Claustrophobic Vision: Ilya Kabakov, Child Illustrator for Adults

Ilya Kabakov was born in the Soviet Dnipropetrovsk in 1933. At the age of eight, he moved to Moscow, where he later graduated from an art school and institute. According to Kabakov, even from his youth, he didn’t trust everything that the Soviet system, particularly education, offered. However, he had to adapt and learn to lead a double life: “I accepted the Soviet reality as the weather, it was a given. If you live in a country where it always rains, you can’t hope to fight the rain by organizing demonstrations.”

A conformist and an adapter—this is how Kabakov described himself. In the artist’s opinion, he embodied cowardice. Despite his genuine hatred and disdain for everything Soviet, the artist never actively opposed it.

Conformist and adapter—those were the terms Ilya Kabakov used to describe himself.

Becoming a children’s book illustrator was a safe haven for Kabakov, the only profession in which he could engage without compromising his conscience. It served as his peculiar alibi: during working hours, the artist created illustrations for children, while in his free time, he produced works for adults. In the underground art scene, Kabakov prepared what he called “albums”—collections of drawings and texts that metaphorically criticized the existing order. These albums were only revealed and shared with like-minded individuals during clandestine gatherings held in the artist’s apartment.

Kabakov was able to emerge from the underground only after emigrating from the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, at the age of fifty-five, the artist left the USSR. He settled in New York, specifically on Long Island, where he lived and worked until the end of his life. In 1989, he married, and his wife Emilia later became his collaborator and co-author.

Together, the artists began creating installations that served as three-dimensional embodiments of Kabakov’s underground graphic drawings. The couple referred to their works as “total installations” due to their grand scale and all-encompassing nature.

Each installation is accompanied by a textual narrative and can represent a separate space, such as a room or even a building. Such an art object engulfs the viewer. Typically dimly lit, claustrophobic, depressive, and overloaded with details, the installations mimic interiors of Soviet times: communal apartment rooms, school classrooms, bureaucratic institution corridors, or toilets. They resemble film or theater set designs, but without any characters. The Kabakovs’ idea was that the viewer becomes the protagonist of the installation. They are not passive but rather animate the space. Without the viewer, the installation loses its meaning.

Poorly lit, claustrophobic, depressive, and laden with details, the installations emulate interiors of Soviet times.

The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment

Communal apartment – a phenomenon that occupies a central place in Kabakov’s practice. The artist views the communal living space as the quintessence of Soviet life, a space where the incompatible coexisted – collective and personal: “The communal apartment is a successful metaphor for Soviet life because it is impossible to live in it, but it is also impossible to live differently because leaving the communal apartment is almost unreal.”

The most famous total installations by Kabakov are dedicated precisely to communal life. “The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment,” created in 1985, is one of the most iconic and poignant works by Kabakov. The installation simulates a cramped room in a communal apartment, its walls densely covered with political propaganda posters. Instead of a bed, there is a dreadful folding bed, and a pair of old shoes replaces clothing; that’s all that remains of the imaginary inhabitant of this space. In the middle of the room, there is a strange structure resembling equipment for bungee jumping, with a hole broken in the ceiling above it, as if someone has swiftly flown through it. It turns out that the only way to escape the communal apartment and the USSR, found by the imaginary protagonist, is to catapult oneself into space, thereby realizing the Soviet dream of exploring new planets.

This work is like a metaphor for the artist’s life, who spent most of his time tied in the confines of Soviet life and yearned to leave it to enter the Western art world: “My mentality is Soviet, my place of birth is Ukraine, my parents are Jewish, my education and language are Russian. I dreamt of becoming part of European culture, a dream that remained practically unattainable for the majority of my life.”

Throughout his career, Kabakov created paintings, often monumental in size. Fragments of his canvases evoke Soviet painting, works from the 17th century, avant-garde elements, and personal memories. Like fragments of memory, they layer upon one another.

“My mentality is Soviet, my place of birth is Ukraine, my parents are Jewish, my education and language are Russian.”

The paintings are the most commercially successful part of the artist’s oeuvre, with some of them fetching millions of dollars. However, Kabakov excelled the most in his installations. Installed in museums in the US and Europe, they serve as a teleportation device to the Soviet world for viewers with different mentalities, histories, and cultures.

School No. 6

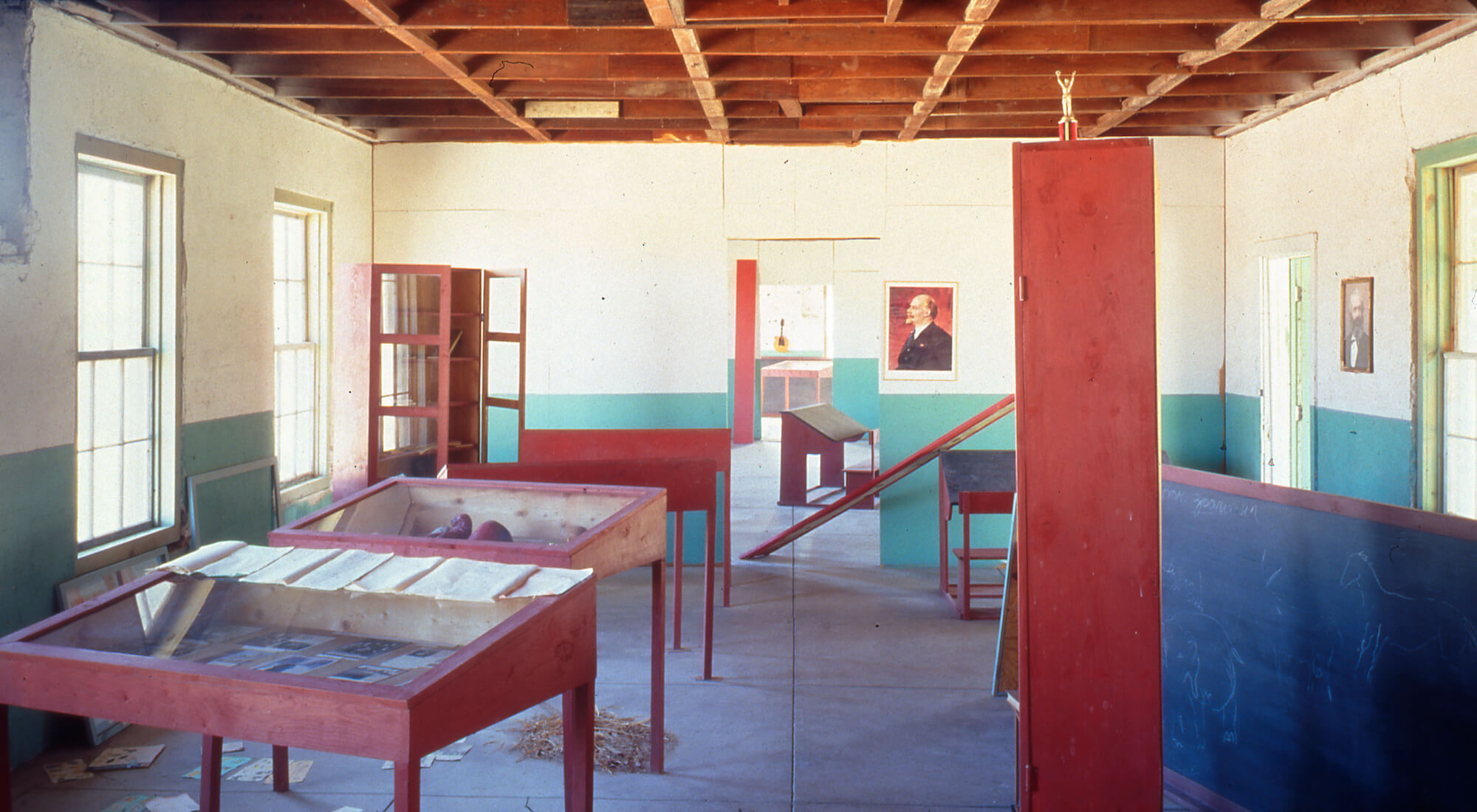

One such installation is “School No. 6” created by Kabakov in 1993 for the Chinati Foundation, a contemporary art museum in Marfa, Texas. The invitation to construct a permanent installation came from the founder and ideologue of the museum, renowned minimalist artist Donald Judd.

Amidst the collection of minimalist sculptures in the Texas desert, the model of an old Soviet school appears quite exotic. The installation occupies an entire building, weathered and worn on the outside and inside. Everything here is abandoned and dilapidated: the courtyard overgrown with weeds, the classrooms furnished with typical Soviet desks, yellowed lesson schedules and portraits of Lenin on the walls, scattered books on the floor. These items were brought by the Kabakovs from the former USSR. The school represents an instrument of the Soviet state. Following the artist’s instructions, any form of maintenance or repair of the building is strictly prohibited. He regarded this object as a landmark and artifact of the Soviet regime, destined to self-destruct over time.

A permanent installation representing a Soviet school. Created by the artist for the Chinati Foundation, a contemporary art museum in Marfa, Texas. Photo: Florian Holzherr, Chinati Foundation.

The Red Pavilion

In 1993, while representing Russia at the Venice Biennale, the Kabakovs created an installation that is a miniature replica of the existing Soviet Pavilion in Venice. In terms of size, their structure resembles a small shed, emphasizing its pitiful nature. However, it is solemnly adorned with all the important attributes of the Soviet era: the sickle and hammer, the red star, flags, and festive slogans grace the pink building.

To see the Red Pavilion, visitors had to navigate through a maze of planks and construction materials. Created shortly after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this installation served as a reminder that the Soviet regime had not disappeared but rather lurked in the shadows.

Created shortly after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this installation served as a reminder that the Soviet regime had not disappeared but rather lurked in the shadows.

Other installations by Kabakov, installed in museums around the world, have also become monuments to the dangerous state hidden behind the mask of modernity. “The Red Pavilion has returned,” said Emilia Kabakov in one of her recent interviews, referring to contemporary Russia.

New and best