Honoring the Ancestors: The Voodoo Cult in Modern Benin

Voodoo is a fusion of religious practices of several African ethnic groups, including the Yoruba from Nigeria, the Fon tribe of Benin, and the Ewe people of Togo. Therefore, it takes on different characteristics and emphases when practiced in various locations. Voodoo first came to the United States, Brazil, and the Caribbean in the 17th century, along with the slave trader ships; it later became widespread in South and North America.

In 2020, Paola Chapdelaine came to Benin to carry out her first photo reportage about a local waste recycling project founded by her friend, whose family practices Voodoo like many people living in that area. This piqued Paola’s interest, and she ended up exploring the local Voodoo culture via photographs.

A French photographer specializing in art, reportage, and documentary photography. She is a part of the Hans Lucas agency and has two honorable mentions at the Paris Photography Prize PX3.

— Having lived her whole life in France, my friend Naomi has a deep wish to reconnect with her African heritage, which primarily involves the Voodoo religion and, more specifically, the cult of ancestors. The Voodoo religion, which can translate into different cults depending on the families or locations where it is practiced, is present in every aspect of life in Benin.

While living in Porto Novo, I was often awakened by the sounds of Zangbeto, the traditional voodoo “guardians of the night” – a group of young men involved in patrolling the streets after midnight. Those things were casual. I ended up splitting my time between working on the reportage for Naomi’s association and exploring her cult.

Most of the inhabitants of Benin are descendants of Africans not deported to the Americas; the minority, however, are descendants of freed slaves that came back to Benin around the 19th century. Upon their return, they readopted Voodoo cults as a form of opposition to white Catholicism. In contrast, many of the returning Afro-Brazilians in Togo turned their backs to Voodoo in an effort to gain social status in the eyes of colonial powers.

Voodoo cults are part of the local cultural heritage and a form of opposition to white Catholicism.

Matthias, a Voodoo priest, spends time with his niece before the ceremony

Matthias communicates with the other world with the help of a rosary

The altars of Legba - one of the main deities of the voodoo religion, acting as a mediator between the world of spirits and the world of mortals

Today, centuries later, the link between the country’s past of slavery and Voodoo is no longer apparent in daily religious practices. The Western culture branded Voodoo and the cult of ancestors as an obscure ancient practice; it was often portrayed as more traditional and thus less “noble,” less legitimate than other more widespread religions.

For instance, Voodoo indeed involves animal sacrifices, but I’d be curious to know how this “barbaric” rite differs from even more monstrous European traditions. To understand another culture, you need to discard stereotypes and live the lives of people who have known this culture from childhood. This is what I did.

I was lucky to be perceived as a guest rather than an outsider, as my host’s family has great authority in the communities of Benin. Moreover, Naomi is determined to make her religion better known and deconstruct prejudices about it. I certainly benefited from her facilitation in the places we visited and with the people we met.

Within the cult of ancestors, all the crucial decisions are being consulted through the Fa, which is a means of communication with the gods and ancestors. The Bokonon (priest of the Fa) is the highest qualified person to receive guidance from the ancestors and divinities. Based on their communication, he can predict the future. Therefore, when facing a challenging time or a significant choice, people ask to consult the Fa in order to receive guidance. Before a consultation, they whisper their questions onto a money bill and keep it close to them for about two days. During the consultation, the bill is placed by the Bokonon amongst other ritual items.

To consult the Fa, the Bokonon uses a rosary made of nutshells. It is gently thrown to the ground to reveal a specific combination. Then, repeating this step a couple of times, he recites prayers, usually in the Yoruba language (Voodoo’s origins come from Nigeria, where Yoruba is the primary local language). Then, through a series of fables, the person’s questions are answered sometimes in a metaphoric way, sometimes more concretely with specific advice. Here’s a fun fact: when I consulted the Fa myself, asking about the journey I wanted to take on as a photographer, I was told I would succeed, but also advised to read my contracts very carefully!

An ancestor’s spirit whirling in a dance

The cult leader speaks quietly to an ancestor. He holds a stick in his hands to keep the spirit from getting too close to the audience

The whole family gathers for the ceremony. In Benin, “family” is usually understood as a community of extended family living in the neighborhood

One of the ancestors’ spirits

Musicians perform at the ceremony. Their drums set the beat for the dance of the ancestors

A major role of the Bokonon is to identify areas that may challenge you, and the animal sacrifice is meant to clear the way forward. For this purpose, he drafts a list of ingredients that you must buy for him to carry out the sacrifice. The ceremony usually requires one or two birds, palm oil, a liquor made from palm wine, beer, and nuts. After the ceremony, the birds are eaten at a family dinner along with liquor and beer. The more serious your question, the more sacrifice the Bokonon will have to make.

The sacrifice usually requires one or two birds, palm oil, a liquor made from palm wine, beer, and nuts.

When significant events happen (a wedding, childbirth, etc.), the ancestors are called to come back as revenants during a ceremony attended by the whole family. It must be understood that “family” refers to an entire neighborhood: several house units forming a family compound. During the ceremony, revenants carry out dance demonstrations accompanied by drums. Young men initiated to the cult hold a mediator role between the attendants and ancestors, as it is considered that the spirits may start becoming somewhat violent. Revenants may spontaneously address different people from the family to congratulate them or, on the contrary, to pinpoint poor behavior.

After the first ritual I took part in, Leopold, who is a Gballey (cult leader), was kind enough to answer my questions. Leopold can consult the Fa just like the Bokonon, but he is mainly involved in the oversight of the community and events taking place. During my conversation with Leopold, I was trying to give structure to his explanation about the relationship between the different divinities and the family ancestors. Instinctively, my mind had wanted to create a hierarchy, and quickly I was reminded that this thought process was very much Western. The relations I was trying to grasp were actually much more horizontal. This example stuck with me, and it shows that a majority of our world views are a byproduct of the society we live in.

Gin for the sacrifice ceremony

A rooster and a hen for the sacrifice

After the ceremony, the birds will be used to prepare lunch for the whole family

Leopold, head of the family and leader of the ancestor cult

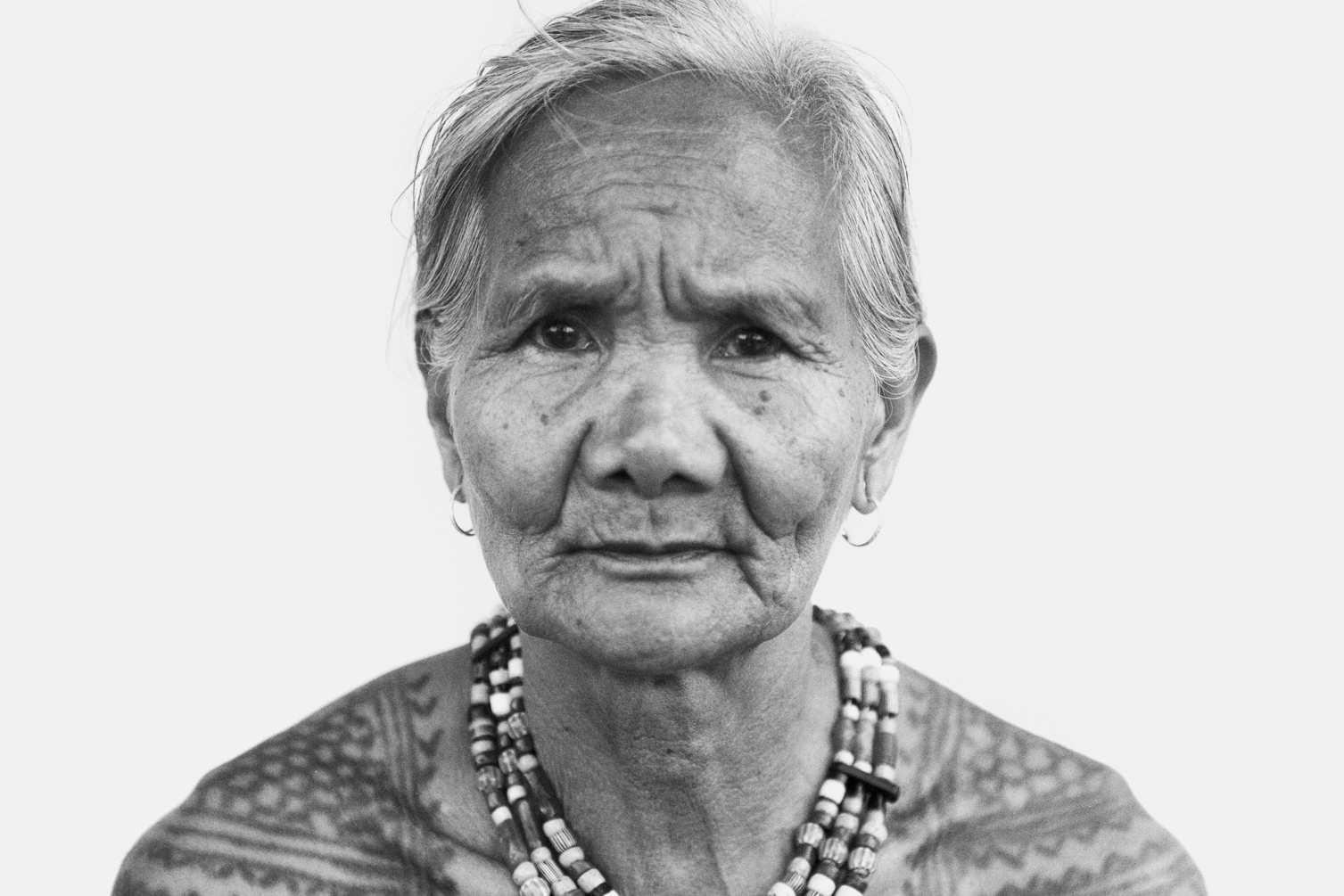

Nevertheless, the Western lifestyle is spreading fast in Africa. In this culture, the elderly family members have been traditionally revered, sometimes even feared. They carry a crucial role in the lives of the youth and are considered the wisest of all family members. In contrast, the way the Western world attends to its elderly people is the complete opposite of how generational kinship works in Benin and other non-Western countries. However, due to African societies becoming more Western-oriented, older people tend to live more and more alone, whereas traditionally, they would be taken in charge by their immediate families. One can thus imagine how the cult of ancestors enables the maintenance of strong bonds between generations, passing on important values and history.

In any documentary project, little is more important than showing genuine, deep empathy. This means taking enough time to study and understand the context and challenge your own framework and set of values. Remember that what you experience is never a show; these are lives of real communities, legitimate as any other – including our own.

What you experience is never a show; these are lives of real communities.

Our whole worldview is based on upbringing, on context-specific teachings. I find it extremely cringeworthy when a different culture is (dis)qualified as being bizarre. My message is to try as much as possible to deconstruct one’s preconceived ideas, and in those instances, to listen more than to speak.

Due to pandemic restrictions, ceremonies are not allowed on the streets. Instead, they are arranged in the courtyards of houses. A group of young people climbed onto nearby rooftops to watch the ceremony.

Translated by Lubov Borshevsky

New and best