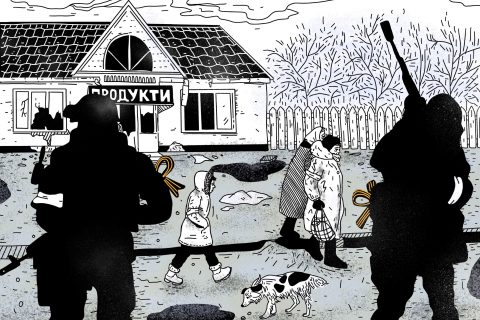

The War That Is Forever with You: Ukrainian Refugees’ Difficulties

According to the UN data, over 4 million Ukrainians had left the country by end-March. Also, at least 6.5 million people became internally-displaced persons, moving to other regions. We have collected stories of five women — three refugees who had to flee the shelling in overcrowded trains and two girls accommodating Ukrainians abroad.

Katia, the Czech Republic

On the morning of the 24th of February, many Ukrainians were perplexed: should they take their mattresses to the corridor behind the load-bearing wall and stay in their flats, go to the metro, or board the train heading West? Katia Shtonda didn’t know what to do either. She wanted to remain with her family, but all her relatives were in Kharkiv, and she was in Kyiv with the food to last a few days and a dog adopted from a shelter.

Some people she knew left at once. Looking out from the window, Katia saw her neighbours take out their suitcases. However, her pleas on Instagram to give her a ride got no response.

“On the fourth day, I decided to go to the metro. I got the dog food, underwear and socks to last a couple of days, a pen, and a copybook,” she recounts. “Near the Druzhby Narodiv stations, I met a girl with a poodle, who taught me how to bring a dog on an escalator: front legs first, then hind legs.”

Katia jokes that she was a godsend. First, the girl asked if Katia was going to leave and then offered to evacuate together before “it gets even scarier, even worse”. Katia didn’t spend that night in the metro and went with her backpack straight to the railway station instead.

The young woman offered to evacuate together before “it gets even scarier, even worse”. Katia didn’t spend that night in the metro and went with her backpack straight to the railway station instead.

“It was one of the worst days in my life: the soldiers near the platform edge were trying to prevent a stampede, then the train came, and people started squeezing me from all sides, squeezing the dog”. The girl with the poodle disappeared into the crowd, and one soldier helped me board the train. “I took his hand and leaned against his chest — it was a beautiful, warm moment, you know. It helped me a lot.”

After 14 hours on the train and a night spent on a down coat in the railcar vestibule, Katia arrived in Lviv. Then he reached Chop, where she boarded the train that delivered humanitarian aid from the Czech Republic and took refugees on its way back.

By end-March, the Czech Republic had given asylum to 270,000 Ukrainian refugees, half of which were children. Ukrainian flags are all over the place in Prague, as well as numerous volunteer headquarters and tents. People are wearing blue-and-yellow ribbons. Hotlines have been working here from day one, with operators speaking Ukrainian and Russian. Also, there are refugee advisory centres all over the country. Public transit is free for refugees. Governmental and private organizations are booking hostels and hotels for Ukrainians as well as setting up accommodations in malls, complete with mattresses, heating, food, and showers. However, people find it hard to stay there for long.

Locals are supportive, too. Many Czechs lend their dwellings to refugees, moving in with relatives or renting less cozy flats themselves for the time being. This is what happened in Katia’s case. “The man who helped me provided a small flat that they rented as an office and moved to the storey below with his employees.”

Prague Main Railway Station, the 7th of March. Photo: Michal Cizek / AFP

Katia was in luck, by the way: a few days after she arrived, Czech PM Petr Fiala announced that the Czech Republic could no longer accept refugees. Those who managed to get in had to check in with the visa centres to get the right to reside for one year in the country. The visa also grants the right to health services and employment. Katia is a producer and plans to stick to her trade. “Production is production wherever you are,” she said.

Katia got lucky, by the way: a few days after she arrived, Czech PM Petr Fiala announced that the Czech Republic could no longer accept refugees.

However, mastery of their language is important to Czechs — even knowing English may not be enough to get a job. It could land you a janitor position but still won’t suffice to work as a nanny.

Now Katia doesn’t flinch as often from the washing machine sounds or sirens of police cars and ambulances driving by, but they still remind her of air-raid alarms and explosions. Also, she says she has nightmares every other night. They are always different but always about the war.

One day, a local Uber driver that hailed from Uzhhorod tried to comfort her: “Don’t worry about Kharkiv — the Russians won’t harm their kin. It’s nationalists who shell it. I watch the news, too, you know.”

Nastia, Hungary

The first family that Nastia Chukovska, who lives in Budapest, took in was from Kharkiv, like her.

“I take their mother by the hand, and she gets noticeably scared, not knowing where I take her. I take them to the supermarket and watch them stand there staring at yoghurts. And they stared for a long time. How long does it take us to look at the products? It’s just a couple of seconds before we take a strawberry one and go on. They stood there looking at it for two minutes, no less. This disorientation when you need to do something this basic… I don’t see relief in that.”

Every week, Nastia greets over 100 refugees at the Budapest-Keleti railway station. She sends us voice messages instead of texts, and there are always city noises and conversations heard in the background — as always, Nastia is accompanying the group of new arrivals. First, she and her husband accommodated the Ukrainians at their place and then went on to create a list of friends ready to do the same. Their acquaintances from the USA and England chimed in soon, offering to book hotel rooms or flats via Airbnb. “One girl from London managed to book an entire hotel near the railway station for a week,” Nastia said. “And my US acquaintance rented several flats, one of them for as long as three weeks.”

Hungary PM Victor Orbán, famous for his rightist views and pro-fascist rhetoric, said that the Hungarian authorities were friendly to Ukrainians. Still, because of his anti-emigration policy, most refugees have nowhere to live. Orbán has been slamming the German and French governments for letting in too many immigrants and thus crippling the foundations of Christianity in Europe. In 2015, Orbán’s Fides party pushed through a number of laws hampering the crossing of the Hungarian border for emigrants moving to other countries, and the PM himself said refugees shouldn’t hope for a good life in Europe. In April, his party won the elections for the fourth time.

Hungary PM Victor Orbán said that the Hungarian authorities were friendly to Ukrainians. Still, because of his anti-immigration policy, most refugees have nowhere to live.

“At best, the authorities accommodate refugees in schools, where they have to sleep on thin mattresses. I still don’t know if you can even have a shower in those schools. On the one hand, there is food and a lot of clothes there. On the other hand, there’s no heating,” Nastia said. “And I don’t really get what the EU is trying to do,” she added. ”I mean, I understand what it promises, but how people are supposed to live before they get decent housing, job, and aid?”

Volunteers give food to Ukrainian refugees at the Budapest railway station on the 1st of March. Photo: Arpad Kurucz / Anadolu Agency via AFP

Nastia calls Hungarian society racist and says Ukrainians don’t enjoy the “white people’s” privileges here. She recounts that Syrian refugees had to live in pedestrian tunnels near the railway station because nobody wanted to take them in. The same thing happens today to students from Ghana and Turkmenistan who fled Kharkiv.

The Hungarian government provides refugees having Ukrainian passports with free railway tickets to Germany, Poland, and Switzerland (however, you still have to pay EUR 3 per seat, and it’s unclear where one can exchange hryvnias for forints). In many ways, this is due to the country positioning itself as a transit space. At least thus far, Nastia knows no Ukrainian who would want to stay — most of them go elsewhere. She heard that it’s primarily people who have Ukrainian relatives in Hungary who stay.

Overall, there is still some capacity and housing on Airbnb in Hungary, but few will be able to actually stay here for long. A whole lot of bureaucratic laws will not let you rent a flat for long in Hungary. Also, the Ukrainians who came to Hungary before the war can’t be granted refugee status, for instance. Besides, local laws hamper mothers with children — the most vulnerable group — if they want to have proper housing instead of a mattress in a school gym. It is prohibited to evict mothers with children from rented housing, and Hungarians are terrified of this law. They refuse to rent out flats to mothers with children for fear of being unable to ask them to leave one day.

Alla, Poland

The most terrifying place where Alla Politaieva has ever found herself in was the commuter train that took her from Kyiv to Lviv. Its passengers spent 12 hours standing in the aisles and vestibules. People on the platform nearly trampled her 11-year-old son. It was physically impossible to get to the toilet in their car, and people had to pee in bottles.

The most terrifying place where Alla Politaieva has ever found herself in was the commuter train that took her from Kyiv to Lviv. Its passengers spent 12 hours standing in the aisles and vestibules.

There are eight border crossing checkpoints on the Ukrainian–Polish border. Rava-Ruska, Krakovets, Shehyni, and Hrushiv are the busiest ones. When Alla was crossing the border, the people who drove there had to spend 10 hours waiting in the queue. The Poles who brought humanitarian aid and took Ukrainians on their way back helped her out.

“We had a backup plan involving a Lviv taxi driver, who could give us a lift to the Hrushiv border crossing for UAH 2,000. He was local and knew a roundabout way through thickets and forests to bring passengers as close as 700 metres to the checkpoint. The rest of the way, we had to walk.”

Ukrainian refugees on the Medyka border crossing in Poland on the 31st of March. Photo: Ayhan Mehmet / Anadolu Agency via AFP

Alla’s friends, who lived in a rented flat, met her in Poland. Problems may arise if you have no contacts in the country: there are many refugees, and the Poles, although hospitable, are afraid to rent out housing for more than three months. Many lessors are worried that the Ukrainians will be unable to pay rent.

Like Hungarians, they are careful about mothers with children: there is a similar regulation in Poland that prohibits their eviction. “My friend was denied rented housing because she has a child,” Alla recounts. “Mind you, her company has moved its office to Warsaw and guarantees solvency of its employees. Her child is 11 years old.”

Alla makes every effort not to rely on Poles’ support more than she should. After all, she has some savings and friends in Poland. The Poles really do a lot for Ukrainian refugees: they hand out free SIM cards at railway stations, set up accommodation and humanitarian aid hubs, and take care of the public transit and health services. The government is developing a law that permits Ukrainians to stay for over 18 months, get a job, study, and get a PLN 300 payout and medical insurance. “The pro-Ukrainian sentiment prevails in Poland,” Alla said. “Locals sympathise with us and feel our pain. Judging by what I heard from old ladies here, they still remember the USSR invasion.”

However, even support of this magnitude can’t bring relief from the survivor’s guilt, a syndrome first documented in former concentration camp prisoners and the reason why Alla can break into tears even after just buying herself coffee. Most often, it’s people who escaped death in a natural disaster, war, or epidemic who suffer from survivor’s guilt. In their eyes, they don’t deserve safety and undisturbed sleep, while others have to shelter from bombings, for example, or have no right to compassion and understanding for leaving their friends and family. Therefore, most refugees who made it to safety feel an acute aversion to enjoying public goods unavailable to those whom they left behind.

“Survivor’s guilt” is a syndrome first documented in former concentration camp prisoners and the reason why Alla can break into tears even after just buying herself coffee.

“The all-consuming feeling of guilt is the strongest feeling I have,” Alla added. “It is stronger than the joy of your child and yourself being safe. I feel shame for almost everything: for leaving almost immediately, for crossing the border quickly, for not spending nights in a hostel, even for being able to work remotely while others can’t. It’s as if someone would feel better if you endured more suffering every step of the way.”

Nastia and Ania, the UK

Photographer Nastia Tikhonova, a London resident, helps Ukrainians find accommodations in the city and tells them how to get a sponsorship or student visa. “On the 14th of March, the British government issued a call for people ready to take in a refugee or even a family. In less than a day, 90,000 applications were submitted on the website, and it even crashed under the load at some point,” the girl said.

Nastia and her boyfriend Mathieu have converted one of their rooms into a bedroom — having passed an inspection, any British resident can provide Ukrainians with accommodations for a minimum period of six months. The government has set up a dedicated platform for this. The Britons who host Ukrainians get a monthly payout of GBP 350 to cover related expenses. The procedure also envisions the Ukrainians getting a sponsorship visa that is different from the refugee status. “It is a better option from the personal freedoms standpoint,” Nastia added.

A rally in support of Ukraine in London on the 24th of February. Photo: Rasid Necati Aslim / Anadolu Agency via AFP

Sitting on a bench near the river in London’s Battersea Park and watching swans, Ania Goldman feels uneasy. Being in a peaceful place like this weirds her out. She doesn’t like being in London supermarkets, where they have everything. Like Alla, she is suffering from survivor’s guilt.

In Ukrainian cities, people queue up near recruitment stations and blood donation centres. Volunteers raise staggering sums in mere hours. Seeing all this, those behind the lines may feel that they don’t do enough, and refugees—that they have outright betrayed their country.

Those behind the lines may feel that they don’t do enough, and refugees — that they have outright betrayed their country.

Ania decided to leave Zaporizhzhia for England, where she has relatives, after Kharkiv came under shelling and saw that she was right to do it after the occupation of the Kyiv Region and the heavy bombing of Mariupol and Kyiv. On day one, the girl thought about heading to Irpin because it seemed unlikely to be attacked by the Russian troops.

To get a three-month visa and qualify for Ukrainian Scheme, she needs to prove that she has relatives in the UK. However, she first had to reach Lviv, where the UK embassy had moved, on a “300% full train”. The embassy was caught by surprise by how many refugees flooded in and announced that it had to move to Poland two days later. “The UK is not only our strategic partner but also the main bureaucratic centre,” Ania said. The girl and her mum spent another three days in the British embassy in Rzeszów — spending 7–8 hours on end there. The procedure kept changing. The papers they filled out became obsolete, and the embassy staff gave them more questionnaires. As a result, they had to go to Warsaw to get the visa, even though nobody could tell them for sure if it was approved. In the Polish capital, they were asked to wait a few more days because the embassy ran out of microplastic and the special paper required for visas.

But it’s over now. Now Ania posts videos from London, showing the quiet cobbled streets, people riding bicycles, and cafes. She said it’s weird being in a country where people spend their time in cafes, and the mattresses are not put in bathrooms. Like many Ukrainians, she feels uneasy falling asleep in safety without expecting air-raid sirens or explosions. “Wherever you go, the war stays with you,“ she said.

Cover photo: Jorge Gil / AP

New and best