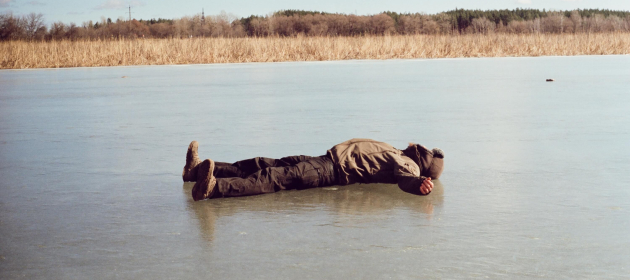

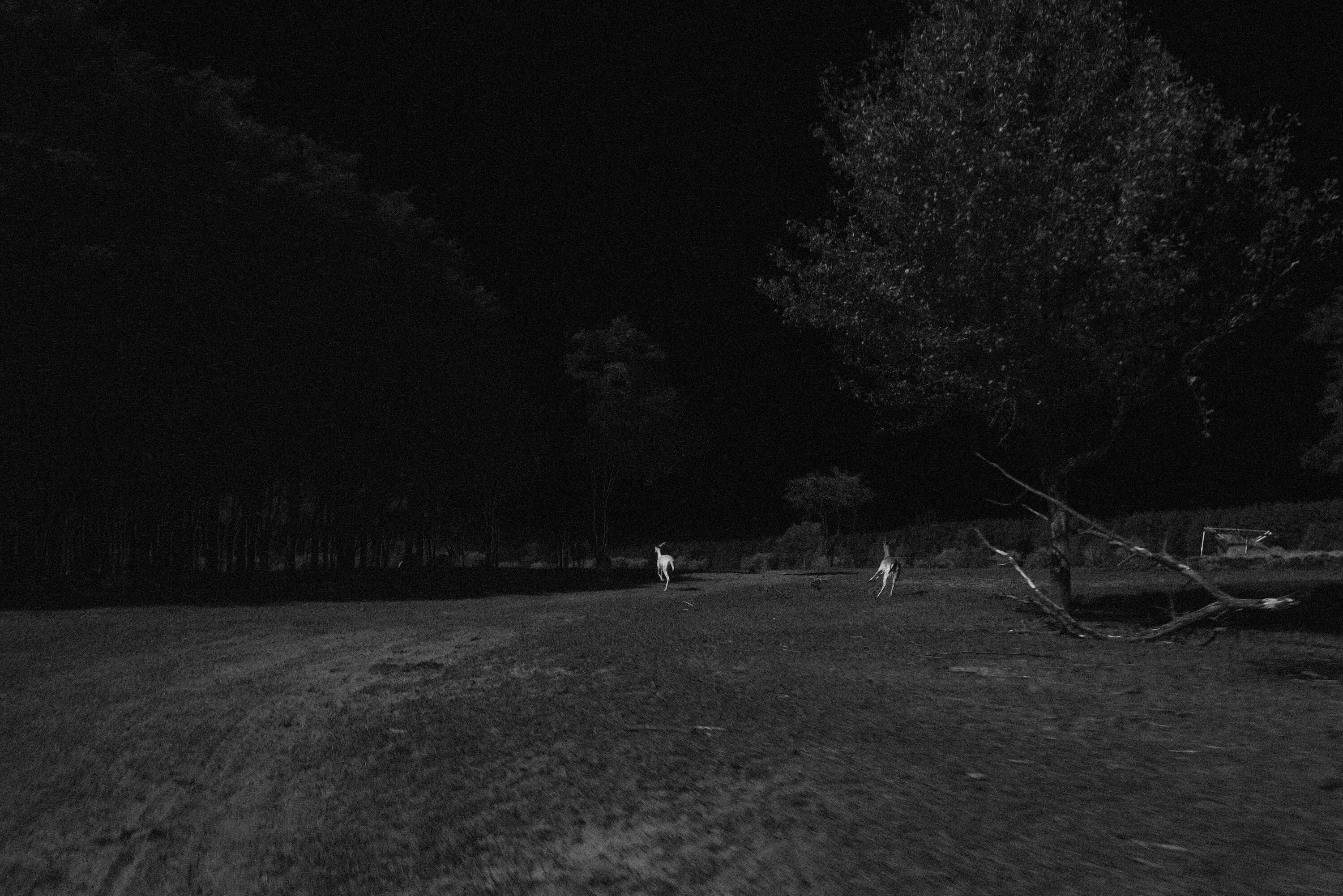

Survival Struggle: Threats to Wild Animals in Ukraine

According to experts’ estimates, currently, about a third of Ukraine’s territory is mined. And not only humans but also animals can perish from these explosive devices, as well as from missiles and bullets. Apart from these direct consequences of armed conflicts, there are indirect ones too—fires that are not always easy to extinguish, contamination of water, soil, and air, poaching.

Even after wars end, nature continues to feel their impact: people become poorer, land protection weakens, populations of species that form the diet of predatory animals decrease, barriers emerge at borders, and there isn’t enough time and resources for monitoring, protecting, and researching natural ecosystems. We delve into what usually happens to wild animals during armed conflicts and how they are surviving the current war in Ukraine.

Wild animals are in danger

From 1950 to 2000, 80% of wars occurred in so-called hotspots — geographic areas with high biodiversity. Rich in natural resources, these territories often become the focus of geopolitical interests. The impact of armed conflict on fauna was expectedly negative, although not always direct.

There are few long-term quality studies on this topic because it is too dangerous and expensive to conduct research in conflict zones. However, such studies do exist. One such study was published in the journal Nature and focused on Africa. Military conflicts there are ongoing and have both positive and negative effects on wildlife. The positive aspect involves the official ban on hunting. The negative aspect involves the proliferation of poaching, one of the sources of funding for military groups on the African continent. So, which outweighs the other — harm or benefit?

In response to this question, researchers Josh Daskin from Yale and Robert Pringle from Princeton University analyzed data collected from 1946 to 2010. They investigated 250 populations of 36 species of large herbivorous mammals, such as elephants, antelopes, hippos, rhinos, and giraffes (important species for predators and ecosystems in general), in 126 protected areas across the entire African continent. The researchers found that over 70% of the parks in these areas were affected by armed conflicts. They also determined that the main factor affecting wildlife populations is the frequency of military conflicts, not their intensity.

For example, in Mozambique, where from the mid-1960s to the 1990s there were continuous local battles—first for independence and then a civil war—large mammal populations in the Gorongosa National Park were practically annihilated. Subsequent military clashes in the country led to an over 80% decrease in the elephant population by the early 2000s, and populations of buffaloes, hippos, various antelopes, and zebras dwindled to tens or even units.

The end of military actions doesn’t signify the restoration of fauna. The consequences of the Vietnam War, which lasted sixteen years and ended in 1975, are still visible. The country, which is half the size of Ukraine, was saturated with various agents of war. During the full-scale U.S. military involvement, 74 million liters of herbicides were sprayed over Vietnam (the chemicals were meant to destroy tropical forests where the camps of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam soldiers were located, leaving them without cover), along with 400 thousand tons of napalm and up to 6.2 million tons of bombs and mines.

The consequences of the Vietnam War, which lasted sixteen years and ended in 1975, are still visible.

By spraying defoliants—chemical compounds that cause plant leaves to fall off, primarily along rivers—Americans caused damage to plants on land and in wetland areas. Settling into the soil, these compounds entered the food chain of animals. Even today, half a century after the end of the conflict, scientists are finding dioxins, harmful derivatives of defoliants, in the tissues of animals and humans. However, the most significant damage was inflicted on Asian black bears and Malayan sun bears, animals that inhabit the forests of Vietnam. These species spend a significant part of their lives in trees, feeding on leaves among other things.

Today, these animals are easier to find on “bear farms” or in bear sanctuaries than in the wild. Bears are not the only ones affected. Due to the reduction in the food chain, poaching, and the threat of landmines, only five tigers are left in the wild in Vietnam.

Three years ago, photos of Yemeni poachers posing with killed animals went viral on the internet. According to conservation organizations, within just seven months of 2020, they killed 34 rare animals, including caracals and wolves. Between 2015 and 2019, poachers in Yemen also destroyed 31 Arabian leopards, a subspecies that is critically endangered, with only a few hundred individuals remaining worldwide. In Afghanistan, bears, caracals, and cheetahs are also under threat of extinction due to illegal hunting.

Divided by walls

Animals don’t know borders, but they are forced to depend on them too. Migration crises, provoked by Russia and Belarus, have led European countries to build walls. According to recent estimates, the total length of border fences in Eurasia alone (excluding the Middle East) reaches 30,000 kilometers.

These walls negatively impact animal populations, as certain groups become divided and isolated.

Recently, scientists conducted a study using GPS to track deer living on both sides of the border between Germany and the Czech Republic. It was discovered that even 25 years after the complete removal of electrified border fences between the countries, deer still do not cross this boundary. Although none of the living deer have ever seen such a barrier—they typically don’t live longer than 15 years—it seems that mother deer still teach their fawns not to cross the border due to the danger.

Even 25 years after the complete disappearance of electrified border fences between the countries, deer still do not overcome this boundary.

Meanwhile, new barriers made of barbed wire, like the ones installed by Slovenia along the border with Croatia, are emerging. They further divide transborder Dinaric-Balkan populations of wolves, lynxes, and brown bears, which already suffer due to isolation.

The border barrier crossing the territory of the Białowieża Forest also makes it impossible for bears to migrate and separates wolf packs and lynx families. This, again, threatens the genetic diversity and endangers animals attempting to cross this border. There have already been cases of bison deaths, as documented here.

In many countries, there is ample evidence of the demise of both small and large animals due to border barriers: they get entangled in wires, crash into fences, step on mines, or get electrocuted. Over the past three years, the Australian Wildlife Hospital treated over 80 different species of animals found caught on barbed wire fences. Out of more than 800 animals, half had to be euthanized due to injuries. Additionally, these fences and crossings (whether created by humans or animals) are utilized as traps by poachers.

In Kashmir, the number of attacks by Himalayan bears and leopards on humans has increased due to border fences, hindering animals from freely moving and seeking their usual prey.

Borders with Russia and Belarus are already perilous for animals due to constant military presence and landmines. Furthermore, it complicates the access for forest rangers and scientists. Bears accustomed to living in these territories are now forced to migrate. For example, in the interfluve between the Dnieper and Desna rivers, bears hadn’t been seen for decades, but they appeared there in 2023.

Even in the relatively peaceful Carpathian region, if neighboring countries start building serious barriers, the bear population will be at risk. Without young bears from Slovakia, Romania, and Poland, our group stands little chance.

In the interfluve between the Dnieper and Desna rivers, bears hadn’t been seen for decades, but they appeared there in 2023.

Only in specific cases do barriers somewhat improve the state of ecosystems by reducing human presence and poaching. For example, such an effect is observed in the uninhabited demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. However, this usually applies to specific animal species, such as birds of prey or small primates.

Who does the war feed

The fact that the wolf is a ‘war animal’ has been talked about since medieval times. Once, humans were a part of its diet, and not necessarily alive. So, epidemics, wars, and famine – all of these feed the wolf. The same happens now because predators usually don’t pass by an additional source of protein – the bodies of the deceased. But not only that has made life easier for canids. For wolves, foxes, and jackals, stopping hunting in areas with military actions and the halt in gathering harvests in fields are significant. The grain left behind becomes food for rodents. Rodents are food for canids, just like abandoned domestic dogs and cats.

This might be a temporary effect because waves of rodent populations don’t last forever. And predators, in general, aren’t the types that become massive and stay that way. However, at a certain time, the population can indeed increase significantly. For example, the number of wolves throughout Ukraine increased during the wartime from 1914 to the 1920s. In 1927-1928, wolves even appeared in Crimea, although it was believed that the last individual there was hunted down in 1924. But after the intensified struggle against the predator, its population decreased again. The next surge in wolf reproduction was observed during the Second World War when the fight against these animals significantly weakened again, and wartime actions provided them with easy food. In 1947-1949, there were about 7,000 individuals – the highest number in the entire history of counting on the territory of Ukraine. Such a spread of the predator creates additional risks for the situation with rabies and vulnerable prey species, such as hares or deer.

In 1947-1949, there were about 7,000 wolves – this was the highest number recorded in the entire history of counting in the territory of Ukraine.

Wolves, foxes, jackals, and also mustelids (badgers, polecats) are not very afraid of humans or machinery. For them, especially for young animals, military positions can be a source of food and simple curiosity. Hence the dozens of videos with fox cubs or polecats in trenches, and so on.

Wojtek the Bear is one of the most famous “war animals” in the world. He was officially enlisted in the register of the 22nd Artillery Supply Company of the Second Polish Corps, which traveled through Iran, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Italy, and spent his retirement in Great Britain. Keeping wild animals as mascots is still popular. We have seen a wolf from our 1st OMB of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, “Wolves of Vinci” (currently transferred to a shelter), those same polecats or fox cubs at the positions of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in Tikhotokha, and a raccoon dog stolen by the occupiers from the Kherson zoo.

During the full-scale invasion, even the usual flow of smuggling wild animal cubs and other wildlife froze. Borders and ports, airports are now inconvenient for such trafficking. However, this is a business capable of quickly recovering. Ukraine is a transit zone with almost no control between Asia and Europe. And this is an ideal environment for conditionally legal (thanks to loopholes in legislation) and illegal transportation of wild animals across our borders – both those caught in the wild and those bred in captivity for this purpose.

There is another subtle aspect of the war’s impact on wildlife – the active use of training military grounds. Wolves in Germany were once completely eradicated and have recently started returning primarily to military training grounds rather than conservation areas. In our regional landscape park “Mizhrichynsky” in Chernihiv region, there are also military training grounds. They were not used very actively; instead, there were fewer attempts of poaching or transportation, which concerned the animals. So before the invasion, these grounds served as islands of tranquility for lynx and wolves, but obviously not anymore.

Wolves in Germany were once completely exterminated and have recently started returning, primarily to military training grounds.

However, overall, wolves, jackals, and foxes will likely endure even under the most negative scenarios of war development. The most vulnerable species are still the brown bear and lynx. But aside from the large predators, there are dozens of animal species that could be lost soon. For instance, the steppe mouse-hamster is under threat due to dam destruction, overgrazing, and its tiny habitat in Ukraine falling within the conflict zone, among other factors.

In total, one-third of Ukraine’s natural reserve fund has been affected, with some losses being irreversible. It will take years just to assess the damages. Ukraine might receive billions in compensation, but it’s unlikely to recover everything that will be destroyed.

Photo: Yelyzaveta Bukreyeva, exclusively for Bird in Flight

This material was created as part of the “Life in War” project with the support of the NGO “Laboratory of Public Interest Journalism” and the Documenting Ukraine project at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. (Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen, IWM).

New and best