The Most Uninteresting in Color: Saul Leiter, the Master of Street Photography

Saul Leiter was born in Pittsburgh to a rabbi who was an author of numerous religious articles and books. Relatives were sure that he would follow in his father’s footsteps. “We live in a world full of expectations. And if you have the courage, you ignore the expectations,” argued the photographer, who, instead of studying the Talmud, chose a bohemian life. So, in 1946, Leiter dropped out of the theological college in Cleveland and moved to New York. In the 40s, the city was a Mecca of new art for young talented people.

In the same 1946, Leiter met the abstractionist Richard Pousette-Dart and the photographer Eugene Smith, who pushed him to take photographs. The following year, Leiter visited an exhibition of another classic of photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson, at the Museum of Modern Art, which only confirmed his choice. Saul began filming with a camera that Smith gave him, and his love of abstract painting initially shaped his style. “And so I started taking pictures,” he said, “and I thought, ‘well, maybe this could lead to something.’”

The art curator Jane Livingston, in an introductory essay to “The New York School: Photographs, 1936-1963,” noted that “the presence in New York of the editorial offices of a new breed of picture magazine also shaped the city’s cultural climate and made environment for photography distinctly different and more fertile than those found in Chicago or on the West Coast – Jane Livingstone “New York School Photographs 1936-1963.”

Saul Leiter took advantage of this situation and began working as an assistant to Henry Wolf, art director of Harper’s Bazaar, in the 1950s. He also shot for Esquire and Vogue, and his works dominated magazine pages for a decade. Together with other photographers such as Richard Avedon and Hiro, Leiter created a new advertising language.

The sixties were the pinnacle of creative freedom in fashion photography, but that changed over the next decade. Later on, Leiter said: “I found behind my back the leaders, their assistants and even the assistants of the assistants, who taught how and what to shoot.”

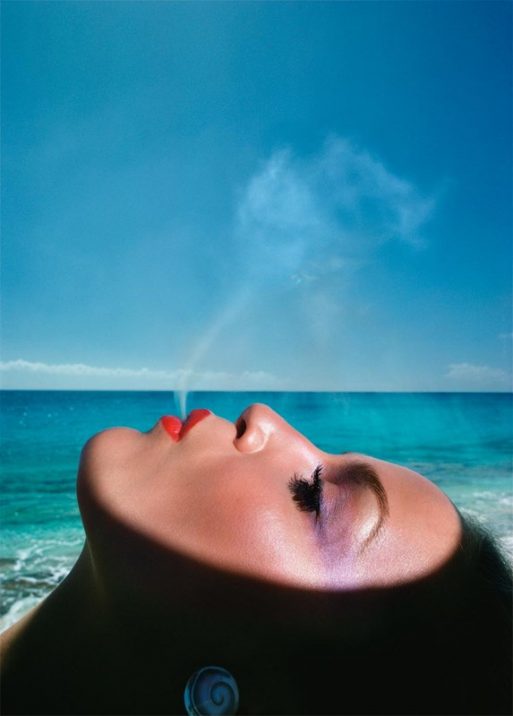

Nudity

He decided to leave commercial photography, thus gaining freedom, and his photographs immediately became more intimate, softer. The famous female nude series “In My Room,” created in Leiter’s workshop, can serve as his manifesto for creative freedom.

“Leiter’s nudes have a spontaneous and romantic quality, like the scattered pages of a diary or stills from early movies. These women are completely natural in front of Leiter’s camera and uninhibited. They are waking up, taking a bath, applying lipstick or makeup, smoking the first cigarette of the day. One is pensively holding a cup of coffee, another still has rollers in her hair, her face creased by the pillow; one is rolling down her black stockings, another is lying on the floor against a background of slightly out-of-focus and crumpled newspaper sheets. They are dressing, undressing, pulling a skirt’s zipper, unbuttoning a blouse, or simply daydreaming. Leiter photographs two women in bed together, one dressed in a man’s shirt, the other in a feminine negligee… ”- this is how photography historian Karol Naggar described his pictures.

The famous female nude series “In My Room,” created in Leiter’s workshop, can serve as his manifesto for creative freedom.

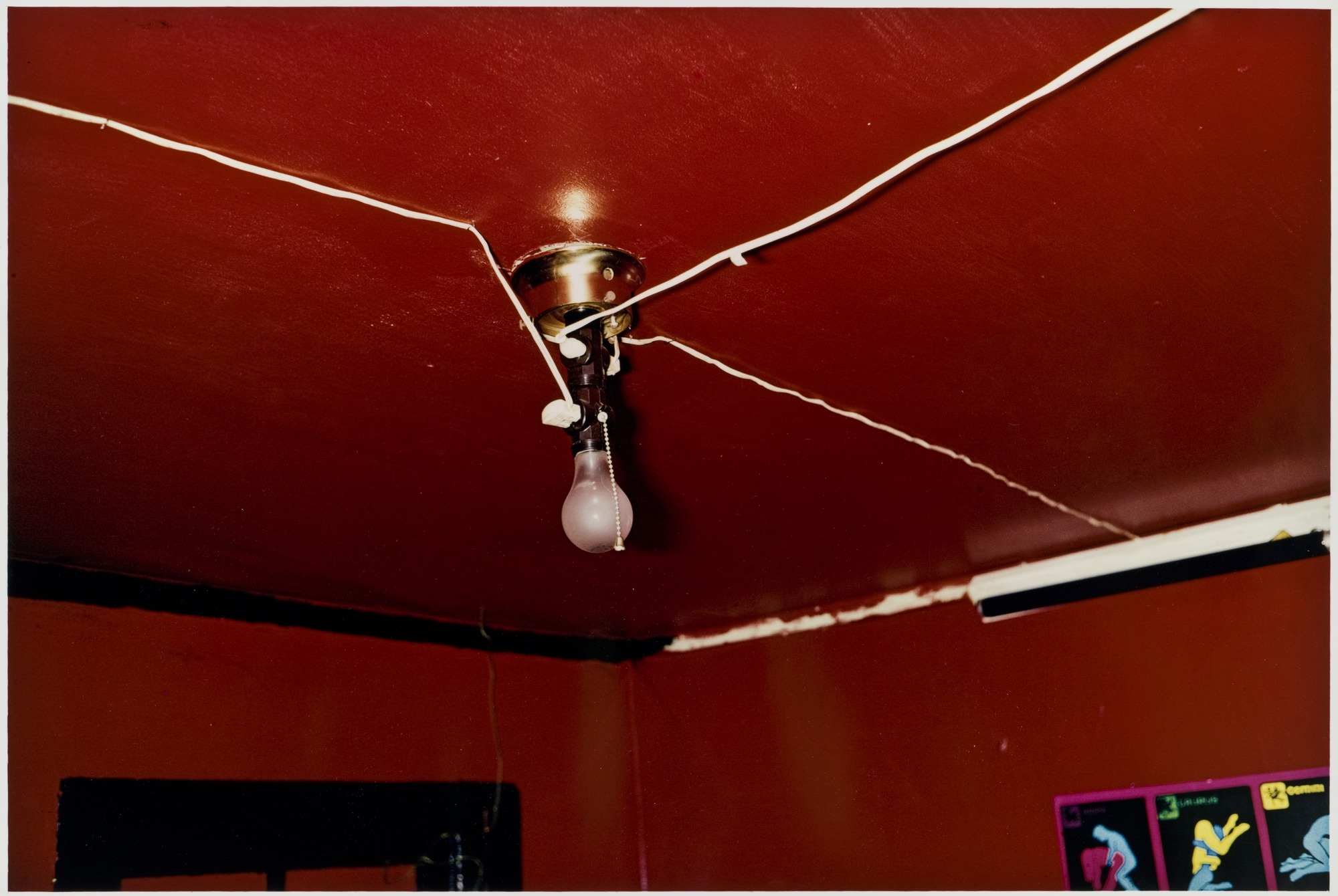

Leiter’s apartment on East 10th Street, with diffused light and almost Buddhist emptiness, is also an essential part of this intimate series in black and white. The fact is that, while Leiter had his color film processed by photo labs in New York, he developed the black and white nudes himself in his own darkroom, which saved the master from censorship and problems with the law.

Color

In the 50s, little was still filmed in color, but Leiter did it on his own – he went out and photographed the life around him. Saul’s works, which he didn’t show to anyone at first, are characterized by his keen eye for detail and a sense of lightness. He was not afraid to fragment the world around him, finding extraordinary beauty in small moments of everyday life. Here is his, at first glance, simple philosophy: “I think when you take a photograph, if it turns out to be something good, there’s a kind of Zen element that takes place. It’s difficult to describe. People talk of controlling, but it’s not true. You can’t control the swirl of reality. If you’re very lucky, from time to time, you do something that is good.”

Sometimes, he applied paint strokes to the film or colored the already printed pictures, creating a kind of abstraction.

Leiter concentrated not on the plot but on the poetry of what was happening around him. Due to the high cost of the material, Saul often used expired film, which contributed to the unpredictability of the color shifts. Though, even without manipulating colors, he brought photography close to painting using various techniques. He found atypical angles, often shot through something to give a different look or used reflection. Sometimes Leiter blurred the main objects, focusing on the details instead.

Leiter concentrated on the poetry of what was happening around him. Though, even without manipulating colors, he brought photography close to painting.

He was a prominent representative of the New York School of Photography. Bold experimentation, democracy, aestheticism – these are significant traits shared by the masters of this style. The work of Cartier-Bresson and his idea that you need minimal means to obtain maximum effect – was the cornerstone for many of Leiter’s contemporaries. After all, Cartier-Bresson himself only used one “Leica” to create his worlds.

Another technique Leiter borrowed from Picasso. As the Spanish painter once said, “If I don’t have red, I use blue.” Likewise, Leiter challenged himself by sometimes using unsuitable lenses. Finally, the photographer’s love for vertical format stems from Japanese fine art, of which Saul was also a big admirer.

The worldview of mid-twentieth-century photographers was, as well, shaped by the work of Lewis Hine and Walker Evans; Leiter learned a lot from these masters. Curiosity, hard work, a desire to be ahead of time, and establishing photography as the most important of the arts – all of them are gifts from the previous generation of authors. But color photography allowed Leiter to see the world in a way that was uniquely his own.

“There are many beautiful things around us, and people have a way and a talent for not noticing it because they’re lazy and because they’re spoiled,” he said. Sol believed that “the most uninteresting thing can be very interesting.”

Leiter’s photographs reflect the elusive moments of our existence. They are like colored pieces of glass that make up the mosaics of everyday life. Leiter’s viewer, examining the work of the master, participates in the act of reconstructing the complete picture of the world. Without knowing it, Leiter’s viewer is changed forever.

New and best