Sex, Death, and Ruins: WPP Jury Member about the Most Cliche Pictures

While serving as chair of the Documentary jury of the 2015 World Press Photo contest, a few days and a few thousand images later, I decided to take out a notebook and begin writing down all the various tropes, cliches, themes, subjects and pictures that passed by my eyeballs. Some samples from my notebook (which ended up running dozens of pages long) can be viewed below.

— Circus.

— Circus freaks.

— Brick-making factories.

— Grandparents (usually the photographer’s).

— Grandparents dying (usually on the last to second-last frame of the edit, an empty bed was portrayed — the grandparent had passed on).

— Dirty children, usually children in refugee camps, poverty stricken villages and third world countries.

— More poverty. If American, Appalachia or “rednecks” (look how funny these people are). If ‘foreign,’ usually black and white showing desolate scenes (look how poor these people are).

— Amputees.

— Some kind of sexual activity. Usually innocuous, but more about “Look, I photographed people having sex!”

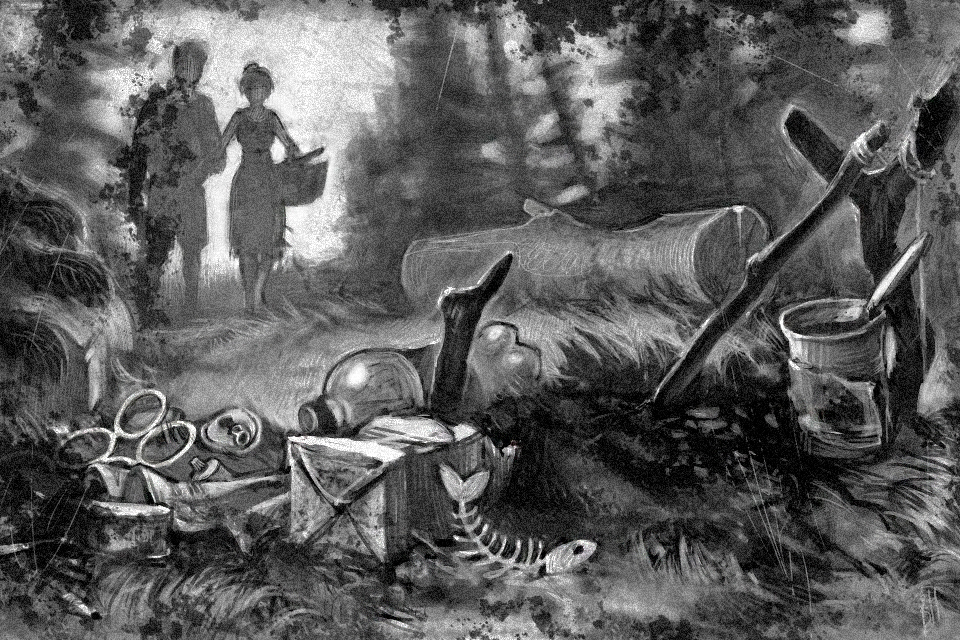

— Ruins, which can be broken down into sub and sub subcategories. American ruin: foreclosure, Detroit, wasted cities, economic ruin and decline. Ruin in the jungles, lots of greenery eating away at buildings. African ruin — decayed, forgotten or mistreated, human neglect. “Exotic” ruin — look how weird these people are, in their ruins! Ruined cars, planes and other machinery, not to be confused with ruined industrial estates or ruined and abandoned homes. War ruins: survivor among ruins, walking past ruins and living amongst ruins.

— Children.

— Children in refugee camps.

— Children in refugee camps playing.

— Children in refugee camps playing in muddy fields.

— Children in refugee camps playing in muddy fields with an oddly made or shaped football.

— Men with guns, and the women who nurture/care for those wounded men.

— Crying women, mothers, grandmothers, in some kind of emotional pain, signified by flailing hands or hands on face.

— In Gaza, images of the toppled mosque of Al-Sousi featured in the majority of stories submitted. Sometime just the toppled minaret, but usually with a woman, or a man on a mobile phone and even better, a man on a horse walking past the destroyed minaret.

— Horses: black, white, spotted. If a white horse, usually in some kind of pastoral, dreamy setting. Horses and donkeys, and people riding horses and donkeys were also contrasted in front of destroyed buildings in war, denoting the absurdity of war and daily life within a war zone.

In effect, I broke photo cliches down into these main categories:

1) Symbolic. horrors of war can be told through children in a destroyed zone, peace can be told through patriotic fervour, i.e. flags, camera angles of heroism (looking up), etc.

2) Emotional. Using images to provoke an emotional response in the viewer, as opposed to the depiction of the content. Blown up bodies denote outrage in the viewer, the recent death of somebody, like a grandparent, can evoke sympathy, etc.

3) Human identities. Using bodily gestures to denote what is happening. Facial gestures, hand gestures, posture, etc., all encapsulate and symbolize for the viewer what the subject is experiencing.

4) Western. Religious and other symbols of western art to signify to the viewer an emotional response. Most common, Pieta and religious symbols such as sacrifice (Jesus on the cross), “impressionistic,” classical art in lighting (Chiaroscuro, Renaissance, Rembrandt) regardless of where the photo or subject was from. Imposition of western aesthetic on a global story.

There were not just cliches and tropes used in the content, but also how that content was portrayed. Usually, a photographer used the shorthand of an aesthetic to drive home the point. For example:

— Black and white conversions (by a rough count in my notebook, at one point there were more stories submitted in black and white than color). Some typical traits of the black and white story, from a technical standpoint: dramatic shadows, vignetting and contrast, heavy grain.

If converted to black and white, the story was of a usually “serious” or “cause-worthy” subject. Meaning, black and white symbolized ‘serious issue.’ Black and white was rarely, if ever, used for light-hearted stories. If color, stories were usually about the oddities, strangeness, and quixotic behaviors of people.

— Usually billowing smoke in a large majority of at least one image of the story. Smoke always makes for a dramatic moment (and can be used symbolically — something dangerous, bad, foreign or destructive is happening).

So, in a very brief summary, this is to be taken as a lighthearted attempt at seeing what we all see. There is no way around the trope, icon or cliche, it’s a part of a visual vocabulary. And, of course, some stories will always have cliche, it’s just how you choose to tell that story. If we learn to see the potential (or lack thereof) of a certain cliche from the point of view of storytelling, I believe that we can distance ourselves from a simple visual presentation of the story and start really communicating, provoking the emotional reaction in the viewer, awareness and understanding.

What I found disheartening, however, was exactly that — our lack of imagination and ability to see what makes a good story. It should never be about the visual expression of that story, the story should dictate its form — but what we are seeing now is the complete opposite: photographers primarily decide how to show, but not what to show. We should not impose our aesthetic on a story. We need to start at the basics, to understand — what makes a story? Why are we invested in a story and what is our responsibility to the audience? How do we best service that story and present it to an audience, our ultimate arbiters of judgement and taste.

The media theorist Douglas Rushkoff speaks of the concept of flow and storage. We are in a saturated media age where billions of photographs are made everyday; this is the ‘flow’ of images, but what is their value to us, as we experience the human condition? Storage, on the other hand, represents the authentic. As professionals, we must dip into the ‘flow,’ providing an authentic voice to the jangle of images all around us. ’Storage’ is about having a clear focus of intent — and authorship, honesty, authenticity, and story follow.

A story cannot live on it’s own, it needs someone to tell it: this makes for a sublime conflict in today’s media environment. Intent and context are what will make a lasting work. In a not-necessarily-authentic world, audiences search for the authentic and find it in intent and context.

Today, the photographer, the storyteller, has the control of stories if he or she accepts that responsibility. You can tell a story, and, most importantly, you can show it to the world. We are not limited to a set of outlets. The outlet is you. If we can liberate the story from the iron grip of technique, and place focus on authorship, deception will fade and new readings of images occur.

Illustrations by Viktoriya Novoseletska.

New and best