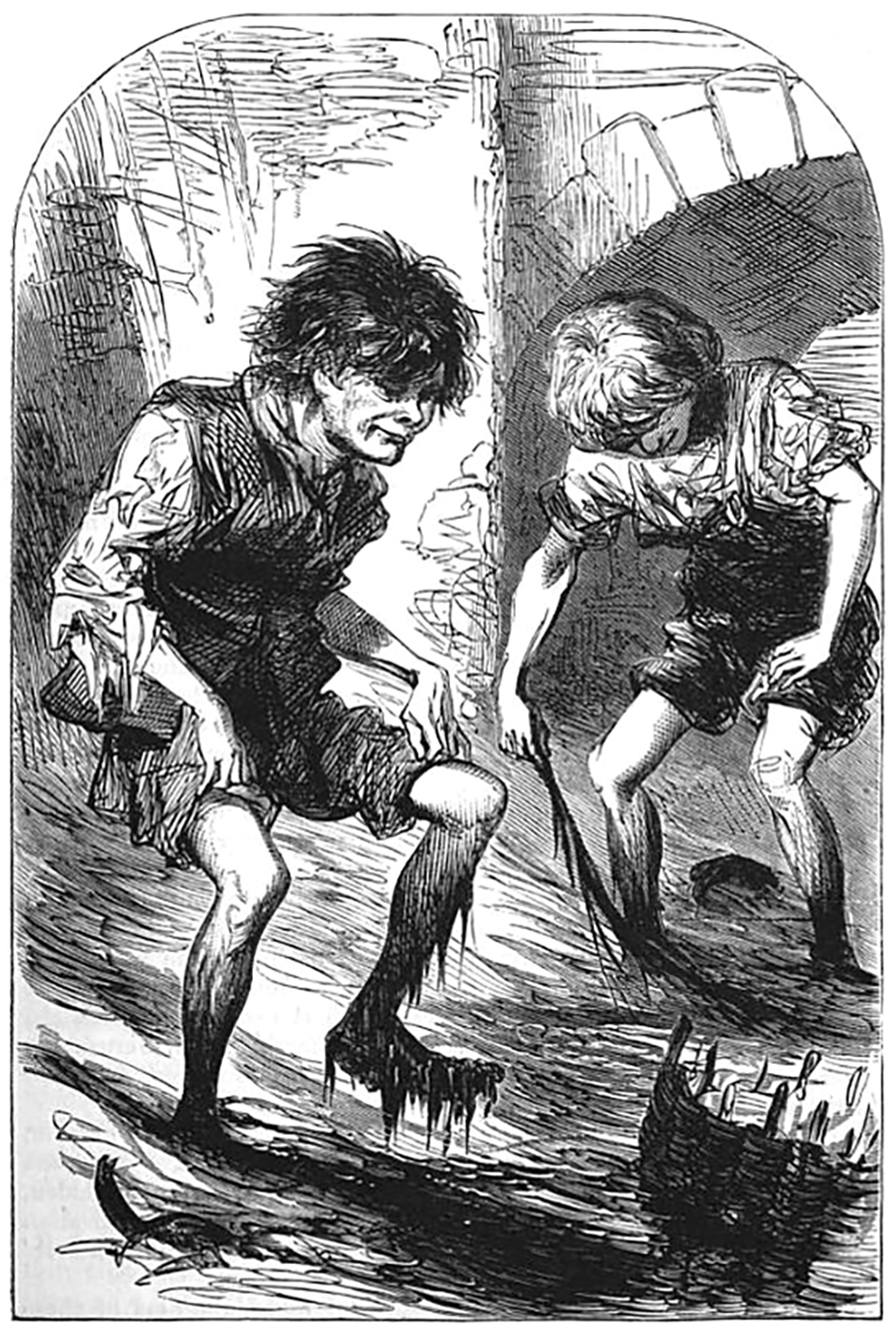

Dirty Business: Who Are Mudlarkers and What Are They Searching for on the Banks of the Thames?

The Thames flows from west to east, cutting London in half, meandering past its modern skyscrapers and ancient docks. Twice a day, thanks to the tide, the water level drops, revealing the history of the British capital in detail. At this moment, mudlarks come out onto the shores.

The term

from the words “mud” – meaning dirt, and “lark” – an activity done for enjoyment or amusement.

In the early 20th century, “mudlarks” were already referring to London schoolchildren who earned pocket money during their summer holidays. The children would ask passersby to toss coins into the mud of the Thames, which they would then scramble to retrieve to the amusement of onlookers.

Today, mudlarking has evolved into a popular hobby for history enthusiasts. In London, there is an entire community of mudlarks. It was established in the late 1970s and was named The Society of Thames Mudlarks. At that time, the city authorities issued nearly fifty permits to enthusiasts for exploring the riverbanks. In 2019, the number of licensed mudlarks was 200, but now there are 5,000 of them. Fearing that active excavations could damage the riverbank, the Port of London Authority (PLA) even halted the issuance of new permits.

Modern mudlarks go on their treasure hunts equipped with shovels, trowels, and metal detectors. Some investigate the surface, some sift through using sieves, and others dig. They most commonly find Roman coins, buttons, jewelry, fragments of ceramic objects, pipe stems, and medieval religious pilgrim badges. These enthusiasts share their discoveries on social media.

Convict's token, 1677. Courtesy of Steve Brooker & Terry Seddon. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Clay pipe bowl in the shape of a slave's head, mid-19th century. Courtesy of Susie White, The National Pipe Archive. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Lead token and stone-carved token mold, approximately 14th to 17th century. Courtesy of Jason Sandy. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Medieval pilgrim badge depicting the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. Courtesy of Tony Thira. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Hand-carved bone gaming pieces, approximately from the 17th century. Courtesy of Jason Sandy. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Cast glass buttons in the Art Deco style, dating from the 1920s to 1940s. Courtesy of Florrie Evans. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Sometimes, objects of archaeological value are discovered on the banks of the Thames. According to PLA, most treasure hunters immediately put up these artifacts for sale, although the law requires reporting such finds to the government or sending them for analysis to the British Museum. Violating this law is severely punished: in 2019, a man who discovered a Viking treasure in the fields of Herefordshire and did not report it to the authorities was sentenced to ten years in prison.

A wide range of people engage in excavations on the banks of the Thames. Today, about half of the diggers are women, although just twenty years ago, they constituted only 5%.

Liked the publication? Support us financially.

Archaeologist Fiona Haughey has been working on the Thames since the early 1990s. She says that while some mudlarkers hope to find valuable items, others are focused on searching for everyday objects from the past that can reveal something about their owner. She calls her technique “beachcombing.” For many years, Haughey has been studying the Banksy area, but she admits that the location never ceases to amaze her. “You can go to the same geographic place, day after day, week after week, year after year, and it is never, ever the same,” says the archaeologist.

Anna Borzello. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Jason Sandy. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Simon Bourne. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Nicola White. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Lucie Commans. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Fran-Joy Sibthorpe. Photo: Hannah Smiles

Motivations for mudlarking vary widely. Some engage in mudlarking to reignite their childhood passion for archaeology, while others do it to take a break from family life and spend some time alone. However, there are also more serious reasons.

“I started doing this to distract myself after the death of a close friend,” says historian Malcolm Russell, author of the book “Mudlarks: Hidden Stories from the River Thames.” “Traditionally the past is presented to us as neat, discreet periods organised chronologically, the product of the biases and interests of those doing the presenting. The jumble of objects that can be found on the foreshore disrupts this. I love letting the serendipity of mudlarking dictate what new stories from the past I discover, finding connections between them, and how these can hopefully give me a better understanding of the present. I also love the simple, raw dopamine hit of just finding stuff,” he adds.

Terry Seddon. Photo: Hannah Smiles

On the cover: Malcolm Russell. All photos: Hannah Smiles

Liked the publication? Support us financially.

New and best