Homeward and The Wild Fields Producer Volodymyr Yatsenko: “Karpenko-Karyi University Needs to Burn Down”

Yatsenko’s latest work — Homeward (directed by Nariman Aliev) — is hitting the cinemas on the 7th of November. The film tells the story of a Crimean Tatar family that lost a son in the war on Donbas. Homeward was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival in May and selected as the Ukrainian entry for the Best International Feature Film at the Academy Awards four months later.

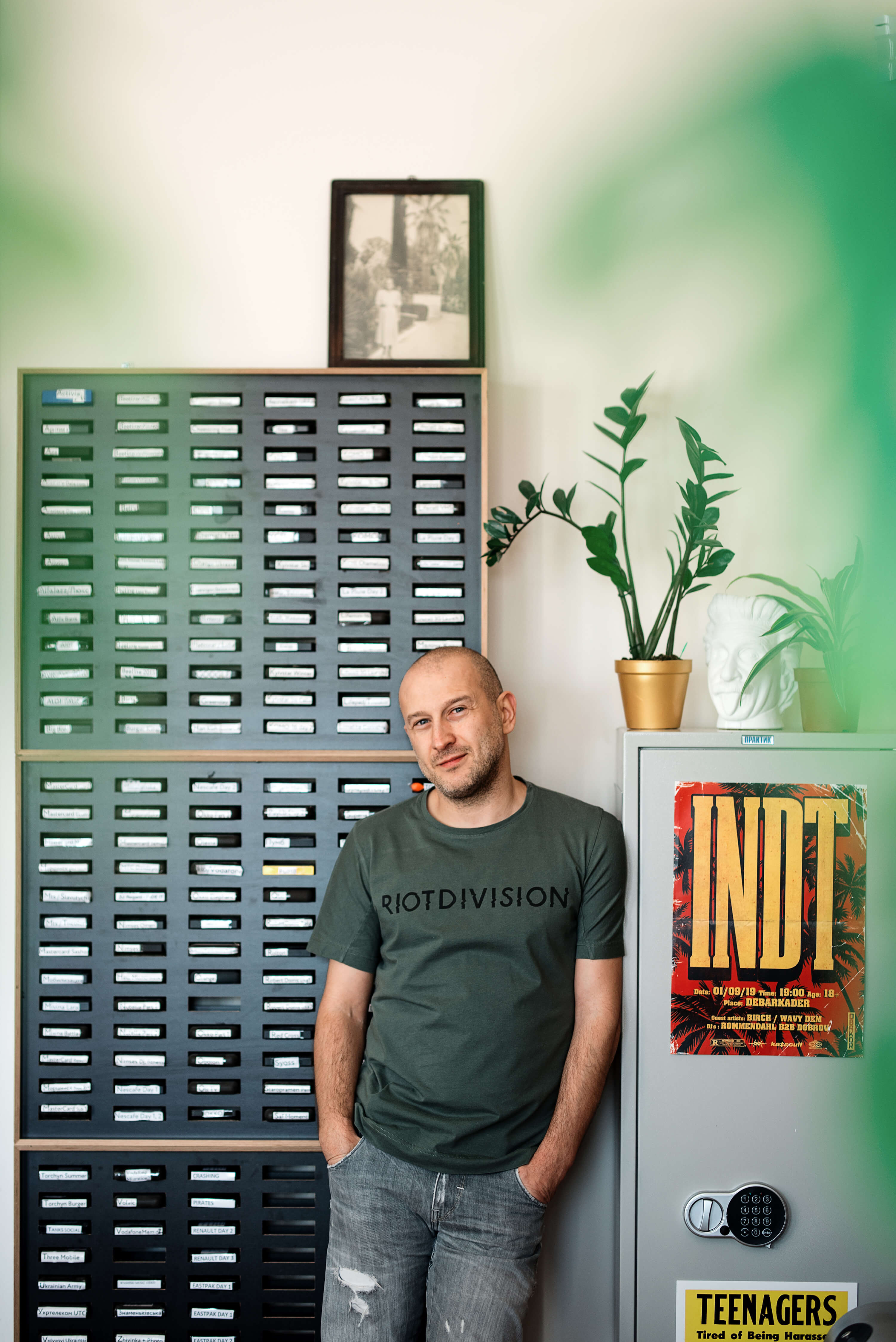

Volodymyr Yatsenko met with the Bird in Flight journalist in the office if his LIMELITE production house accommodated in the former hydropathic clinic’s building. The producer told us which topics Ukrainian cinematographers feared to tackle and why he didn’t like stories about Russian villains and Ukrainian patriots. Also, we discussed the difference between the amateurs with whom he made films and those with whom he declined to.

On one occasion, you said that the Ukrainian New Wave became successful. Wasn’t it a hasty judgement?

No. According to the statistics from the Ukrainian State Film Agency, Ukraine has been represented at all global film festivals lately. Nothing of the sort has ever happened to our poor country.

It feels like the festivals accept Ukrainian films not because we have made something significant but to see how a third-world country at war lives.

Yes and no. It takes gorgeous looks for pictures about the third-world countries to be invited to festivals. Ukrainian cinematography conveys a strong borderline state. It gives Europeans an opportunity to see what they fear.

Do Ukrainian films have those gorgeous looks?

They look OK. We watch many other films at the festivals, and the Ukrainian ones often look as good as those from other European countries.

What is your opinion on patriotic films like The Secret Diary of Simon Petliura, Cyborgs, Censored, and The Rising Hawk?

I have none. I believe they lack vitality and depth of characters.

And what about the most successful Ukrainian comedy — Crazy Wedding?

I don’t like it because it’s an utterly stereotypical parade of our society’s painful traumas.

What would you prefer if you had to choose between filming a comedy in the vein of Crazy Wedding or a patriotic picture like Censored?

(Thinks) I’d rather make a comedy, as I would suffer less for it in hell.

Most Ukrainian patriotic films are bad because everything about them screams make-believe. In one scene, people armed with only assault rifles destroyed enemy tanks. Thinks like that feel awkward. I was often on the front lines, so I know that everything is quite different there.

I feel bad for people who died defending our country, and I believe we owe them our lives.

Comedies are just comedies — they have nothing to do with the blood of soldiers killed in action.

Talking about firing assault rifles at tanks, do you mean Cyborgs?

No, I’m talking about a bunch of different films.

I’d rather make a comedy, as I would suffer less for it in hell.

Will the Ukrainian cinema be able to find new themes once we finally overcome this trauma?

If the Ukrainian cinema survives, it will. Our country is totally unpredictable. Nowadays, we have no understanding if the new government wants to manage the Ukrainian cinema. What will happen to state funding? What themes will the experts support in films?

It’s hard to discuss new themes: the Ukrainian cinema reflects on the war, albeit still has to learn to work with simpler themes.

Which of the recent Ukrainian independent films resonates with you?

My Thoughts Are Silent by Antonio Lukich. Although I’m kinda on the fence about this film, it does have the pain and irony characteristic of the time.

It was criticized for being more like a set of skits.

I believe there is an overarching story there. The critics are right, though—the film doesn’t really come together as a coherent character journey. As a director, Lukich has a good attitude and a feeling for self-irony. His film is an unusual attempt at comedy built on reflection. Crazy Wedding is about laughing at others, for instance. Meanwhile, Lukich is ironic about his own shortcomings, which is excellent.

Did you approach him for a collaboration?

He needs to choose us, and we need to choose him. So far, we just discussed what was he was interested in. Filmmaking is a thing that takes a long time to play out.

You are forty-two. Do you feel any generational gap while working with the directors ten to fifteen years younger than you?

No. What concerns me, though, is that the new generation of Ukrainian directors has got used to the government giving away money left and right and letting them get away with mistakes. They didn’t live in the times when three films were made in Ukraine annually (all about cossacks, baggy trousers, and all that stuff), and the cinematographers lived for getting hammered in the House of Cinema’s buffet.

Many people believe they will get money just for being talented. They are not prepared to go abroad to fight for the right to fulfil themselves in their field there. And here, they wonder, “Why can’t they give us money?” It’s not that difficult to figure out, guys!

Who said that?

I don’t want to name them.

Did Nariman Aliev and Antonio Lukich say that, too?

No, they do understand that everything in this life has a price.

Directing is a Golgotha. As a producer, I can be involved in multiple productions at once. At the same time, directors have to spend five to seven years making just one, and it doesn’t guarantee success, mind you. A distributor puts your film on the wrong dates, and you’re done — nobody will watch it.

I believe the people having only directorial education need to be legally banned from directing. A second degree is a must for directors. If you start studying direction at sixteen, you will have nothing to say in the field because you don’t know what life is about. There are definitely exceptions, but those are few and far between.

I believe the people having only directorial education need to be legally banned from directing.

How old should you be to become a director?

It’s not about age. You need to experience the trauma, discovery, and loss that people endure. The second education guarantees that the future director is over twenty-one and gets at least something about life.

Nowadays, direction students are all excited boys and girls. However, all they listen to over the five years of their studies is how their elderly professors used to get hammered with Parajanov. The newly minted directors thus graduate with just one short film in their portfolio, and then they start waving their diplomas around and demanding money. Some of them are indeed talented, albeit they are yet to master their trade. They go on to shoot another short film for state money, and that’s it.

To become a director, you must make all sorts of mistakes essential to your development, which takes at least five or six short films. Only then there is a chance the director will show their talent.

Without experience, you will botch your first feature film despite all your talent because filmmaking combines creativity and production.

You filmed The Wild Fields with Lodyhin, even though he had hardly any previous experience. You are contradicting yourself.

There are no contradictions here. I saw how Yaroslav prepared for shooting. I saw he was ready to listen. Besides, we had assembled a dream team at the time, so our project worked out great.

Are Karpenko-Karyi alumni good directors?

They are horrible. I graduated from the Karpenko-Karyi University as a producer (and before that, I got a regular education at the Institute of National Economy). I say it needs to burn down for another to be built on its ashes. The Soviet-era guidance system that it sticks to is just unfeasible. You won’t see Loznytsia, Nariman, or Lukich giving lectures there. Those teaching there are all wonderful people, but they are in their sixties, and most of them have shot only one film (and many have none). In my view, they are just ruining their students’ lives, and it’s a waste of our country’s money.

Besides, you can’t study for five years to become a director if two years are enough. At the American Film Institute, you have to shoot five films and participate in 140 projects over two years of studies. If you have a talent for that, you move forward; if you don’t — you’re out, sorry.

Could you name a modern-day powerhouse Ukrainian director?

It’s a complicated question. No Ukrainian director has made over three pictures. Slaboshpytskyi shot one film and then went off the radar for many years. Many younger ones have recently had their breakthrough, but it’s hard to say what becomes of them.

Naturally, there’s Loznytsia, but he’s no longer a Ukrainian director. He is a man of the world — despite having a Ukrainian passport, he lives in Germany.

Therefore, I can name a few young directors as the best: Nariman, for instance, Lukich, and Maryna Stepanska, perhaps.

Teachers at Karpenko-Karyi University are just ruining their students’ lives, and it’s a waste of our country’s money.

You came to filmmaking from advertising. Was it difficult to adjust?

No. Way before the ads, I shot films in Moscow. Then, I transitioned to advertising videos because they ceased making films there. Opening our production house, Anna Sunden and I understood that we wanted to make money and become the best in the field. And we did it.

We projected our experience from the advertising field — organization, service, straightforward processes — onto filmmaking. We were shocked to see how some film crews worked: the food on the set was terrible, and people weren’t even paid. I can’t hold the people for whom I didn’t provide the appropriate conditions 100% accountable. However, if I did provide everything and someone f*cks up — they are out immediately.

Don’t you miss advertising?

No. Over more than 14 years of LIMELITE’s existence, I spent over 1,000 production days on the set, which is enough to shoot 30 films. I know everything I need about ads — I see no point in developing further in this field.

Producers play a vital role in filmmaking, especially at the development stage. That’s why it’s so exciting to work there. It’s a creative occupation that lets you bring your ideas to life. For instance, you can approach the director and say you want to shoot a specific story. It’s a great joy to help a director create a world that didn’t exist before. What has started as an idea suddenly becomes a film that people can watch.

How much are you involved in LIMELITE’s operation now?

I don’t film ads anymore, but I’m still responsible for financial planning, back office, and finances. Anna Sobolevska and I are currently planning to establish a separate entity dealing with filmmaking exclusively. It will share its back office with LIMELITE but have a different focus.

If you had to choose between filmmaking and business, which one would you give up?

The business has never been a goal in itself for me. If I could make films the way I want and for as long as I want, I would abandon the business. Filmmaking doesn’t earn me money, though, so I have to run a business.

Can a producer currently make a living making films in Ukraine?

Not yet.

How much of your own money do you usually invest in a film?

EUR 10,000–15,000 at the development stage. This includes screenplay development, finding a producer, and international pitching trips.

We never take 100% state funding, so we also have to invest in production. For one film — a sci-fi short — I had to cough up about $70,000.

How much did you make from The Wild Fields?

Nothing. I was $120,000 in the red, which met my expectations. In the case of Homeward, I believe I can turn a profit, but it’s too early to comment on that because the sales continue. However, the fact that the company signed the film makes me hopeful. It’s a breakthrough for our country because no Ukrainian producer has ever inked a deal like this.

I currently see film-related expenses as an investment in my professional development (I expect to earn from making films later). The thing is, nobody in Ukraine knows how producers should work —everybody is at the learning stage.

Where do you find ideas for films?

Everywhere. For instance, I got an idea for Eternity from a short film. Another source of inspiration is screenplay contests, where I’m often invited to sit on the jury. Usually, 98% of the screenplays I see there are a hot mess, 1% are just ludicrous, and the last 1% are readable.

What kind of stories capture your attention?

There are so many of them. For one, I like exploring coming of age as a theme. People under the pressure of circumstances is also my favourite one. And I love science fiction, too.

I would gladly make a smart rom-com about real-life people. Shooting a horror flick in the vein of

“Little Ukrainians” are featured in our cinema — Crazy Wedding is about the complexes of the “little Ukrainians” living in villages and suburbs. However, we have no films about regular city dwellers.

Usually, 98% of the screenplays I see at contests are a hot mess, 1% are just ludicrous, and the last 1% are readable.

I watched Dogman once — it’s an ideal adaptation of Dostoevsky. In it, a “little man” working as a pet groomer is trying to earn the love of his well-to-do friend. And then that friend turns his life into hell. A perfect story, and wildly intimate, too! Why can’t we make a film about two simple guys from Troeshchina? Are we different in the head? Don’t we have two arms and two legs?

Also, I’m definitely eager to explore the post-traumatic syndrome and the disappointment our society is going through. Perhaps, it can already be stated that the Revolution of Dignity was a shot off the mark. Sure thing, the fight we started in 2014 is not yet lost, but what we see now is a reaction to the revolution. It’s a subject worth reflecting on, too.

What’s wrong with the screenplays you get?

They are unprofessional. The people writing those screenplays are not screenwriters. Most of them are Karpenko-Karyi University alumni, which is laughable in itself. Screenwriting is something that takes mastery — there is a technology to it. Meanwhile, our screenwriters are prone to reinventing the wheel every time.

Tell us about the strangest screenplays you’ve ever read.

There were a lot of them. Mostly it was a mix of the ATO and witch cossacks rescuing a girl from the fire. Also, Ukrainian Insurgent Army warriors and Russian villains are always present.

There have been lots of detective screenplays, too. Like, an honest but poor detective somehow arriving in a town full of vampires at best or alcoholics and maniacs on a killing spree at worst. Then, the protagonist gets into a love affair with a poor teacher who eventually dies at the hand of a maniac or an alcoholic. Another problem is that our screenwriters can’t even competently describe characters, limiting themselves to “he wore chequered trousers”.

You feel sad and ashamed while reading it because the person who sent it to you invested time and effort in it.

It’s great they put effort into writing at least something like that. The problem is that few of them are willing to put everything at stake for the sake of their profession. After all, you need to study, grow, and learn the trade. There are people ready to learn, but those are few and in great demand. It just goes to show that the Ukrainian cinema’s sorest issue is amateurs.

What should an amateur do for you to notice their screenplay?

Tackling the theme that resonates with me is good already. However, they also need to write in a way that I can read. I am reading a story, and it either entices me and resonates with me or it doesn’t. That’s all.

You mean that picking a screenplay is a subjective thing.

Sure, filmmaking is totally about subjectivity. It lets you express yourself the way you are.

Which themes are taboo in Ukrainian cinema?

LGBT is one example. We are much like the many post-Soviet countries in this regard. And Then We Danced, a Georgian film about gay dancers, drew much negativity in Georgia. The Georgians keep shaming it to this day, like, no Georgian can be gay. As a result, And Then We Danced was nominated for an Oscar as a Swiss film.

The situation is even worse in Ukraine. The government won’t allocate money for it, and nobody would watch it anyway — unless it’s about the gay Ukrainian Insurgent Army fighter, that is.

Also, I find it hard to imagine a Ukrainian film about someone with PTSD in the vein of Taxi Driver. I’m not sure anyone could get money for something like that. And our directors still keep guessing whether the Ukrainian State Film Agency’s expert board will approve their screenplays.

And you guess correctly?

I’m not even trying.

But most of your films got state funding. So have figured it out.

Our winning projects were robust. If the new government changes its approach to selecting films, I will pursue my filmmaking endeavours in another country.

Would you make a film about LGBT?

I see no problem in that, as long as I like the screenplay. It’s as easy as I like the story—I make the film.

I can not only film a picture about LGBT but go even further. TheBabel once ran a story about a lawyer who defended Yanukovych. I discussed a film adaptation of the story with the publication’s editor-in-chief Hlib Husiev at the time.

I remember it. In it, the lawyer has nothing under control — it doesn’t even matter if he wins or loses the case. Why did this story devoid of drama resonate with you?

Say, you have an arbitrary lawyer of an arbitrary Yanukovych. He is a “little person” who just wants to get his cut. He is under constant pressure from all sides: the Security Service of Ukraine and Ukrainian society, the client (basically, FSB), and the Americans. And this person needs to survive somehow. Besides, he needs to defend the arbitrary politician who committed crimes against his nation. It is very intriguing.

Have you acquired the rights already?

No. We are currently negotiating the purchase of the rights to the investigative report. I still have doubts about it because I’m unsure if I can find a screenwriter to write this story and a director to film it. We have no people who could competently make courtroom dramas.

How much is it?

Not a lot — less than EUR 10,000.

You often slam amateurs but keep working with them yourself. Lodyhin is a radio presenter and producer. Marysia Nikityuk, with whom you worked on Homeward, is a journalist and theatrologist by education.

I don’t have a dozen professional screenwriters to choose from. Therefore, we work with those having talent and at least some capacity to convey it.

Is it to say that some amateurs are worth trusting, and others aren’t?

If we’re talking about Marysia, she had a feature film under her belt to show her competence. Besides, she wrote a lot of screenplays. Marysia is what she is: somewhat weird, somewhat traumatized, but definitely intriguing and alive. Meanwhile, 95% of screenplays I get have the same problem — they are lifeless.

Are you an amateur or professional?

I became a professional over the past year that saw the release of The Wild Fields and Homeward. I have made four films, which means something.

Over these two and a half years, I came a long way, taking numerous producer and other courses. I put the business on the back burner, put my company at stake, and assumed all the risks. I learned and invested my own money in films. Whether it was for better or worse is another question.

How many films does a producer need to work on to be considered a professional?

At least three. The people who released one film are still amateurs, even if with a better understanding of their trade.

Let’s talk about your films. You have The Wild Fields, Homeward, Atlantis, and Invisible. Which one makes you proud the most?

I’m proud of The Wild Fields the most because it was my first [feature film], and we poured a lot of love into it. The second-best is, perhaps, Homeward.

Did The Wild Fields turn out as you envisioned it?

Almost. We shot enough material for two hours and forty minutes but had to cut it to two hours. As a result, the picture had big problems with its structure. Besides, we were too attached to the action as described in the novel but missed many details anyway. I believe Voroshilovgrad would have made a genius miniseries of four episodes — it was tough to cram a book into a two-hour runtime.

When did the picture’s structural problems become apparent?

At the editing stage. We had been editing it for six months (which is very long), endlessly cutting things and removing certain plot lines. You throw away a scene, and then it turns out a character’s line in the previous scene doesn’t work anymore without that fragment. We had to make tough decisions, and Lodyhin and I own each.

Voroshilovgrad would have made a genius miniseries of four episodes—it was tough to cram a book into a two-hour runtime.

Did Zhadan like the film?

At first, he wasn’t a fan, saying it wasn’t what he had written. Then he took it back.

Why did he change his mind?

We showed him one of the cuts on a small screen, and he didn’t get what happened there at all. However, he loved it once he watched it on a large screen.

You have said that Yaroslav Lodyhin is a talented director. Why did you cease working with him after The Wild Fields?

Because he has no screenplays. I will be ready to talk to him once he brings me a compelling story.

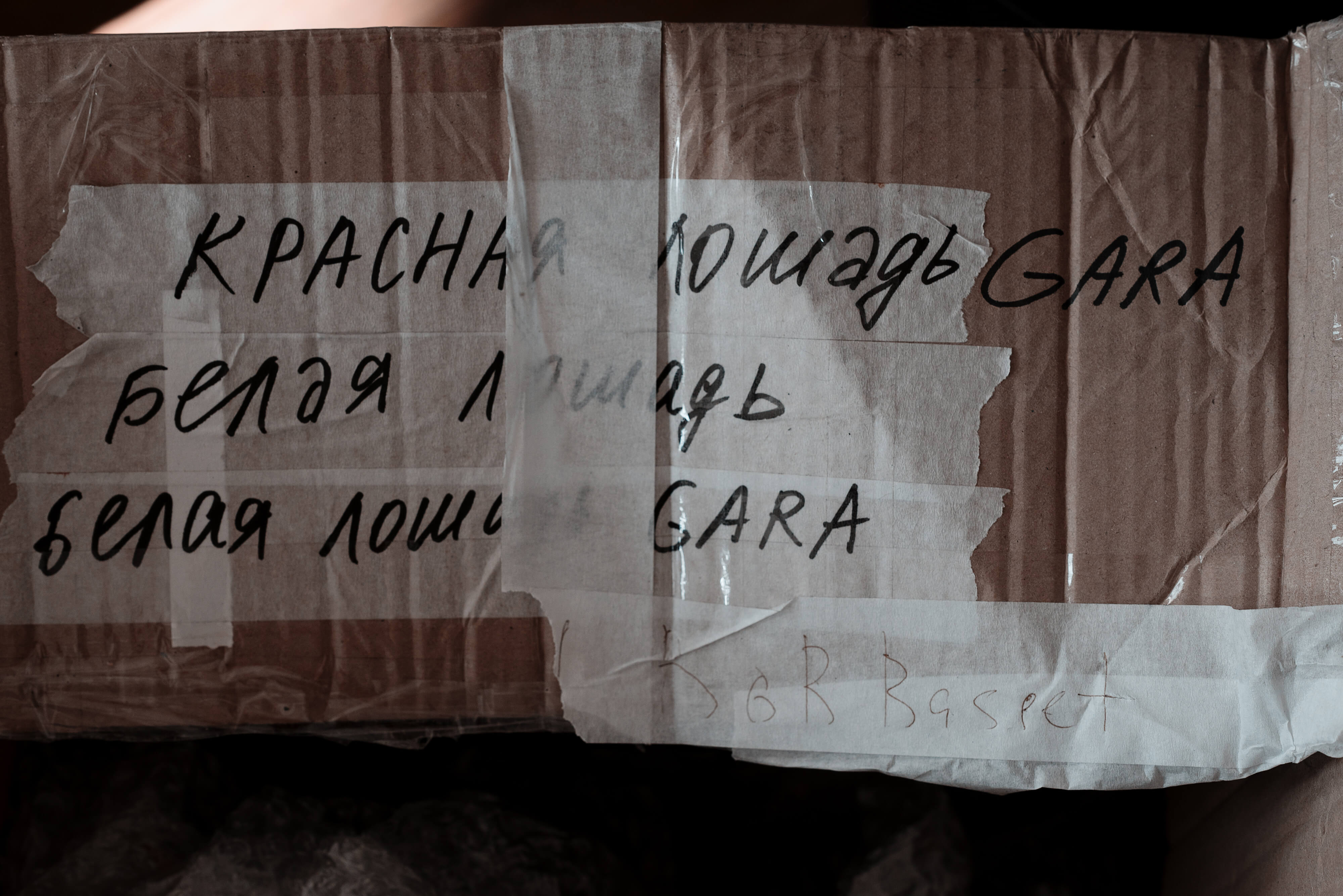

For instance, we have reached an impasse in the case of Orphanage. He wants to film it in Russian, and I don’t. It may happen that it won’t be filmed at all unless we arrive at some sort of consensus.

Director Nariman Aliev on the set of Homeward. Photo: Pavlo Shevchuk

The shooting of Homeward. Photo: Pavlo Shevchuk

Let’s talk about Homeward. Its protagonist, whose brother died, comes of age through the conflict with his father. Conveying the changes in such a character is difficult for an actor. Why did you decide to cast Remzi Bilyalov, who is not a professional actor, for the role?

Because we have no Crimean Tatar professional actors in Ukraine.

You could have cast a Crimean Tatar actor from Turkey and then redubbed him.

If we cast a cute guy who lived his entire life in Turkey and knew nothing about Ukraine and the war, we would have ended up having an entirely different film.

Also, Nariman filmed a brother, which was crucial. He knew how to work with the guy and elicit the state he needed.

We deliberately shot the scenes in the order of their appearance in the film for Remzi to gradually descend into the f*cked-up state we required. And it worked: the final scene was shot in just two takes.

Remzi agreed to shoot only because his older brother asked him to. The film is also his coming-of-age story in an almost documentary sense.

We deliberately shot the scenes in the order of their appearance in the film for Remzi to gradually descend into the f*cked-up state we required.

The film has a powerful finale, but it takes patience to watch it all the way through because all actors do in some scenes is scream.

Indeed.

As a viewer, I feel that amateur acting detracts from the film.

And I feel it doesn’t.

We live in an imperfect world. You have a specific amount of money and a specific cast, and you make the film with what you have. Many people don’t do things out of fear that the result will be imperfect.

It feels like your explanation for being unable to make an ideal film.

No. Some scenes were imperfect, but I do understand what could have been done instead. We made all the right decisions while shooting it. I don’t know a film, everything about which would be OK. Mind you, I’m not trying to defend Homeward. What I’m trying to say is that there are numerous circumstances one needs to reckon with, and it’s OK.

The film was selected as the Ukrainian entry for the Oscars. Moreover, your work was the only one submitted for the Ukrainian Oscars Committee’s consideration. Does winning this right without competition feel bitter?

No.

There was indeed no objective selection from a dozen films within the theme, but I still believe that Homeward is this year’s best film. In my view, nominating a film for an Oscar is a chance for a country to compete and learn something. God willing, we will compete with Vasyanovych’s Atlantis next year, and it will be much easier for us.

Meaning that you are now just practising?

Yes, and I will keep practising next year, and the year after, too. After all, the film’s victory at a major festival depends on many factors: how familiar with you the people are and the jury members’ attitude toward you. If you don’t put enough effort into your work for it to win, you will never succeed. Even if we are not short-listed, we’ll know we have tried. “Do what you must, come what may” is the Ukrainian cinematographers’ motto.

Photo: Svetlana Levchenko, exclusively for Bird in Flight