I Am Many: Project about the Growing Empire of Migrants by Samuel Gratacap

French photographer Samuel Gratacap currently works in Libya; he made his first project about the displaced people back in 2007 and still carries the theme. Among his awards: the SFR-Le Bal Prize 2013 for young photographic creation, Plat(t)form 2015 special jury mention. Represented by gallery Filles du Calvaire, Paris.

— The first project I did as a photographer was about the migrants living in the detention center near Marseille. I was still a student at the Higher School of Fine Arts in Marseille, I hung out with a collective of the post-situationist artists, documenting their activity and discovering that photography, not painting or sketching, is the most available approach to start working at once.

My interest in the inmates of the center was less about their lives before, but more about how they are maintained, how long they stay inside, what are their rights and the conditions of life, what can they hope for in the future. By all means, it was the most interesting place to work in the city. And that same time, it was on the top of the geopolitical agenda, the main interest of the minister of the interior and the administration of the prefecture.

And that was in 2007, when the minister of the interior was Nicola Sarkozy at full-throttle campaigning to become president, and the administrative process was quite clear: arrest illegal migrants and send them back to their country of origin. They call it 15/15: 15 days of detention, 15 minutes of judgment. No matter who they were and what reasons they had, the juridical system needed no proof, it only had to be effective. When I learned about this, I was shocked as a citizen of France.

Since then I never left the theme, only changed the location: first for Lampedusa in Italy, then for Zarzis in Tunisia. The refugee camps differ a lot, each has its own character and pattern. And even from one visit to another a place changes totally, the people and the stories are never the same. While working on my personal projects I started publishing in the media, mainly in Le Monde.

I arrived in Choucha camp (Tunisia) in 2012, a year after it opened. At first, people were quite open speaking with the media, and I think they believed the media could change something. But when I arrived and introduced myself as a photographer, some of the people were telling me: “Yeah, the others like you came a year ago and we are still here, stuck in the middle of the desert. What are you doing here? What are your politicians doing?”

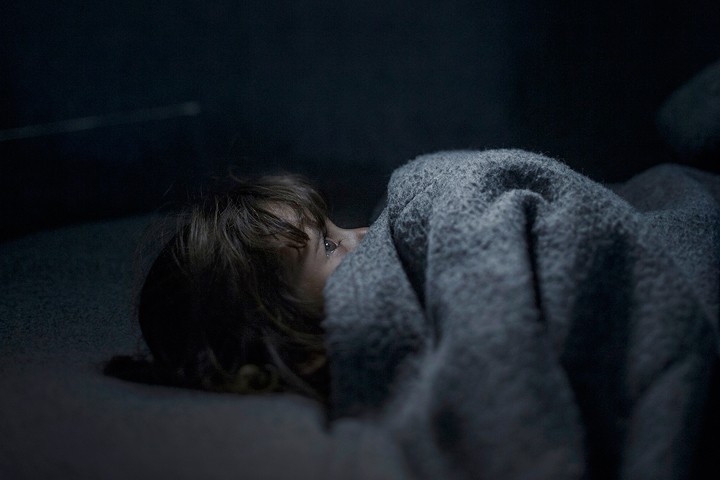

When I just started photographing that place I wasn’t sure what I wanted to show. I had no clue about life inside the camp, how they got food, water, if they worked. I wanted to understand how a human can deal with such circumstances. And so in the first two months, I took very few pictures.

But to understand the waiting of the refugee you needed to stay. It took two years to finish the project, and about a year of it I spent living near the camp on the border of the city.

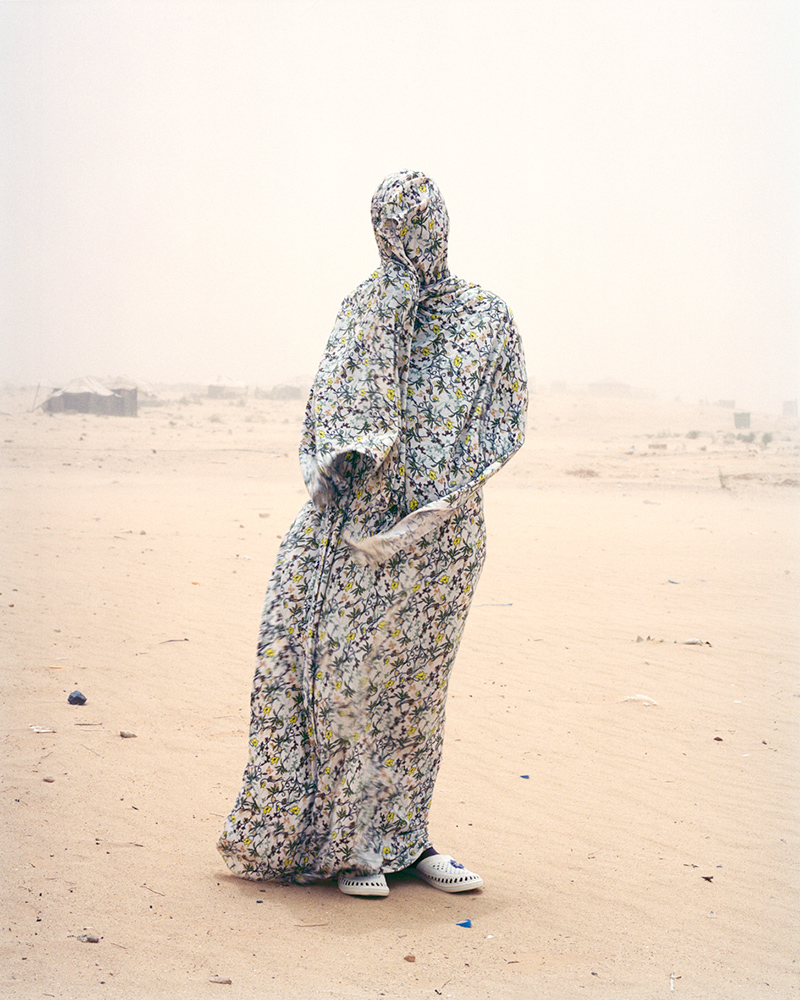

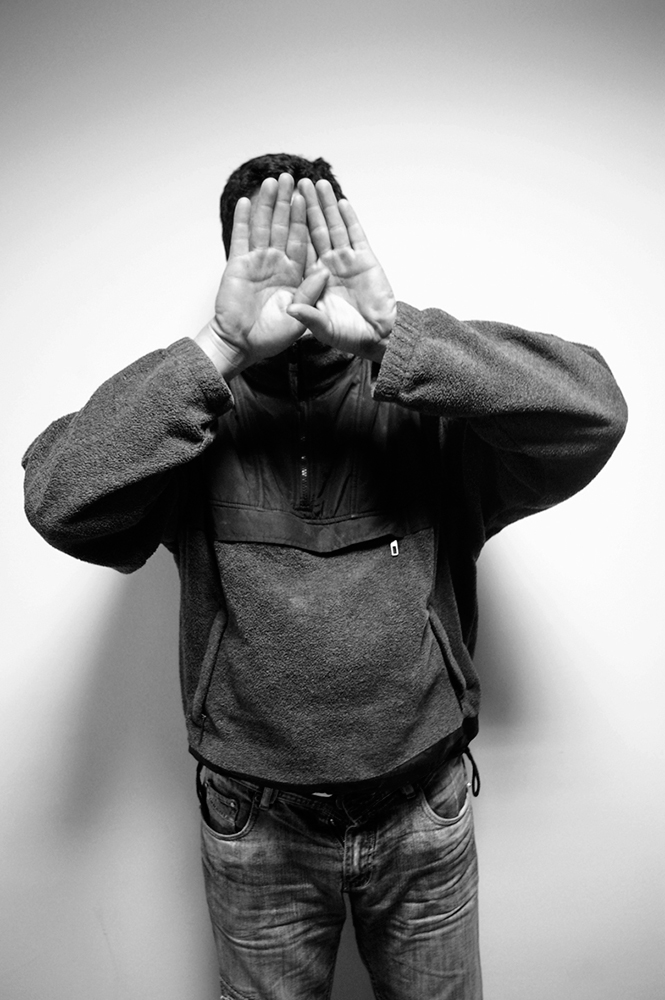

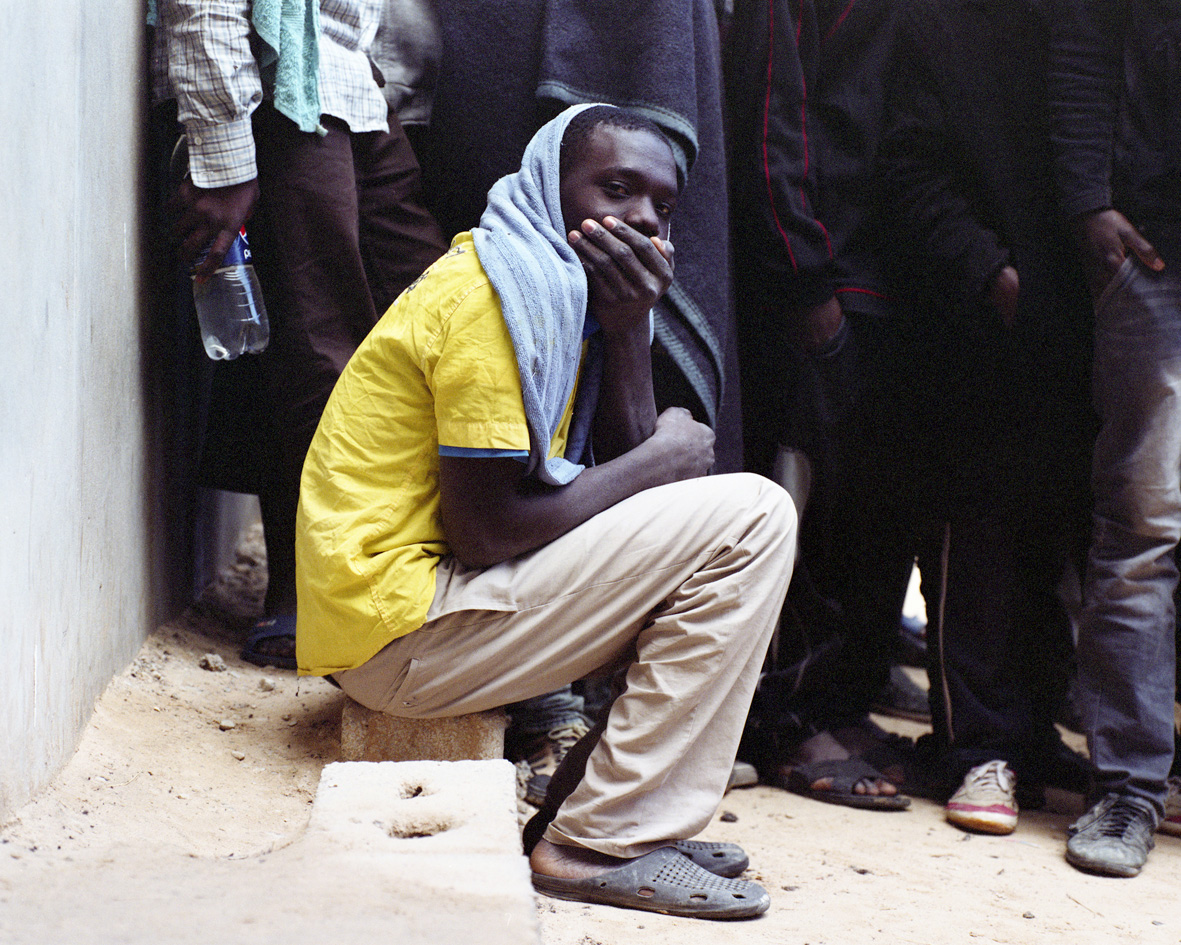

The images of the people with the covered faces were taken during a sandstorm. The wind is never fading there, it damages the tents, carries the sand and it’s everywhere, in the food, inside the tents and the clothes. They were taken not long before the official closure of the camp in 2013. The closer it was to the moment the harder it was to work, because I needed a reason to stay there as a photographer, it’s a military area after all. Thanks to the photography workshop for teens I was teaching for a Danish NGO I could participate in the local social life and get authorization to stay inside.

Not all of the people get financial support from the NGOs and even if they do, this money is not enough. People have to go to the closest city and try to find a job, illegally of course, and that is 25 kilometers away. The same is with the food, it is not enough. And it’s often like they give you pasta and you are Sudanese and you don’t eat pasta.

And actually what I saw and what I think also happens in other places is that the appearance of the camp bursts the economy of the area because thousands of people come with the need of things and with the offer of labor. And it doesn’t matter if they are legal or not, they are looking for a solution.

The period of the functioning of the transit camp depends on the time needed to resettle the asylum seekers. At first, a refugee applies for the status of asylum seeker. If he is rejected he can make an appeal, but it doesn’t work in most cases. If a refugee is granted a status of asylum seeker then he can apply for resettlement to another country and all is left for him is to wait for the hosting country to accept him.

The people I met in Choucha were mostly from Sub-Saharan countries and Palestine, Iraq, Bangladesh, Pakistan, who flee from the war launched by the countries with the greatest interest in the resources of those territories. The same countries that bombed their houses and made them refugees later came with humanitarian aid and started judging, dividing, and discriminating. That is the empire and the people I met are its victims. The system managed to divide the people even inside the camp, designing sectors depending on their status and the nationality. This was again a projection of the empire and its properties.

In the case of Choucha, the answer about what I was doing there came quite unexpectedly. I finished the project and it was on exhibition when the body of Alan Kurdi was found on the seashore in Turkey. Suddenly, the destiny of the refugees got a lot of attention in the media. And the dramatic events in Turkey touched even the exposition of the Empire project. I got an opportunity to speak about life in the camp and about the fact that even after it was closed, many people stayed there for they had nowhere else to go.

As a photographer that is all I can expect and hope for — to reveal the story. After all, in 10 years doing photography, I’m going deeply after the theme as it is not the next project for me, not a personal something, it is the universal story of human beings.

New and best