Life in Yemen: A Country Amidst War

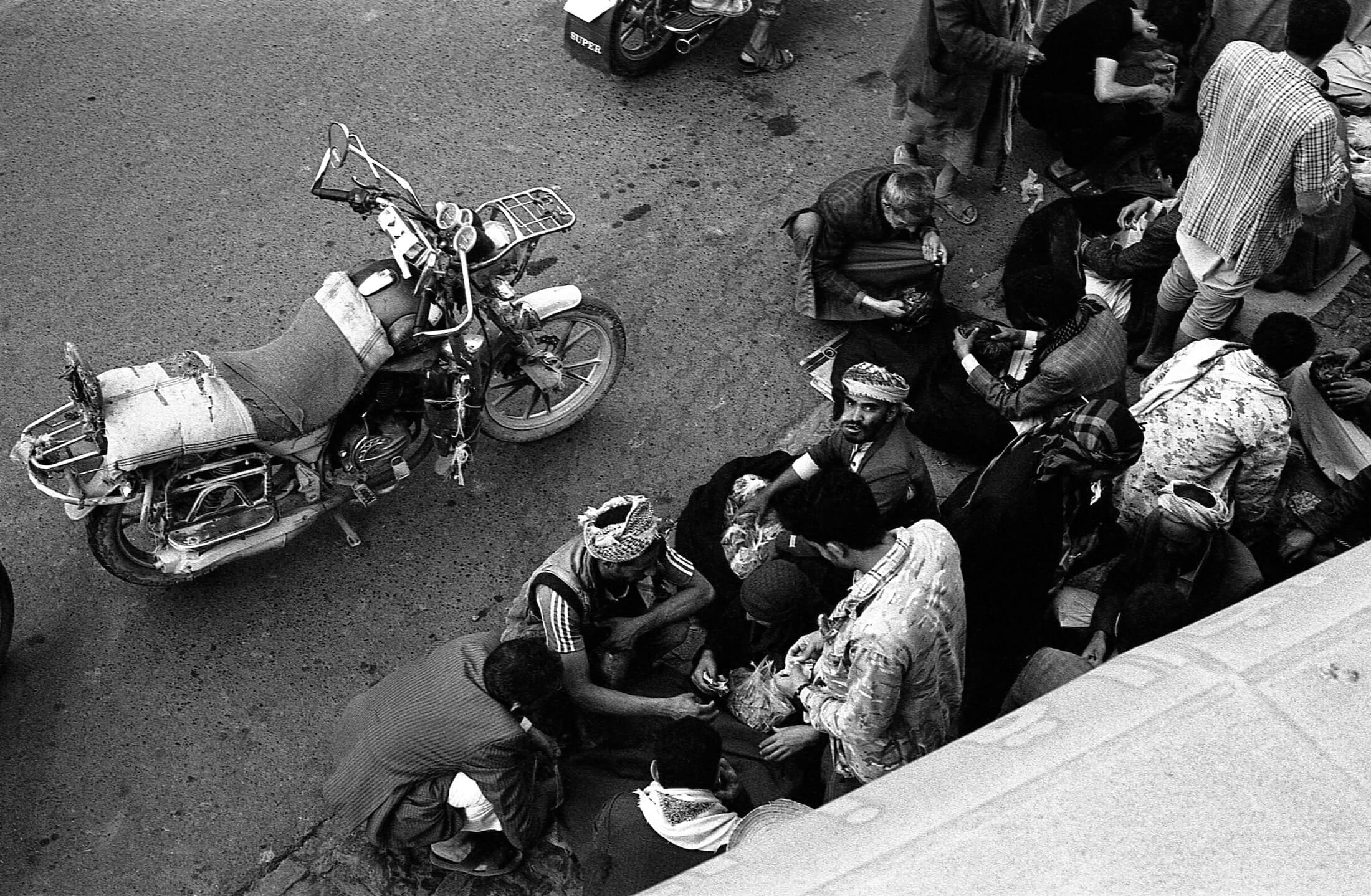

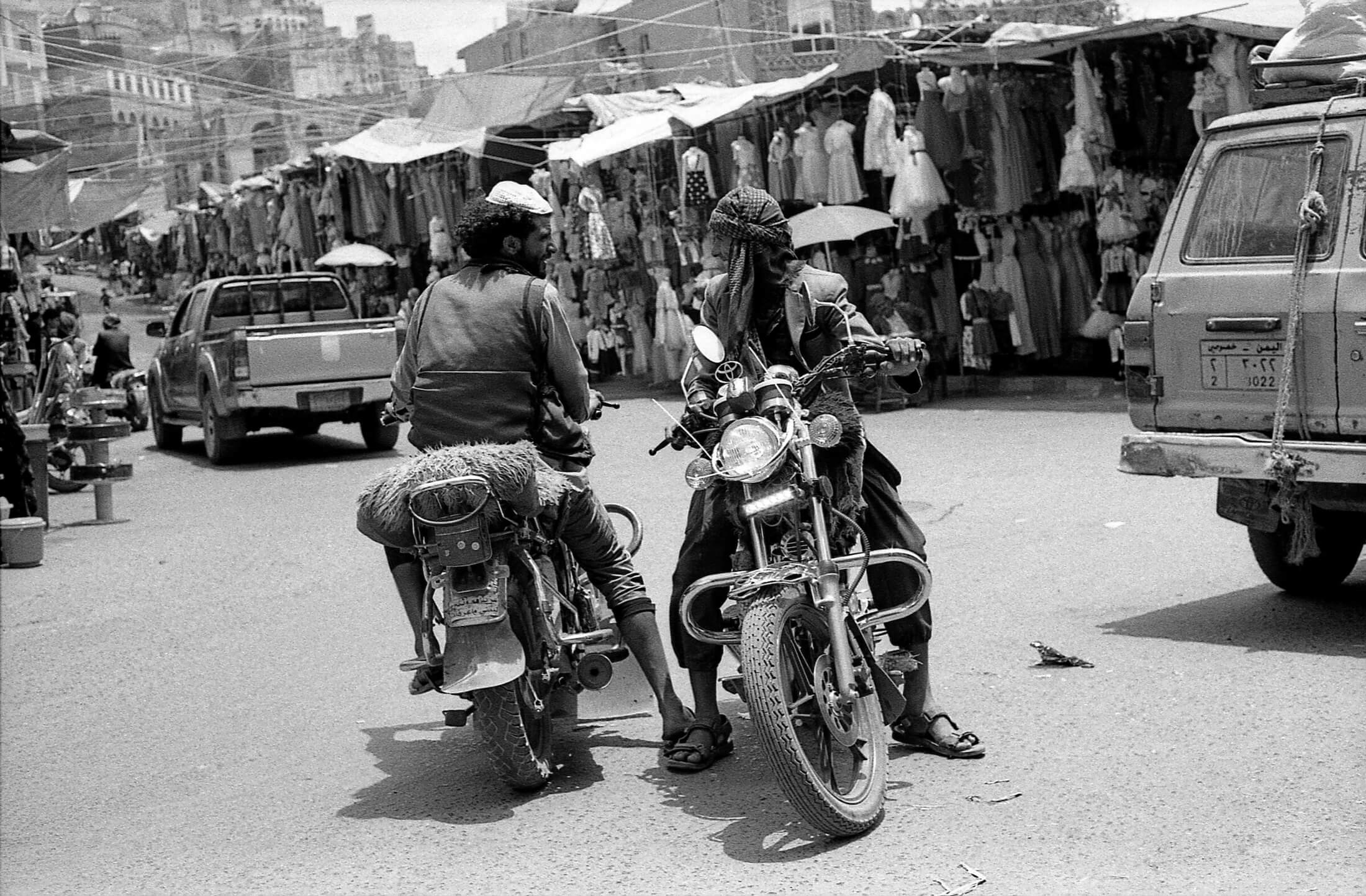

The majority of photographs from Yemen focus on the realities of the civil war that has been ongoing since 2015. In contrast, Francis documents its beauty and everyday life of the locals. In his project “Felix,” he offers a fresh perspective on a country that is often depicted solely through the lens of conflict.

Based in the United Kingdom, Will Francis is a photographer with an academic background in mediaeval Middle Eastern literature. During his time in Cairo, where he was living and studying, he fortuitously discovered a historic darkroom situated in the heart of the city, which sparked his interest in photography.

— Although I had been privileged and fortunate enough to travel and photograph widely, including in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan, I was drawn to Yemen specifically as it has almost always been difficult to understand from the outside. Yemen, labelled by the Romans as Arabia Felix – “Happy Arabia” – thanks to its bountiful agriculture and trade wealth, is known to the modern world primarily as a country stricken by war, famine, and unrelenting civil strife, has never attracted the attention garnered by other countries of the Arab world and has often suffered from marginalisation and misunderstanding borne of superficial and fleeting glimpses captured by outsiders content not to look beyond the obvious. I wanted to try to understand more of Yemen, firstly for myself, and then beyond as a means to sharing the richness and beauty of Yemeni culture with others.

The conflict is an inescapable aspect of life in Yemen at present and has dominated the vast majority of international attention and coverage of the country. From discussions with Yemeni friends while living alongside Yemeni communities in Egypt and Oman, I realised that, although reportage does allow important stories and messages to be shared, it frequently perpetuates this history of marginalisation by maintaining a top-down view of Yemenis as victims stuck without agency in dire circumstances. I wanted to offer something different, a view of a place amidst my growing understanding developed through personal relationships and travel within the country. I hope that, in some way, my photographs are able to share some of this ongoing process of seeking to understand and connect.

Although reportage does allow important stories and messages to be shared, it frequently perpetuates this history of marginalisation by maintaining a top-down view of Yemenis as victims stuck without agency in dire circumstances.

I have been lucky enough to be granted access to many areas of the country during successive visits, including areas controlled by the Houthis in North Yemen and their seat of government, Sana’a. There is simply nowhere in the world like Sana’a, especially the historic heart of the city, and I was naturally drawn to its unique architectural beauty and the daily lives of its inhabitants. Having studied Sana’ani Arabic and with several close friends living there, I feel quite an intense emotional connection to the city, and it was a privilege to be able to walk its streets and express that connection through my photographs.

Іншим місцем, яке я був дуже радий побачити на власні очі та спробувати зафіксувати на плівку, була система долин регіону Хадрамауті з її запиленими селами, розташованими серед сяючих скель. Зокрема, село Хаїд-аль-Джазіль вражає особливо, оскільки воно знаходиться на вершині валуна, що височіє над долиною, — так поселення завжди було захищене від ворожих набігів і повеней. Крім того, мене цікавила архітектура Хадрамаута, а саме хмарочоси у місті Шибам.

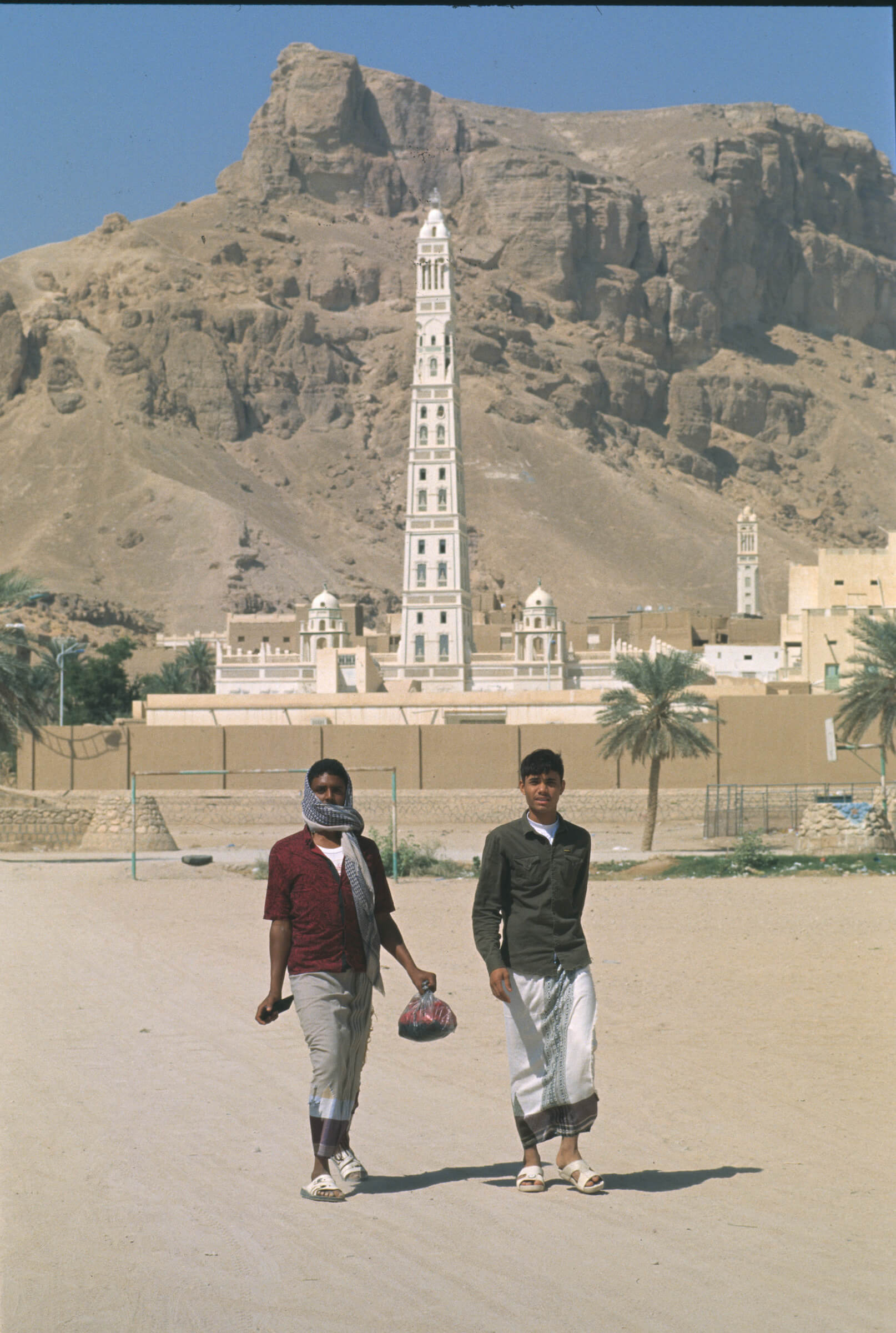

Another area I was especially delighted to see with my own eyes and try and express on film was the central valley system in Hadhramaut, with its mud-baked villages perched elegantly amidst the shining cliffs of the Jawl, the Hadhramaut plateau. One village in particular, Haid al-Jazil, is renowned as being particularly striking, as it sits entirely atop a boulder that soars above the valley floor, protecting the village from floods or, historically, from raids. The historic skyscrapers of Shibam, also in Hadhramaut, are another wonder of the architectural world.

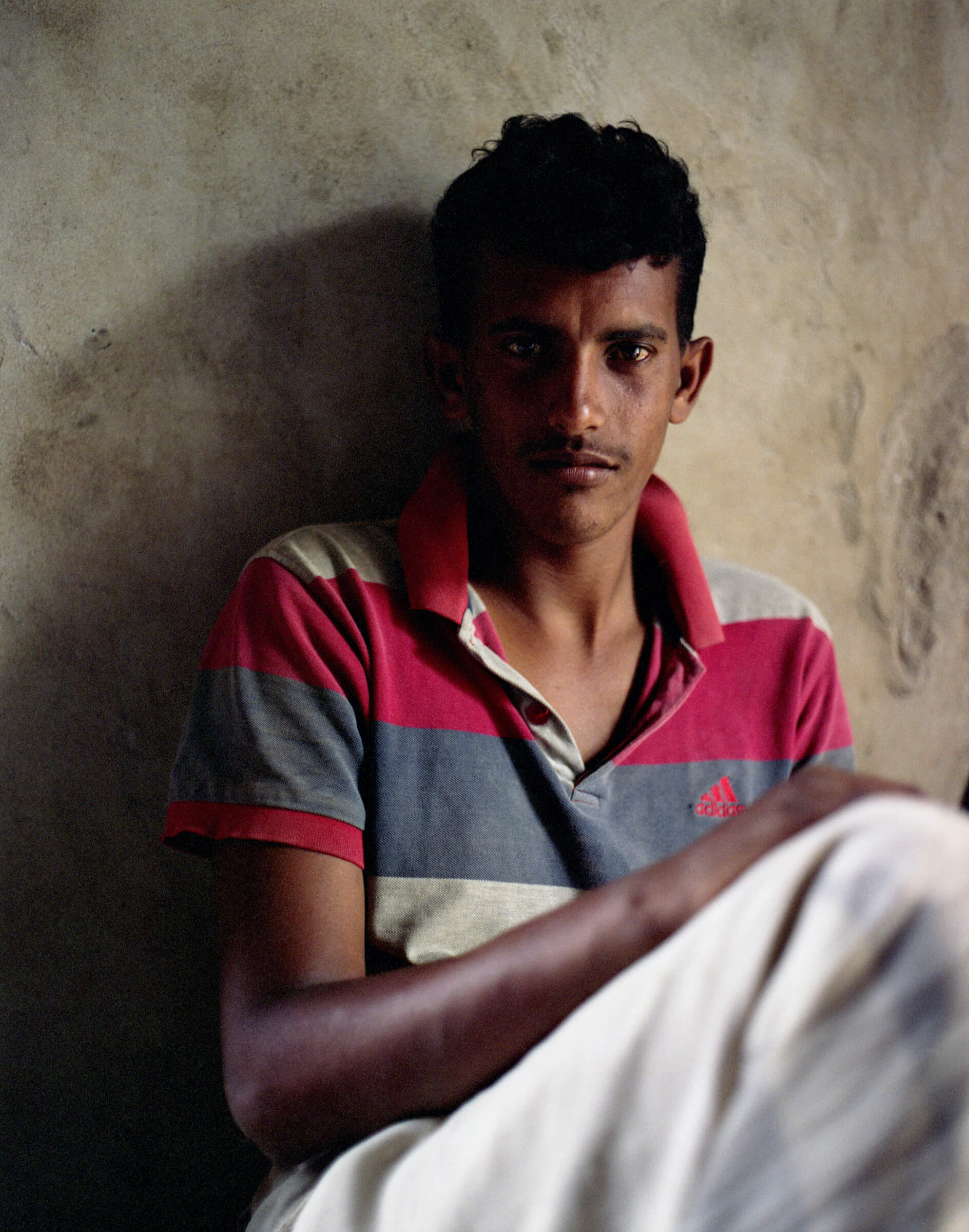

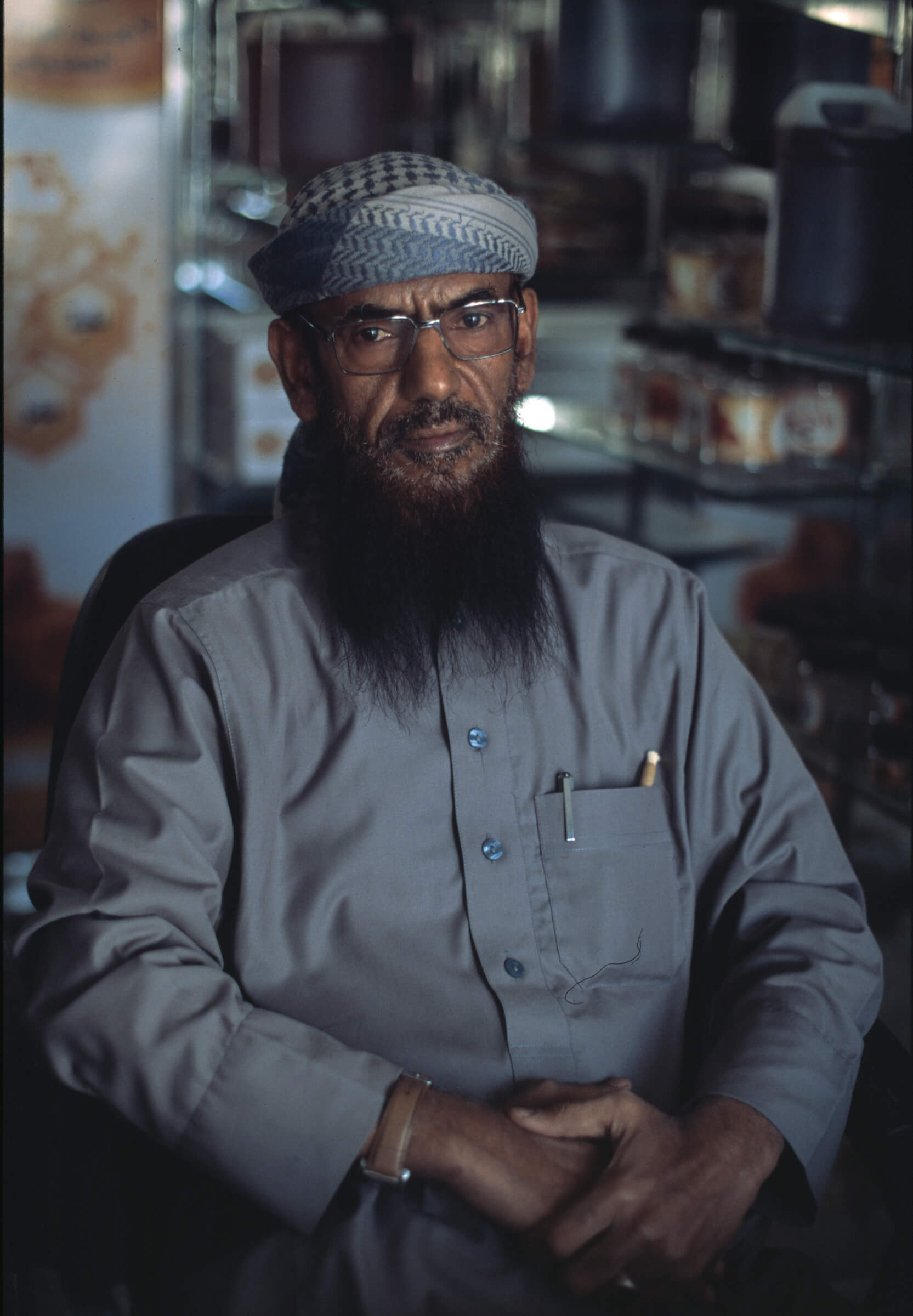

The people I’ve encountered have been very keen to be seen, which in many ways felt like a validation of my aims in putting the project together. I wanted my subjects to be seen on their own terms, and as such, the conversations surrounding each photograph are as important and precious in my own memory as the images themselves. I tried to photograph anybody that wanted to be photographed. They are everyday people on the street, in their workplaces, sometimes in their homes, at rest, at leisure, at work. There was no specific subject profile that I sought out while taking portraits – I simply wanted to see as much as I could.

The one area, however, that it would not be proper for me to photograph is the daily life of women. Yemeni culture is broadly conservative and remains rooted in tradition, and as a male photographer, it was rare to find opportunities where women were comfortable with my camera. My view is that it is simply not my place to share those stories, and as such, I do not feel that FELIX is poorer for lacking female portraits – it is merely an expression of what I have been able to see and does not (and should not) attempt to encapsulate the whole of Yemen. There are many remarkable and extremely talented Yemeni female photographers, such as Hayat al-Sharif and Yumna al-Arashi, whose work tells women’s stories, and those of Yemen as a whole, much more ably than mine.

The one area, however, that it would not be proper for me to photograph is the daily life of women.

The goal of the project is simple: I wanted to show viewers who only really experience Yemen through traditional conflict photography and photojournalism the Yemen I have been privileged enough to see: the rhythms of its daily life, its rich heritage and traditions, smiles and laughter amidst the ongoing pain of conflict. In short: that life goes on.

I must admit that I’m biased, as I love Yemen and its people and hope for better than what the country currently endures. This bias is probably evident in my photographs, but I don’t view that as a disadvantage: I hope that the primary impact will be to share some of that love and perhaps inspire others to seek to understand Yemenis and their culture beyond the headlines.

I plan to keep visiting Yemen as long as it remains possible to do so, and there are places I would very much like to include in a final draft if FELIX does make it to book form: I would love to explore the historical capitals of Zabid and Jibla. For now, however, I am content to let the project grow in its own time.

New and best