An Empty Museum: How Post-war Beirut Failed to Become New Paris

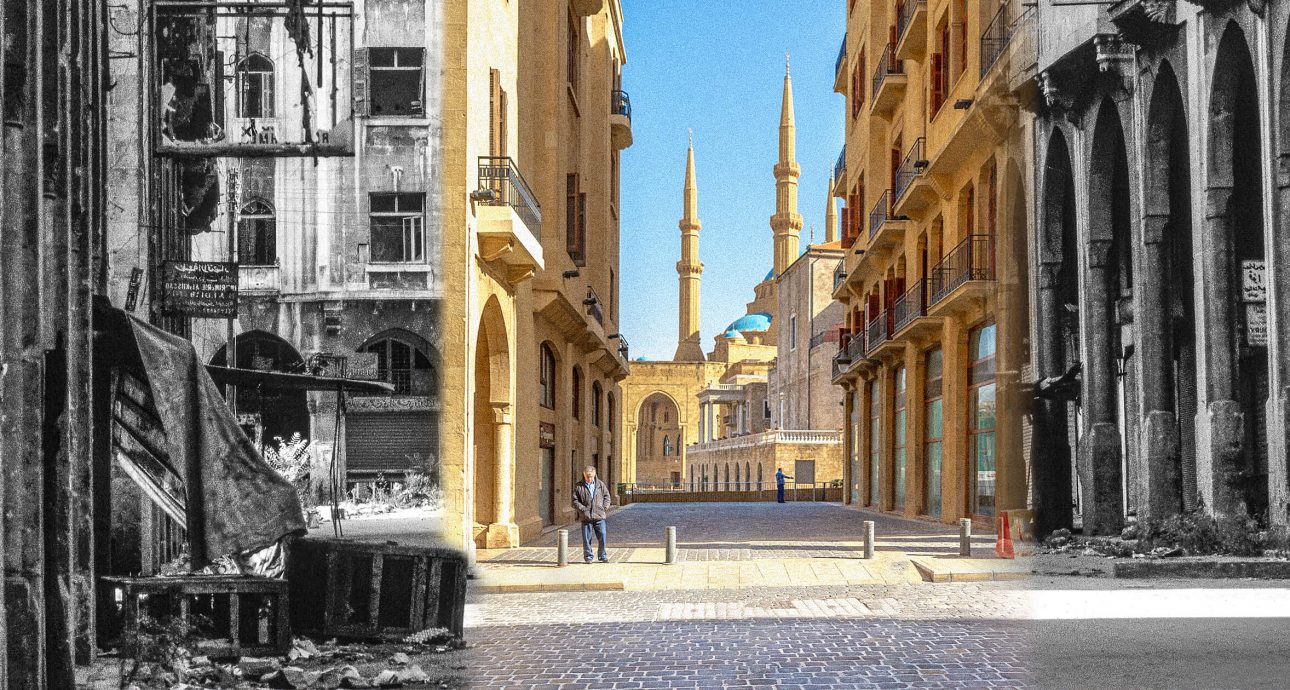

The Lebanese Civil War continued for 15 years, during which the frontline split the country’s capital in two. Urban fights turned the city into an enormous squat — the buildings were damaged by shelling, and the line of demarcation was overgrown with weeds and trees.

After the war, city authorities bought out the buildings in the central part of the city to speed up rebuilding. They had a grand vision of reconstructing Beirut as the Paris of the East it was in the early 1970s. However, their plans fell through. Beirut failed to become a new Paris. Moreover, it turned into a desolate husk of a city too expensive to live in.

Lilet Breddels, an Amsterdam-based researcher, helped the administration of Lebanon’s capital to rectify the mistakes made while rebuilding. She told Bird in Flight what the official did wrong and why the botched development was harmful to the city and brought about social disasters.

What was Beirut like before the war?

In 1975, the city was in great shape. People called it Paris of the East. It attracted Europeans who wanted to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of the Middle East, as well as tourists from Dubai and the Gulf countries hungry for a taste of a different life. Beirut had it all back in the day: cinemas, discos, culture, exhibitions, theatres, parties, alcohol, and whatnot. In terms of everyday life, the city flourished.

From the architectural perspective, however, it was old and neglected. It had lots of six- and seven-storey buildings with arched windows and doors and numerous balconies. Also, there were many modernist buildings which clashed with one another stylistically. You can call it a mix of Arab motifs and Western influences from France.

Naturally, there were some excellent architectural specimens. Nowadays, they are either protected as heritage or lie in ruins.

Beirut in 1973. Photo: Jose Nicolas / Hans Lucas via AFP

How was the city destroyed during the war?

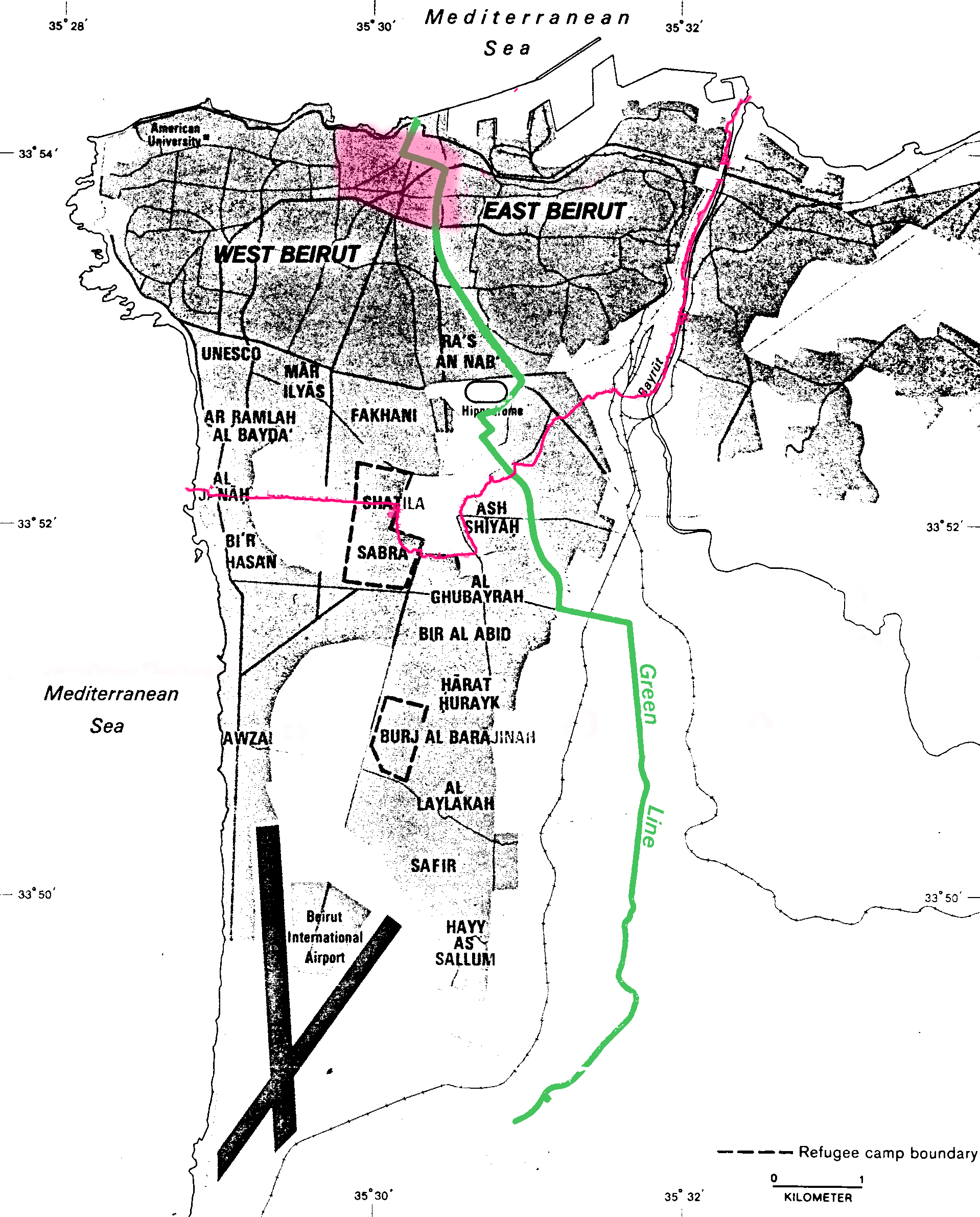

By shelling, mostly. The most damage was done along the line of demarcation — the so-called Green Line that divided the city in two. Both sides fired their weapons; snipers were stationed in the high buildings along the line. There was fighting in other parts of Beirut, too.

What was this Green Line like? Something akin to the Berlin Wall?

No, it was arbitrary. It was more of a buffer zone between the Christian and Muslim Beirut that ran along a couple of major roads. The Green Line was exposed to fire, so nobody went there. In a while, it became overgrown with greenery, with nature even taking over the houses. It literally was green. A rather romantic picture, that green corridor in the otherwise ruined city.

The officials rebuilding the city should have capitalized on that space and turned it into a park, but they decided to get rid of it.

Is there nothing left of it?

Not quite. It is still noticeable in some places.

The walls of many buildings still bear the holes from shell impact — those are noticeable by the naked eye. Some structures damaged by the war became memorials of sorts, like the Holiday Inn hotel riddled with holes from shells and bullets. Despite having perhaps hundreds of plans for its reconstruction, city authorities still don’t know what to do with it. It is located on the Green Line, actually.

What was the scale of destruction when the war ran its course in 1990?

The destruction was extensive, but no official estimates were made.

Many houses were severely damaged but survived. Instead of repairing them, which was totally doable, the officials decided to tear them down, especially those in the central part of the city. Overall, about 80% of buildings in the city centre were dismantled after the war, even though that area suffered more from neglect rather than shelling. The decision to demolish was in part political and partly due to the authorities’ ignorance. Quite a few genuine architectural heritage assets disappeared as a result.

Architectural landmarks in the central part of the city were demolished after the war, even though they could have been repaired.

Central Beirut during the war in 1982, about 100 metres west of the Green Line. The Grand Théâtre des Mille et Une Nuits is in the back. Photo: Jose Nicolas / Hans Lucas via AFP

The view of the Green Line in 1990. Photo: Nabil Ismail / AFP

How and when did the restoration begin?

Immediately after the war ended.

However, the war ended in Beirut, not in Lebanon. Conflicts like these usually end in a peace treaty, but people just stopped firing at one another in that case. No documents were signed or statements made. Still, no restoration can start without some agreement because nobody knows what they are paying for. In general, people just went on with their lives.

Still, the government decided to rebuild the capital as fast as possible. The entire thing was overseen by Rafik Hariri — a billionaire and then-Prime Minister of Lebanon. The city’s centre was slated for reconstruction first, as it was a trade and tourist hub before the war. The authorities developed a general plan and guidelines setting relatively high standards for the reconstruction. Among other things, they stipulated construction materials and even the distance between the buildings. It was all good and well, but the owners of those buildings in the central part of the city couldn’t afford to rebuild according to such standards — it was too expensive. On the other hand, they couldn’t violate the guidelines either.

The government ended up buying the city’s centre and establishing Solidere (Société Libanaise pour le Développement et la Reconstruction du Centre-ville de Beyrouth) — a public-private partnership tasked with rebuilding it. Among the company’s shareholders was Prime Minister Hariri, so it could do whatever it pleased.

How did they buy out the entire centre of the city?

The owners were selling their properties, intending to buy them back later. They were also paid in Solidere shares, which were said to appreciate soon. Nothing of that came to pass. Real estate prices went through the roof in the newly reconstructed city centre, and buying back one’s shop became plain impossible. Meanwhile, the interest on Solidere shares was at rock bottom.

Did people protest?

They did walk out, but their protests yielded nothing.

Where did Solidere get the money for the reconstruction?

The money came from the government and private investors.

Did Solidere operate only in the centre of the city?

At first, it did, even though there was a big plan to rebuild adjacent districts, too.

Because of stringent guidelines, Solidere had to pay through the nose for its central Beirut development, and so it started erecting high-rises in other districts to recoup. Now the central part of the city looks like a desolate museum surrounded by high-rises.

The new centre of Beirut looks like a desolate museum.

Other parts of Beirut remain untouched. Buildings are still in terrible condition there.

Why is the city centre empty?

The reasons are many.

First, the centre is well-developed and has a luxurious look. The rich from the Gulf countries have purchased all the real estate there, but they rarely come to visit Beirut.

Second, the authorities decided to turn it into a replica of Paris of sorts. Souk, the old market, was converted into something akin to a mall, which drove the remaining few locals from this area.

Third, governmental buildings were crammed into the city centre, too. The governmental quarter is occasionally closed to the public for security reasons.

Eventually, locals just stopped going to the city centre, and it became deserted.

A map of wartime Beirut. The Green Line is marked in green. Pink are the city centre reconstructed by Solidere and the city limits of present-day Beirut. Image: based on Wikimedia Commons

So, the city centre reconstruction plan fell through. Why didn’t the authorities do anything to prevent that?

Because the gentrification issues surface only after a while. The reconstruction had positive sides, but those just obscured the setbacks. For instance, international brands entered the city, and coffee shops started popping up. The city centre rose from chaos to becoming a high-class location. People enjoyed that.

However, the problems surfaced when the economy started slowing down in 2008. Shops started closing down. Their owners boarded up the windows. Within just eight years, the city centre was empty. It gradually revives already, though, with coffee shops opening up where boutiques used to be.

What about the high-rise districts? Are they flawed, too?

Yes.

Some buildings there were designed by decent architects, but the development became a chaotic mess for the lack of planning. The same is true for roads there. Public spaces could use a plan, too. In short, the development there is just randomly arranged private properties. The involvement of world-famous architects didn’t make it any better because they worked out of context.

Another problem is the low-quality materials used in construction. When a blast shook Beirut two years ago, those buildings caused more deaths than the old ones.

A high-rise by Herzog & De Meuron in the centre of Beirut. Photo: Jean Isenmann / Only World / Only France / AFP

Why didn’t those ‘decent architects’ help plan the city?

They tried, but their efforts ended in nothing because of the city officials.

Once, my colleagues and I issued a call for proposals to improve public spaces in Beirut. The City Hall asked us to present the winning submissions. Then, they suggested we join the Public Planning Committee. You know what? My colleagues refused, convinced that the city authorities were corrupt. They were positive the officials just wanted to use our names. I beg to differ, but I can’t do anything by myself. This is why Beirut still has no Urban Planning Department.

Did City Hall implement the winning projects?

Not really. I mean, they did set up public gardens where people still can grow their food and spend evenings together.

You see, we wanted to influence city residents, make them speak up, take action, stay in the country and do something for Beirut instead of emigrating. Last year, my team and I held a masterclass, which 60 students from six universities took. This is something to brag about. I place high hopes on the new generation. Still, the country and the city are broke, so now it’s not the time to implement those ideas. When the system and the regime change, our groundwork will pay off.

Where there anything positive about the reconstruction?

People who used to fight one another started living together. If a city gets divided by the war, there is also a decision to be made after the conflict ends: should you mix those groups of residents together or break the city into zones? In Beirut, the problem took care of itself when the people settled in opposite parts of the city.

Present-day Beirut is a melting pot of cultures. In one district, you find yourself in an Arab settlement; in another, you enter a European city; and in yet another, it’s an Armenian quarter.

I might be romanticizing the current situation because I’m a foreigner, and I’ve never been in the southern districts where Hezbollah runs everything. It’s dangerous there.

When did the reconstruction end?

Arguably, it did in 2009, when the rebuilt Souk market was opened to the public.

The city centre built by Solidere. Photo: Ramzi Haidar / AFP

Was there any chance to handle the reconstruction differently?

I think there was. If only the authorities didn’t get ahead of themselves and just discussed all the issues with the public. If only more than one company were tasked with reconstruction. If only the process were public. If only the authorities had created a real estate owner and developer committee. If only they didn’t have business-driven motives, the situation would have been much better now.

To their credit, the officials gradually started admitting their mistakes. Solidere’s current head of city planning is a 40-year-old university professor. He joined Solidere to help his country. He publicly admitted it was wrong to take into account only the elite’s interests. Now the company is trying to make amends, including by lowering real estate prices in the centre of the city.

The developer has publicly admitted it was wrong to take into account only the elite’s interests.

You held the Towards an Architecture of Peace studio, during which you explored how architects can contribute to peace efforts in the post-war territories. Is this even an architect’s job?

Yes and no.

Architects are taught to build and think about aesthetics and how to keep buildings from falling apart. However, they are also responsible for the outcome and how their creations are used.

When architects know or could learn that their client is corrupt and the funds allocated for construction were used inappropriately, they are also responsible for the outcome.

My Towards an Architecture of Peace project is to make lawmakers take architects seriously and involve them at all stages of construction, not just at the very end ‘to make it look pretty’.

What lessons can Ukraine learn from the reconstruction of Beirut?

The outrageous thing about the restoration of Beirut was that it was handled by just one company. Draft Law No. 5655, recently voted by the Ukrainian parliament, gives the green light to similar things. I’d also like to warn you that power concentrated in the hands of a narrow circle of people does not bode well for reconstruction.

You need to create a system of monitoring and control — an agency that will include representatives from all stakeholders. Also, it’s a good idea to involve active members of the public at various stages. Perceive city residents as partners — this is the only way to avoid dissent in the future.

Also, create a strategy for handling buildings that have become symbols of war, and don’t demolish more than you have to. These are the lessons of Beirut.

Former Holiday Inn hotel, one of the symbols of the war. Photo: Oliver Berg / dpa Picture-Alliance via AFP

Having a plan won’t hurt either, in my opinion.

Sure, but it’s more of a vision kind of thing. Planning should be flexible in Ukraine because nobody knows how many people will return to the country and when it will happen. You can start developing plans and the system as well as surveying the city residents now. It will give people an occasion to think about the future after the war.

In discussions about the reconstruction of Kosovo, you may often hear, ‘We weren’t ready for peace’. That’s very true. Without a plan, the people who return home after the war ends begin to chaotically develop the cities.

Cover Photo: Depositphotos, AFP

New and best