Bird in Flight Prize ’20 Winner Paola Jimenez Quispe: “Photography Is Not Enough To Tell a Complex Story”

Photographer from Lima, Peru, winner of Bird in Flight Prize ’20, member of the jury of the Bird in Flight Prize ‘21. She studied fine arts and communications at Université de Lorraine, France, and currently, she is pursuing a bachelor's degree in photography. Her projects have been exhibited in Peru, Latvia, and Japan.

What have you been doing since November 2020, when you won the Bird in Flight Prize ’20?

I worked a lot on the photobook. I was awarded the Images Vevey Honourable Mention; they are interested in printing my photobook. I also continued to collect material for my next project on sexual abuse within the family. This project has been selected to participate in the Helsinki Photo Festival in Finland.

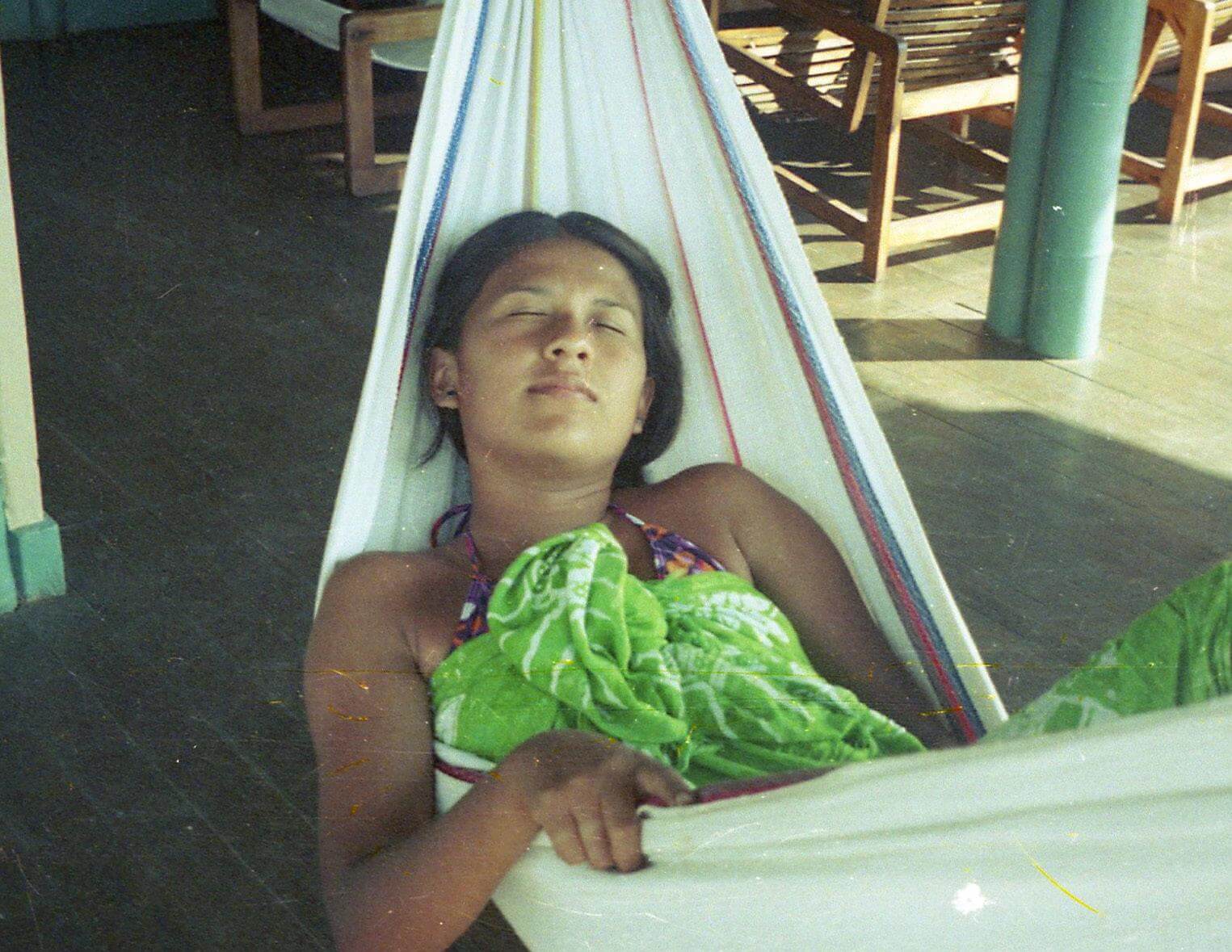

I faced sexual abuse after the death of my father. When I started investigating this topic, I found out that many women from my family have also suffered from domestic sexual abuse – my mother, sister, grandmother, and other relatives. I realized that I like to uncover family secrets. The project is still in progress, but I think I will finish it in a few months. I want to talk to as many women affected by this problem as possible – in Lima and throughout Peru. Doing this kind of work helps me heal.

What media will you use in your new project?

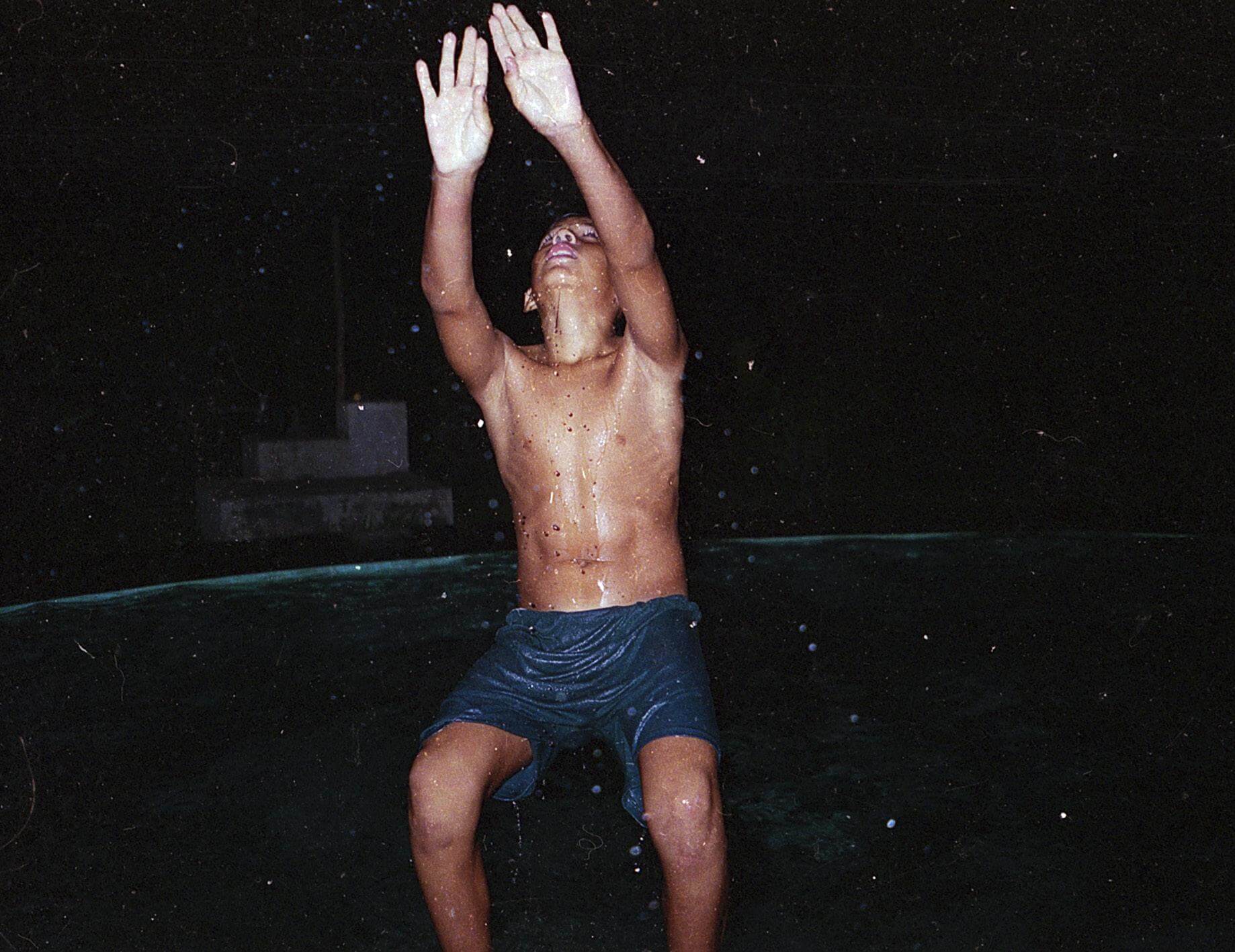

I have realized that photography is great but not enough to tell complex stories. So I take pictures and combine them with text and video. For me, photography is a starting point, but I am also eager to explore other things. For example, I would like to create a website to make collecting stories and sharing them easier.

Many photographers tell me that they have faced a similar problem. We all gradually realize that photography is not enough – both artists and photographic institutions. We can see the increasing usage of the new media in the era of the pandemic.

Is it possible to get a photography education in Latin America?

Peru has one university to get a bachelor’s degree in photography and two technical institutes that teach photography. In addition, there are schools in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Photographers in Mexico receive the most support from the government. The great Ana Casas Broda founded and coordinated the educational program of the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City.

One could say that photography is booming in Latin America right now, but getting a good education in this field is tricky. This profession is still considered somewhat frivolous. Many of my friends studied anthropology, sociology, or communication theory and only then switched to photography.

Earlier this year, I returned to the Peruvian Centro de la Imagen (Image Centre) for my BA. Many famous photographers also studied here.

The Peruvian government does not support artists. There is a community of photographers, which is rather narrow, and it is difficult to get into it if you are not friends with these people. The same authors are exhibited in galleries. This is probably the case in every country in Latin America. However, while working on my projects, I realized that I don’t really need institutions. I can show my work in the media without being famous.

Do Latin American photographers have a style that sets them apart from their European counterparts?

Many renowned photographers from Latin America studied photography in Europe and are guided by European standards. At the same time, local photojournalists are increasingly focusing on indigenous peoples or places where their family comes from (mine, for example, is from Cuzco).

In the past, photographers my age often tried to take one good shot that would be shocking and memorable. But now, more and more attention is paid to storytelling, which is excellent: you cannot cover a complex topic in one shot. Focusing on narrative is the key to creating more exciting projects.

There are still more men than women in the industry. Do you feel any pressure?

Girlfriends of mine who study photography find it challenging to work and study within institutions run by men. Here in Latin America, women face a set of expectations, limitations, and educational prejudices. For example, when I talk about my work, the first reaction is, “Oh, you’re so sensitive.” No one says that I am talented. At the same time, my male photographer friends often hear that their work is excellent, and no one says that they are too sensitive. I often came across this and realized that I don’t have to agree with men.

I am grateful for the photography contests for women, but I ask myself: why should the world of photography be like this? It’s great to create spaces for female photographers to participate, but I think the goal is to make these spaces unnecessary at all. It will take time, but now young women are getting more and more opportunities that we did not have. For example, Isadora Romero and Joyce Alarcon are Magnum Foundation Photography and Social Justice fellows. It’s great, they are really very talented.

Would you recommend more Latin American artists you admire to our readers?

I admire Jorge Panchoaga – he is more of a visual artist, and his work is dedicated to the peoples living in Colombia. The photojournalist from Ayacucho Prin Rodriguez is a truly talented author who creates magical images. There is also Victor Zea, whose recent project is about the hip-hop movement in Peru; Fabiola Cedillo, a photographer from Ecuador who explores motherhood and what it means to be human; Argentinian photographer Violeta Capasso, who studies the lives of young people. There are many great photographers in Latin America, and I am lucky to know many of them personally

Translated by Lubov Borshevsky

New and best