‘Reconstruction of Dresden is Fake’: An Architectural Historian on How Not to Rebuild the Historic City Centres

In February 1945, Allied Air Forces dropped over 4,000 tonnes of explosives on Dresden, killing over 20,000 locals and wiping out the city’s centre entirely.

Dresden was rebuilt twice: immediately after the war and in the early 1990s. After the first reconstruction, the city lost its historic buildings for good, turning into a model socialist metropolis — rational, albeit empty. The second reconstruction tried to fix the things socialism got wrong. Still, it couldn’t tackle the main problem — attracting residents back to the city.

Mark Jarzombek, an architectural historian and MIT professor, told Bird in Flight why Dresden city centre looks like nothing but decoration despite all the money poured into restoring it after the war.

You have written books on global architectural history as well as on narrow topics, like the destruction and restoration of Dresden. Why have you chosen this city?

Essentially, because I got funding to do that. So, I apologize that it wasn’t a big intellectual decision. The Minister-President of Saxony, basically, happened to be in Boston. And he said he needed scholars to do an urban design study in Dresden. I know German, so I said I could join that team.

Working in Dresden, I realized that most books about its reconstruction were written by the PR people, and those wrote only about the good things. I wanted to write a more poignant understanding of how Dresden‘s rebuilding took place.

The traumatic residue of destruction cannot be erased by rebuilding a city. So, how does one incorporate rebuilding a city and respecting the underlying traumatic events? That was the fundamental question I was trying to ask.

Before we discuss the reconstruction, can you please describe Dresden before World War II? What did it look like?

Up until the bombing of 1945, the city had had no damage to it at all, mainly because the Germans and Allies both assumed it had minimal military importance despite having railways, train yards, and all.

Dresden was a gem — one of the most prominent European Baroque landmarks full of palaces and churches dating back to the 17th–19th centuries. It was Germany’s cultural capital steeped in history — ‘Florence on the Elbe’, as the Germans used to call it. The country’s intellectuals lived there. Everybody was sure that Dresden won’t come under bombing.

Why did the Allies bomb it anyway?

The Allies reckoned destroying railways would help the Soviet troops occupy Eastern Germany. The Russians said the Allies bombed Dresden because they were evil capitalists.

Why did they really do it, though? No doubt, they bombed the city to kill civilians.

But why bomb the historic city centre that didn’t have any railways?

The Allied military believed it was the only way to make Nazis surrender. The bombers that came from England were told basically to get rid of the city. They used firebombs that set ablaze a couple hundred buildings at once. And the fire melted everything, even stone. It sucked so much oxygen that even if you weren’t hit by a bomb, you died of asphyxiation. There was no oxygen left in the city because the fires were consuming it.

The Allegory of Goodness statue looks over the ruins of Dresden city centre. View from the Dresden City Hall. Photo: Deutsche Fotothek / Wikimedia Commons

As far as I understand, the restoration didn’t begin until the 1950s. What took it so long?

You’ve got to get rid of the rubble first. Now, we have much better equipment for that. While the men went to work at the factories, women formed those long chains, picking up bricks and taking them away to some dump. And those mountains of rubble have forever changed the urban landscape. Some remain in Dresden to this day.

Architecture is a slow process. You’ve got to manufacture lightbulbs, concrete elements — everything. It takes time to do all that, and find money, too. It’s always the problem with the rebuilding — the time lag.

I read in your book that the ruins were dismantled long into 1962, and there was a shortage of people to do that. In Warsaw, for example, locals were eager to dismantle the old stuff to rebuild the city. Why weren’t the Dresdeners interested that much?

Warsaw was sort of an anomaly in that they basically decided to rebuild the city as it was before. Dresden was the opposite — the Socialists said it was a ‘tabula rasa‘, a clean slate. They decided to build what we would call a modern city with nice long and straight streets.

The locals weren’t really involved in any of that. They had no say in what their city would look like.

Where did the people live after the war ended?

The Socialists launched the Plattenbau housing projects, under which they built those apartment blocks you see all over Eastern Europe: long, tall, five to six stories high, and with no elevators. And then there were factories nearby where the people would work.

At first, it was ambitious. They had beautiful plans, and then it became cheaper and cheaper for lack of resources.

Women and youth removing rubble in August 1946. Photo: DPA / AFP

Sheep grazing around the ruins of Dresden Frauenkirche on the 13th of September 1957. Photo: Slub Dresden / Deutsche Fotothek / AFP

Regarding this big plan, I heard there was a competition. Who made the winning plan, and what was it about?

The competition was held in 1946, and the winner was German architect Herbert Konert. The winning plan was a compromise between history and modernity. However, none of it really came to fruition.

They held a competition just to celebrate and say, hey, we have a plan.

What plan did they use to rebuild the city?

The plan was radical and quite simplistic — it was drafted under the guidance of Dresden mayor Walter Weidauer.

In the center of the city, they wanted to build Kulturpalast — the culture palace with an assembly hall where the Socialist party could host its large meetings. And then they had those wide, straight streets and the housing. The housing blocks sometimes had a linear or zigzag shape. Then just make an industrial zone and pop in a couple of schools, and you’re basically done. After the war, you didn’t have time for complicated urban thinking. You just had to build what you thought you needed.

What did they do with the old buildings during the GDR period?

Some were demolished, and others remained but were not reconstructed. Socialists were thankful for the destruction of churches and palaces and didn’t plan to rebuild them. The new regime wanted to show that Dresden was a place for a new Socialist project.

Socialists were thankful for the destruction of churches and palaces. They wanted to show that Dresden was a place for a new Socialist project.

They left a few buildings up because they didn’t know what to do with them, like the Frauenkirche in the city center. They turned its ruins into a major memorial to Allied atrocities, with a big heap of black, scorched stone.

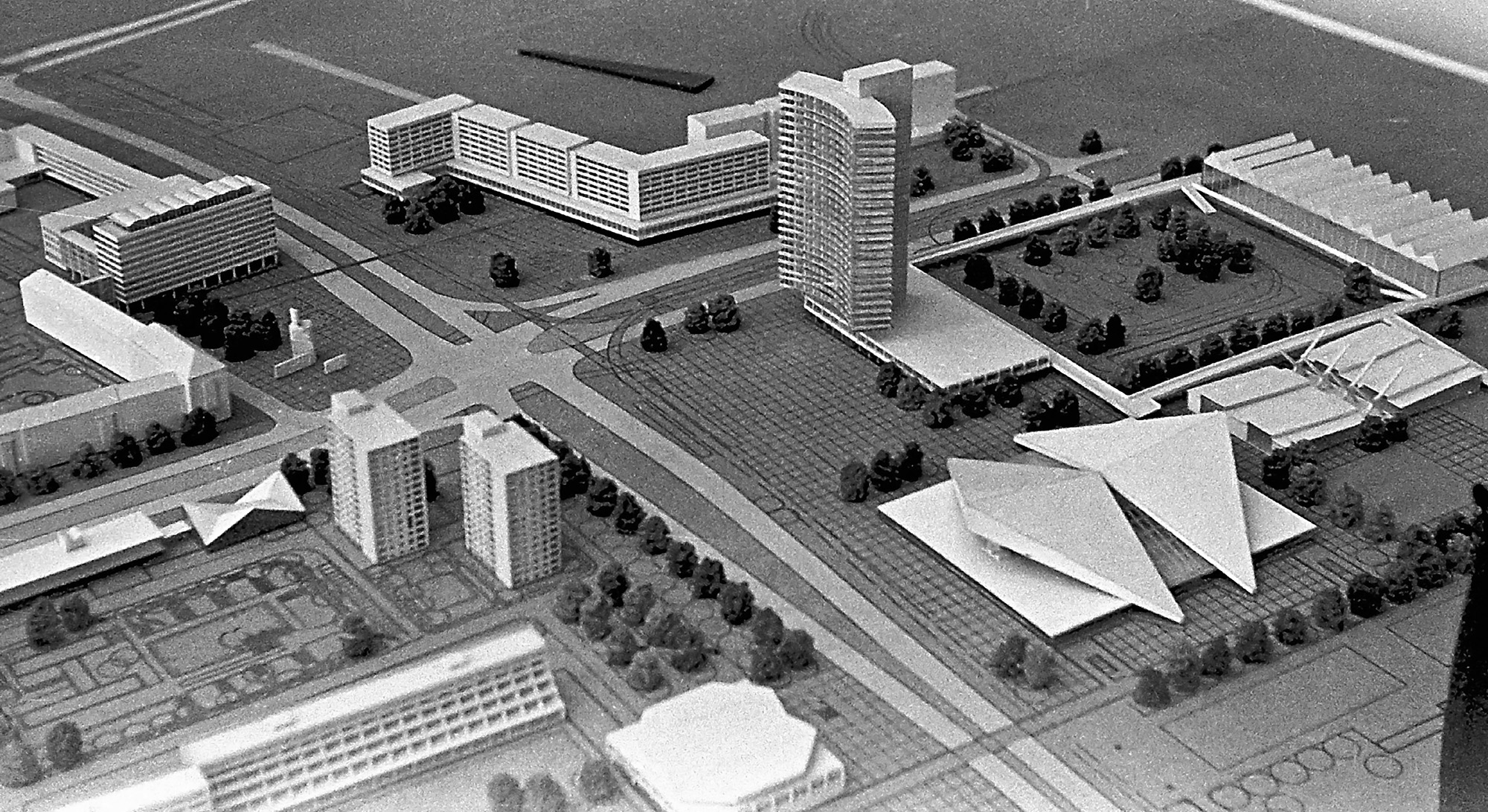

The city centre development plan, 1949. Image: Das Neue Dresden

The Dresden Royal Palace at the beginning of its 1991 reconstruction. Photo: Matthias Hiekel / DPA / AFP

Where did the reconstruction funds come from, and how much did it cost?

It’s hard to say how much it cost because it was never finished.

I don’t know what precisely the funding stream was, but it came from the government. Some of that money might have come from Moscow. In time, however, it became smaller, and, as I said, they had to refuse some plans. They tried to adapt and develop more efficient construction systems, but those meant cheaper buildings that didn’t last as long.

So what Socialists achieved with their reconstruction?

If you were a Socialist, you might say they did a great job. Their ambition was to make it a model Socialist city, and they made it a liveable place, that’s for sure.

The Socialists were great at pragmatism but terrible at outdoor spaces. All those outdoor spaces were basically empty streets: no parks, schools, playgrounds, coffee shops, or bakeries. People had nothing to do there. After work, people would just go home. There was little attention to street life as a way to get a sense that the city is a living thing. One of the first things that happened after the Reunification was that they put a McDonald’s there, and suddenly everyone was outdoors.

People had nothing to do outside. After the Reunification, they opened a McDonald’s at Dresden, and suddenly everyone was outdoors.

The failure wasn’t necessarily that they didn’t do housing right or the People’s Palace was bad. It didn’t make a joyful sense of urbanity. There was nothing of the sort in Dresden.

Model of the Strasbourg Square at the end-1960. The planned exhibition hall at the front with the wing-like two-part roof and the high-rise near it were not constructed. The exhibition hall with a large X-shaped structure erected in 1970 was demolished in 1999. Built in 1968, the two 15-story prefab apartment blocks at Grunaer Straße, 24/26, (on the left) still exist. The 5-story houses with a pitched roof built in 1954–1955 across the street are also still there. Photo: Jörg Blobelt / Wikimedia Commons

The Pirnaischer Platz view from the Dresden city hall, 1972. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Dresden was rebuilt twice: first, after the war, and for the second time — 50 years later in the 1990s and the 2000s. What did the second reconstruction aim to achieve?

When the GDR ended, the authorities decided to eliminate the Socialist heritage. And that was a problem. They didn’t know what to do with the numerous Socialist monuments in the city. Even renaming the streets was difficult — older people still use the old street names.

Another goal was to restore the city’s historic center. It was rebuilt from scratch as it was before the bombing. The ruined Frauenkirche was reconstructed, too.

After the Reunification of Germany, what did they do to the GDR residential neighbourhoods?

The housing was low-quality, but people felt comfortable there and didn’t want to move. Some buildings had to be torn down because they were past their usable lifespan. Others were kept but added an external façade to thicken the buildings, adding a balcony level and generally more space because the apartments were tiny.

The attempts to erase the Socialist past were pretty substantial, and it‘s hard to find physical evidence of it.

If you drove in Dresden today and compared it to what it was in the 1970s, you wouldn’t recognize it. The monuments are all gone, the streets were renamed, and the city center is all Baroque.

Who made the decision to restore the Baroque city center?

It was a political decision made by then-Prime-Minister of Saxony Kurt Bidenkopf. He believed the restoration would attract new people to the city. The authorities ended up pouring billions upon billions of dollars into it.

A panel building at Wilsdruffer Ring, 20, built in the early 1980s. During the reconstruction, the sixth floor was converted into the engineering and utility level, and balconies were added. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Jörg Blobelt

You said only ‘PR materials’ were available when you started working on the Dresden restoration project and that you disagree with what’s written there. What exactly do you disagree with?

After the Reunification of Germany, Dresden was massively underpopulated. The authorities tried to entice the people to return — mostly West Germans, who had money to buy apartments, invest in the technical infrastructure, and so forth. The PR materials made the city look great and wonderful. They advertised great apartments — much cheaper than in West Germany — and the work opportunities at the automobile or other factories that moved there.

One of the issues that came up was the city’s Jewish community.

Why?

Dresden had a vibrant Jewish community before the war. The city used to have a synagogue, but the Nazis tore it down during Kristallnacht. It was rebuilt, but not as it was. If you go to Dresden today, everything is Baroque there; and then you see a strange cube-like modern building — that’s the synagogue.

The problem with that building is that Dresden was famous for its right-wing allegiances in the 1990s (and it is to this day), turning into one of the centers of German Neo-Nazism. And now the synagogue has to be protected 24/7. There are soldiers with big rifles there, and it is tragic. You can go everywhere in the city, and there are only soldiers near the synagogue to protect it from Dresdeners.

That’s a part of the irony of rebuilding. Traumas don’t just disappear because you can make a building again. They continue to cycle in the psycho-social environment for generations until a larger reconciliation is put into play.

Police near the Dresden synagogue after the Yom Kippur shooting of 2019. Photo: Robert Michael / DPA / AFP / Germany OUT

Was this kind of reconciliation found in the Frauenkirche reconstruction?

They attempted to do that.

What the reconstruction of Frauenkirche did was they took the old, burned stones and reused them in the new building. They built a new church that looks exactly like the old one, except for the burned stones on the surface of the building, which are supposed to evoke the memory of the destroyed church.

For me, the problem with this is that they didn’t know where the stones went. They could originally be from any part of the building. So they made a computer program to randomize the stones in the façade. You basically see a building with those black stones everywhere. It gives a false impression of the building as a ruin that was shot at rather than burnt. It’s, like, there’s a bullet hole here and another one there.

I liked the idea of making a building with the scars showing, but the scars, in this case, are artificially designed, so they are not really scars. They are more like tattoos, and I have issues with that.

I’ve heard opinions that the entire restoration of Dresden is fake. How do you feel about it?

‘Fake’ is too harsh a word because it’s hard to separate the interblended fakeness and genuineness of it all. But, well, it is fake since it’s all palaces but no aristocrats. Perhaps, in 10 years, it won’t be fake because people will live there and have offices, coffee shops, and so on. After a while, it all becomes ‘the city’.

The restoration of Dresden is fake because it’s all palaces but no aristocrats.

So, when did the reconstruction of Dresden finally end?

I’d say that it was in 2004, when the final element — the golden orb with the cross — was put on the reconstructed Frauenkirche. It was the moment they tried to honor the thousands of people who died in the destruction.

Germans have always had a hard time dealing with their civilian losses. With 6 million Holocaust victims, it is hard for them to say, well, we lost hundreds of thousands of civilians in that war, too. Part of the success in Dresden was to say they could rebuild and, at the same time, establish a way to rethink the atrocity committed by the Allies against the city.

Inauguration of the reconstructed Frauenkirche in 2005. Photo: John Macdougall / AFP

A view of Dresden centre from a drone. Frauenkirche can be seen on the left, and the Kulturpalast is in the centre. Photo: Depositphotos

Which reconstruction was more effective — the first or the second one?

It depends a little bit on where one is on the political spectrum.

I’m certainly not a fan of capitalist neoliberalism. I don’t like the attitude of ‘we’re just going to put a massive amount of money into rebuilding an urban landscape and make a success story out of it, albeit at the cost of making those weird buildings that don’t belong in our modern culture’.

But one could say that Dresden ultimately became a thriving city: it has cultural heritage, it has got its street life and its nightlife, parks, restaurants, museums, and exhibitions. The modern reconstruction, although it aimed to get rid of the Socialist heritage, did also solve a nation’s split personality problem.

And what about the disadvantages that Dresden has after rebuilding?

Dresdeners have problems typical for neoliberal cities: there is inflation, housing prices are too high, and all that. By ‘neoliberal’, I mean the separation of labour from living. Like, the cleaning ladies probably don’t live in Dresden. They have to take a bus, and it’s an hour and a half ride.

Dresden’s main non-economic problem is the trauma that hasn’t been worked through. It grows into resentment and weariness if you don’t work through it. In turn, those may worsen the conflicts within the local communities.

How do you overcome it? Gather neighbours, friends, family, or the entire city and work through it together. If you share your trauma with the people who recognize it, it gradually stops afflicting your life.

Why did Dresden become the center of the Neo-Nazi movement? Because the Jewish community’s trauma was ignored. Nobody invited the Jews back to Dresden (and it’s just one example of that).

Rebuilding after a tragedy is not just about finding money and designing a plan. It’s working through trauma and the memory of the tragedy that haunts places.

Rebuilding after a tragedy is not just about finding money and designing a plan. It’s about working through the trauma.

Was the reconstruction of Dresden about working through the trauma or just rebuild-it-and-forget-it?

It was a ‘rebuild and forget’ thing because the restoration was top-down.

What advice do you have for Ukrainians about rebuilding the country after the war with Russia?

In Ukraine, you experience massive destruction that we haven’t seen since World War II. And we don’t even have literature on how to deal with that. War is a trauma. And working through it is something Ukrainians will have to figure out.

My only and very humble advice would be to think about such processes by which communities meet and discuss their problems. The reason why working through the trauma is often ineffective is that the nation-state comes in and says this is how you need to remember this battle or our great heroes. How to make peace with the trauma and respectfully engage with the terrible things that have happened in the local communities — that is the question that Ukrainians have to answer themselves. And it is a years-long process.

Cover photo: Depositphotos, Wikimedia Commons

New and best