with establishing ownership of some buildings; some houses are deserted; and there are burnt façades and desolate industrial zones. Still, the city keeps developing.

Berlin is condemned to perpetually become but never be. Berlin is a never-ending change.

During the restoration of Dresden, local authorities refused to invite the Jews back to the city, creating a bunch of problems for residents and tourists. What did Berlin do for the return of the Jewish community?

Well, I guess we should ask people from the community about that, but I think the city did a lot. It rebuilt synagogues and constructed the Holocaust Memorial and the Jewish Museum. Private institutions committed to creating the so-called ‘stumbling stones’ that bear the names of the Jews who lived at those addresses before the war.

Still, it’s dangerous to wear a kippah in some places, and Jewish establishments often have armed guards. Older people sticking to Nazi views, those with leftist anti-Israel attitudes, and immigrants from Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries hate Jews. However, antisemitism is not that big of a problem among the Germans as compared to noticeable pro-Russian sentiment.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe against the backdrop of Berlin’s contemporary architecture. Photo: Depositphotos

What are the positive traits of present-day Berlin due to its reconstruction?

Well, the city benefited a lot from the competition between the two systems.

A lot of housing was built because of it, as well as iconic buildings such as the Berlin Television Tower and Bikinihaus. It took much effort and money to revitalize the city after the war. Berlin was rebuilt relatively quickly, not over the span of multiple generations.

Berlin had a lot of greenery even before the war, and it became even greener after the Wall fell — as I’ve already said, the Berlin Wall was replaced by parks.

Outside of the commitment to historical styles while restoring the city, approaches to its further development still differ. It’s this persistent struggle between different visions that makes the city so exciting. Instead of one city centre, Berlin has one in every district. It’s another advantage that Berlin has over other cities. It was like that even before the war, but the division of the city helped preserve this multicentricity.

What drawbacks did the reconstruction of Berlin have?

I am an art historian, and I feel it’s essential to preserve the city for future generations. Many houses, churches, and palaces were destroyed after the war. And that process continues to this day. Sixteen years ago, the Republican Palace was dismantled to rebuild the Berlin Palace demolished in the 1950s.

Another problem is the enormous housing demand. As I have already mentioned, the eastern part of the city was short of housing, and whatever they built to offset it was of low quality. Now local authorities have delegated this issue to commercial investors, but the housing they build is not that affordable. Meanwhile, stringent German building standards make it impossible to cut housing prices.

The Republican Palace in the early 1990s. It was the seat of the GDR parliament and a venue for various cultural events. In 2008, the palace was dismantled. Photo: Dietmar Rabich / Wikimedia Commons

The Berlin Palace. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Looks like the problems are relatively few. Can Berlin thus be called a thriving city?

You can say that. The problem is that Berlin doesn’t even try to tackle its own issues. Schools beg to be repaired. Also, city authorities prefer to ignore conflicts between the people from various cultures who come here. The residents who can’t pay rent are kicked out of the city centre. Local bureaucracy is sluggish and terrible.

What bits of Berlin’s experience could be helpful for rebuilding Ukraine?

Don’t put off the restoration. If you can rebuild something now, do it. The reconstruction of other things needs to be planned, too. Looking at the pictures of Mariupol, I feel it needs to be rebuilt from the ground up, and you need to start thinking about it today.

Like post-war Germany, Ukraine has a lot of displaced people from the Russian-occupied territories. Think about their needs now, even before the hostilities cease.

I’d also suggest polling Ukrainians, keeping them informed about the restoration’s progress, encouraging criticism, and taking it into consideration. Build high-quality cities for everybody. Entrepreneurial interests may become a powerful motivator, but don’t make everything about making a profit. Negotiate with investors to preserve the historic spirit of your cities. I saw the unfortunately destroyed Sikorskyi building in Kyiv — these kinds of edifices need to be restored no matter what.

Cover photo: Wickman / DPA / AFP, Wikimedia Commons

New and best