“We Think You’re a Woman. You’ll Like This Swimsuit”

Whenever you visit a website these days, chances are, you’re gonna be asked for permission to use cookies: some resources even go as far as being inaccessible without them. Cookies store user data, from language settings and saved passwords to the history of user behavior on other websites. One might think that technology lets online stores, social media, and magazines know pretty much everything about us, but in truth, it’s not (yet) entirely so.

Photographer and art director from Sevastopol. Covered armed conflicts in Georgia, Afghanistan, and Israel. Has collaborated with The New York Times, Time Magazine, Financial Times, Vogue, and GQ. Has his own projects, such as a children’s book called “Cosmos.” Lives in Paris and is engaged in the new MA program of the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague.

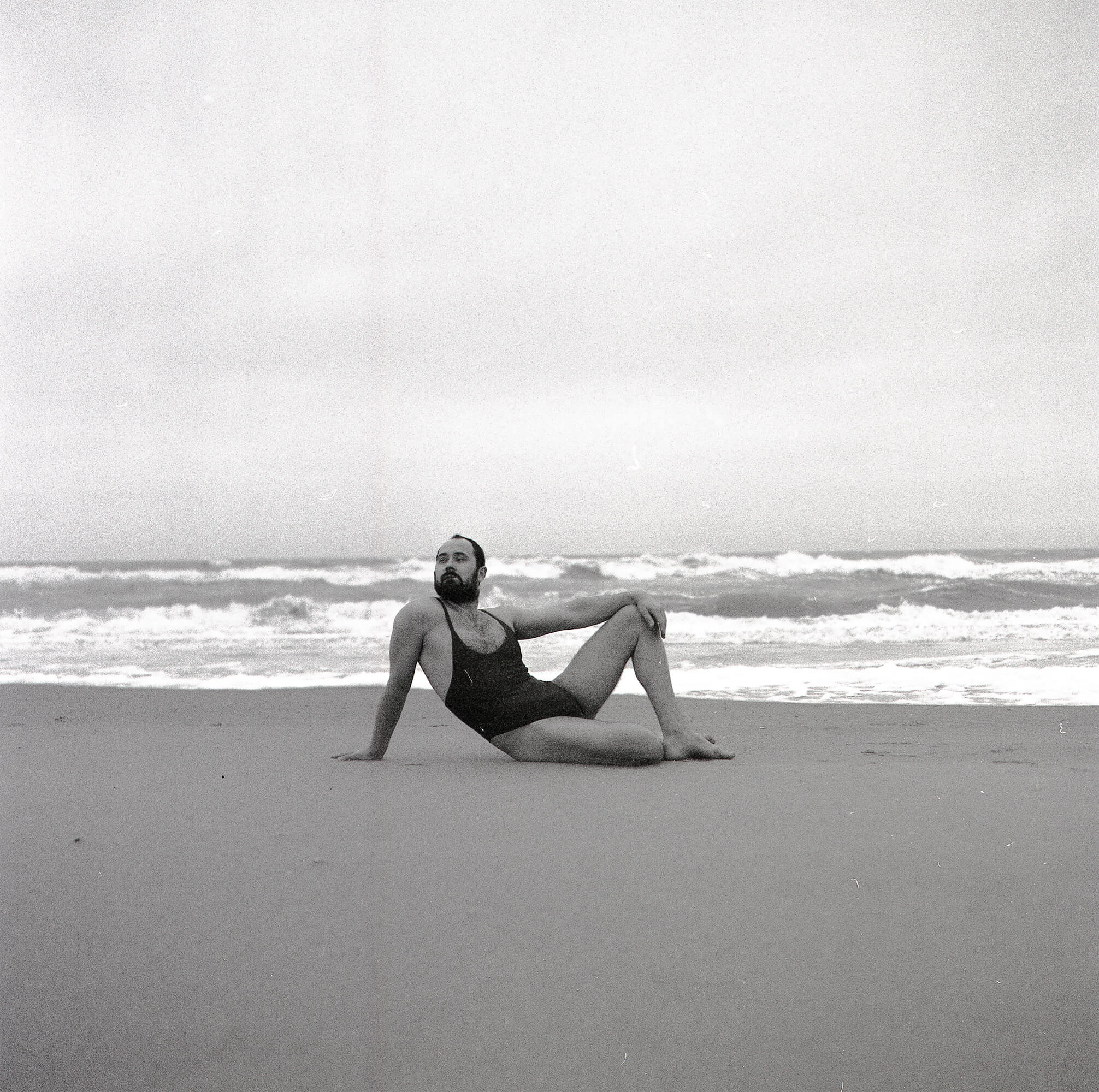

— My computer thinks I’m a woman.

I came to this realization through all kinds of details. Sometimes I get emails starting with, “Dear Mademoiselle Dmytro Kostiukov, thank you for your purchase…” Some online stores may automatically redirect me to the women’s clothing page. Google may translate some texts from English using the feminine gender.

For a long time, I would notice quite a lot of such slips but never went further than just having a laugh with my friends about it. Then, one day, I got a collaboration offer where they asked me to become a model and an ambassador of a women’s swimsuit manufacturer. Its founder was a woman from Northern Europe, and they only had women’s clothing. The brand is super woke and celebrates diversity in its model shots.

I have never concealed the fact that I was a man, nor hidden my name on social media. The letter even said the company liked my Instagram. I still don’t know whether there was a human or a robot behind it. Long story short, I accepted the offer and, under the nickname Bright_Woman, became a brand ambassador in January.

For my first swimsuit, I was recommended a Bora Bora bikini or a Scarlett one-piece. I chose the latter, especially considering the bikini was in high demand and I had to wait for it a long time. I received an (undoubtedly automatic) email with congratulations from the company owner, a 15%-off promo code for my friends, and a red swimsuit. I was thrilled.

I went to a beach that was the closest, in The Hague. Under a steady rain, at seven degrees Celsius, which felt like zero because of the stormy wind, and with the brand’s Instagram and beach photos as a reference, I combined reality (the first photo) with the algorithm’s vision (the rest of them).

I don’t know what will come out of it yet. I posted the photos, wrote to the manager, and am now waiting for a reply. Some people wrote to me saying the algorithm misgenders them too. Others praised my ad and asked for the discount code. Several men took photos in swimsuits, excited to learn they could actually do it.

Naturally, I know that such mass mailing campaigns are a way to sell products, but besides that, they also show how the algorithm sees us. Apparently, it sees me as an average-height, 82-kilogram woman who reads feminist articles from time to time and has 10 thousand followers on Instagram. That’s exactly what some brands need.

Apparently, I am an average-height, 82-kilogram woman.

But is it really me? The story I’ve just told you implies I am going to have myself a beach holiday. Although, if the algorithm knew me a bit better, it would have known I never go on beach vacations. I am not even sure I own swim trunks.

Well, at least I am now an owner of at least one swimsuit.

New and best