Delete After Viewing: An Intimate Diary of Someone Else’s Life

Beauty standards have always been determined by culture and the role society attributed to women. Paleolithic Venuses with hypertrophied parts of the body associated with fertility and childbearing emphasized the role of women as nurturers and life-givers. The obesity of the Iranian women of the Qajar era indicated prosperity and high social status. For Japanese women, whiteness and skin pallor were especially important as a marker of high socioeconomic level.

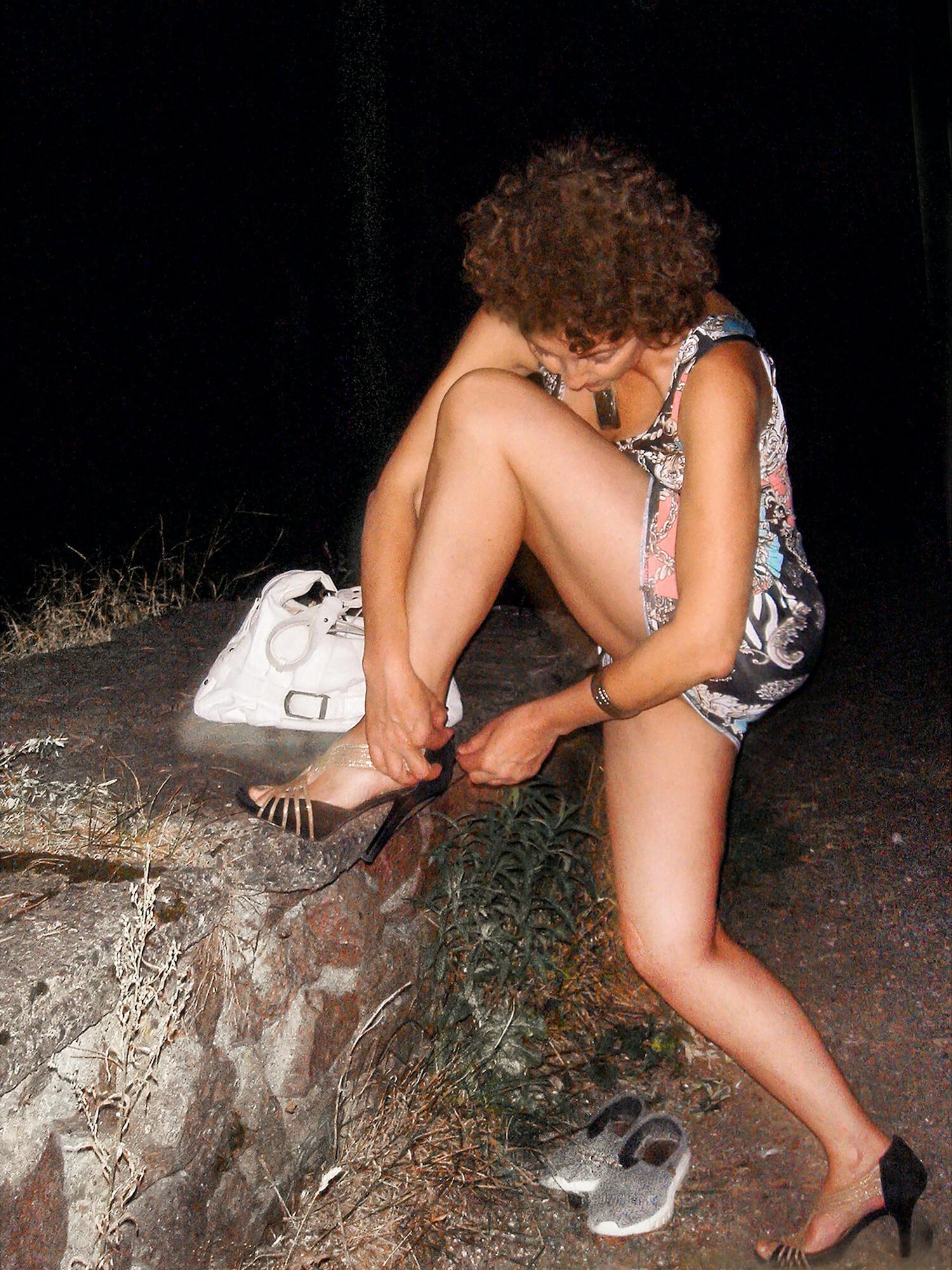

Nowadays, the female body is still under the spell of censorship and imposed standards, be it an art project or a picture published in a magazine or on social media. But Olga Kirillova believes that a naked body cannot be ugly when photographed honestly and sensually. Ignoring negative comments, she continues to fill her friend’s “secret folder” with her own erotic photographs. This project is not just about her deceased friend; it is also about accepting her own body and sexuality and simply appreciating life.

An artist, photographer, and pianist based in Minsk. Olga graduated from the Belarusian State Academy of Music. She works with photography, video, and performance. Her artworks were published in the Belarusian cultural media (“Mastatstva,” “Kultura,” “Bolshoi”) and nominated for the Bird in Flight Prize (special Panasonic Readers' Choice Award). In addition, the photographer has participated in art exhibitions in Belarus and Latvia.

– Shortly before her death, my friend asked me to revise her digital archive and delete all the nude pictures after her death. She herself could no longer do it. Or, perhaps, she did not want to remove them before the “deadline,” as if killing herself ahead of time. Her request sounded like a desire to hide her private life from prying eyes, but I also sensed remorse and regret.

We knew each other from school, studied at the same university, knew each other’s families, went to visit each other, traveled, did theatrical and humorous projects together – that is, we were pretty close. After university, we moved a little away from each other due to work and family life but continued seeing each other regularly – the school friendship is the most memorable.

She was incredibly cheerful, artistic, and graceful – I always knew that. The folder’s contents, which she shared with me shortly before her death, completely coincided with this image. At the same time, it is a challenge and a responsibility to become a witness to what was not initially intended for you. I understood that I got access to the archive not because of our friendship but because I was engaged in photography. “You know what to do with it,” the friend said. At first, I experienced awkwardness, a mixture of shame and curiosity, and a mild degree of voyeurism. I later recognized the project’s photographic potential.

I experienced awkwardness, a mixture of shame and curiosity, and a mild degree of voyeurism.

It was not the scenes of the pictures from the secret folder that struck me, but their uninvented beauty. What surprised me was not that my friend had lovers but how meticulously she recorded and collected evidence of love affairs. I thought that this was a habit of a later time and a younger generation: taking endless selfies on the phone for social networks. But filming each other almost blindly with the first digital cameras… what for? I felt this was a “hymn to freedom and emancipation” (as one Belarusian critic would later write about my project). Finally, I realized that archiving was her way of experiencing and maintaining happiness, and I knew that these pictures should not disappear.

What surprised me was not that my friend had lovers but how meticulously she recorded and collected evidence of love affairs.

All photographs were taken at a fairly mature age. My friend was about 50 years old, and the filming period covered about a decade before her illness. The pictures were stored in several folders and arranged over the years. The nude images were not “on the surface” – sometimes, they were denoted by special marks or had a different format. I also found a separate folder with texts of SMS messages from an old phone. They, too, were kind of classified, hidden among metadata, dates, and numbers.

The archive turned out to be very large. She had been photographed a lot. There very also numerous self-portraits – creative, sensual, and charming. Those “shameful” photographs were breathtaking scenes from her personal life.

Fulfilling her will, I deleted all the files, but I could not allow them to disappear altogether. I repeated the scenes filming myself instead of her; I appropriated these images, becoming both a witness and an accomplice. She got an additional, invented life.

I found the cameras she used to shoot with; I went shopping searching for clothes like hers; I tried to reproduce the surrounding entourage and landscapes seen in her photographs. I asked men to pose and take pictures of me. Unfortunately, not everyone close to me understood me, which became a reason for breaking off some relations.

I searched for clothes like hers; I tried to reproduce the surrounding entourage and landscapes seen in her photographs.

The strangest and most important episode for me was a chance meeting with the hero of her story. After sharing my staged pictures with him, I learned that he also had these candid photographs but deleted them. “For me, this is not just a story of meetings and dates; this is a world of change in the two of us,” he said. So now, these images exist only in my version. And if before I had any doubts about ethical issues, they disappeared after talking to the hero of this very personal archive.

Not a day went by that I didn’t think about my friend. But the more I got involved in the project, the more it became about me. Her story turned into my own.

Some photographs can’t be distinguished from the original at a glance: we are like twins. At some point, this story ceases to be about one secret personal life, turning into something familiar to all of us, and therefore normal and natural.

I have always believed that there is nothing more beautiful than nudity. However, the body for me is not a sculpture, not an aesthetic category; it is an expression of desire, strength, courage; a combination of emotions and gestures. This is common for any age, gender, and body size. But what seemed to me an expression of beauty and freedom looked vulgar and sick in the eyes of others.

My boyfriend looked at me with suspicion, and I started hearing dirty words – first as a joke, then seriously. Finally, I was advised to see a doctor.

What seemed to me an expression of beauty and freedom looked vulgar and sick in the eyes of others.

Most often, I heard something like “this is not appropriate for a decent woman your age” or “privacy is inviolable.” Once I was criticized for looking too good for my age: I was told that the project would be relevant only if I were unattractive or unhappy. This attitude is not necessarily related to patriarchal views; issues of aesthetics and ethics depend on the market. The boundaries between what is “permissible” erotica and what is porn excluded from the realm of art are determined by a temporarily elected government.

The naked body is primarily associated with sexuality, sexuality – with uncontrollable emotions, uncontrollability – with danger. Therefore, sex is dangerous. But I see no reason to hide myself. On the contrary, I protest, opposing fear and lies. After all, I am a musician and have always loved the stage.

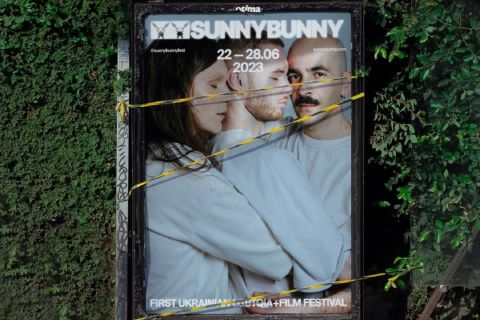

I am close to the position of the Ukrainian artist Sasha Kurmaz, who released a photobook called “Lust,” which contains amateur erotic pictures from the network. This is a great artistic study and, I would say, rehabilitation and, in some way, legalization of sexual photography.

Thanks to the archive and the project, I learned new things and accepted my hidden parts. The archive was the starting point, the reason to revise the shooting process. I found my own style, based on documentary and amateur photography, where the focus shifts from the artist (who is anonymous, dissolved) to the topic. Photographing has become an act of fixing life, an attempt to resist fear and death.

Anyone can do what I did because everyone takes pictures nowadays. But not everyone would show this truth, this other side. I insist on the possibility of showing the complete picture; I don’t want to hide those parts that are less comfortable to look at. I consider biography, private and public life a creative field, and the body an instrument. In this sense, I believe myself to be engaged in performative practices. If something exists, it has the right to be seen and heard. And watching is a personal matter.

I consider biography, private and public life a creative field, and the body an instrument.

I am already older than my friend was. I want to be in peace with my body, desires, losses; I want to appreciate my life. Otherwise, I risk being held captive by false shame, fear, guilt, and betraying myself and my life by “destroying the photographs.” So what can I do to rise to this challenge? I look fearlessly into the camera lens, I smile openly, and I love desperately.

Translated by Lubov Borshevsky