Not Childhood Memories: The Project ‘How I Spend My Summer’ by Vita Buivid

An artist born and raised in Dnipro, also lived in Russia, and currently residing in Amsterdam since 2018. She is a resident of the Rijksakademie academy. She completed her studies in the Philology Department of Dnipropetrovsk State University and the Dutch Art Institute. Her works are held in private and museum collections in the USA, Finland, Sweden, and other countries.

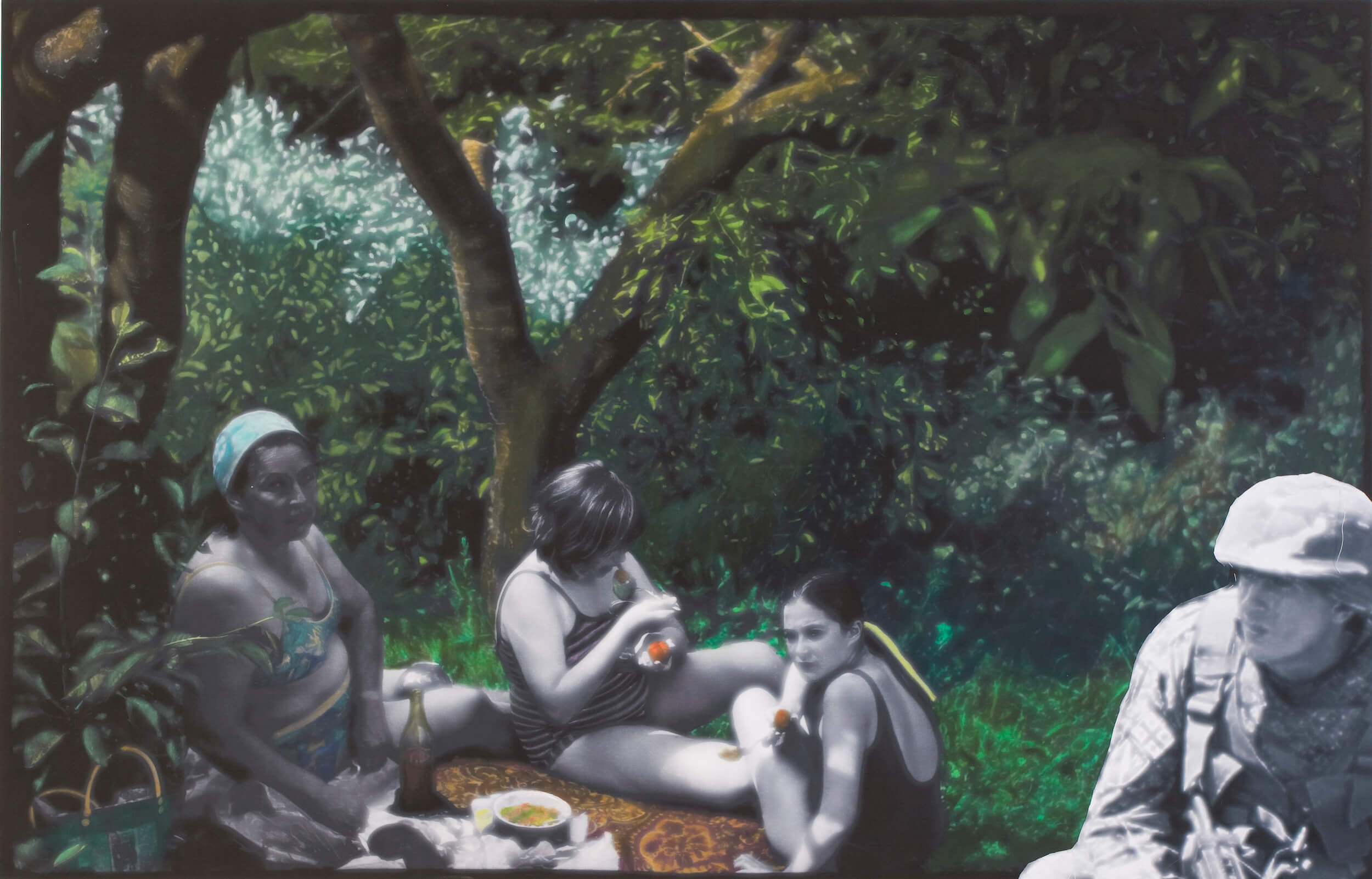

— I often work with family archives and hand-colored photography. Initially, I didn’t plan anything as serious as this project; I was simply coloring my childhood memories. However, one day while walking my dog in Moscow, I suddenly had a strange and unsettling feeling, as if I were in a city after a war had ended. That was the day the war in Ossetia began. I started stitching images of wartime actions into idyllic childhood scenes, although I wish I hadn’t. To be honest, at times, this project fills me with a mystical horror. There was a premonition of an impending war, but I couldn’t imagine it would be in Ukraine.

My father was a war veteran, so in our family, we always celebrated May 9th. Now, based on my own family story, I could write a book about how propaganda works, how it hooks us, how it plays on our sentimental vulnerabilities. Fortunately, I’ve encountered incredibly talented people in my life, such as Marlen Matus (the founder of the “Dnipro” photo club) and his circle, which helped me develop critical thinking early on. I believe that in the “How I Spent My Summer” project, this can be clearly traced: on one hand, there’s the sentimental aspect, and on the other, a critical one.

I exhibited this project in Moscow twice, and it was even nominated for the Kandinsky Prize. However, there was no significant critical reception or overt reaction. The project was just that—a project. But I closely tracked the increasing level of censorship, which spreads like a fungus, starting small and then growing with an abundance of invisible connections. What’s most horrifying is that self-censorship is added to this. And now, exhibitions are being censored and even banned in Russian museums.

I have been living in the Netherlands for a long time now. Yes, it is a safe place. It is believed that if you are not formally threatened, there is no need to despair or express any negative emotions. However, things have still changed. It couldn’t have changed. I found myself in a situation of “one among strangers, and a stranger among my own.” It’s challenging, and no matter what I say, my words can be misinterpreted. So, while I write what I think about this, it’s on the table for now, and I will publish it later.

Currently, I am a resident of the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. In practically all of my projects, there is an additional layer—the war. It’s as if it’s ingrained in my consciousness, impossible to remove. Of course, now I know how to talk about war without showing it. It’s a powerful experience. But it would have been better if it didn’t exist either.

At present, my experience of working with an international audience is limited to the Netherlands. Amsterdam is a multicultural city with many refugees from different countries. Almost every week, there are protests and demonstrations on the main square. Everyone has their reasons. The Dutch are very tolerant; they listen to everyone respectfully, express sympathy or concern about someone’s problems, and contribute to aid funds. Exhibitions often feature projects related to wars, genocides, and political repressions in different parts of the world. Art institutions provide a platform for expression, finance such projects, and host public discussions.

The fact that there’s always a war somewhere is undeniable. For some wars, we know nothing about them, and for others, we read the news briefly and then stop thinking about them. Can we blame anyone for this? People live their lives. Sometimes it’s just a protective reaction of the organism, as everything alive is focused on survival. The fact that everything can change in an instant is also true. But what to do with indifference, I don’t know. I don’t have an answer to that question. We just need to understand that war is not only within us, unfortunately. And it’s strange to expect too much emotional response from people who are far from it.

With the onset of full-scale war, my works haven’t changed; what changed is how I present them. Last year, I exhibited this series in Amsterdam and displayed it in a completely different way than usual. At first, everything was hung up absolutely normally, but then I was chatting with my sister until midnight, and she categorically refused to leave her home in Dnipro. The next day, after these night conversations, I came to the exhibition hall and rehung all the works to make them seem shifted, with some photographs hanging on the same nail, and another one falling to the floor. It was as if an explosion had happened nearby.

New and best